Chapter And Authors Information

Content

Abstract

This study extends our earlier and recent research on the quality of life (QOL) and quality of working life (QWL). Based on the literature review and the survey conducted in Lithuania’s private and public sectors, we redefine the concepts of QOL and QWL and develop a model that could help assess QOL and QWL in an organization. The aim of this study is to put in highlights the paradigm shifts in QOL management and to generalize research in this area. Research results reveal and confirm that the QOL and QWL can be measured, improved, and managed. Furthermore, an organization can increase employees’ QOL and QWL. And even more – a higher level of QWL is also associated with increased QOL, happiness, life satisfaction, and subjective well-being. The authors also performed benchmarking of QOL in countries and cities of the world and research conducted in Lithuania that revealed differences in assessments of QOL and QWL across public and private sector employees.

Keywords

Management, Quality of Life, Quality of Working Life, Balance of Work and Personal Life, Model

Introduction

Stemming from the disciplines of economics, sociology, and politology, this concept of the QOL originated in Western Europe in the mid of 20th century as a result of improving the economy and shifting needs (e.g., decreased materialistic interest) of the society. The concept of QOL comes into conflict with the exceptional profits of monopolies and their reckless accumulation. Development sustainability (i.e., the methods used to ensure the development of individuals in the present while preserving it in the future) also refers to the QOL. The idea is to alleviate poverty, set a life project significant (in terms of QOL), satisfy the main needs of individuals, stimulate economic growth and political development, and prevent the deterioration of natural resources. We find, in the ancient myths, religions, and philosophies, this quest for QOL. Ancient Greek philosophers searched for meaning in life and principles that would help achieve a better living standard. The philosophers sought ways to enhance life’s meaning and achieve a higher existence level. For example, the concept of the “good life” has been discussed by Plato and Aristotle. While both philosophers touched on this concept, their definitions of the “good life” differed. Within this context, the highest value for Plato has logically based contemplation, which was deemed superior to feelings. Aristotle, on the other hand, declared that life without feelings, even if it involved risk was useless. It is important to note, that the modern health concepts are based on the views of these two prominent philosophers: “Health is not the absence of a disease but absolute physical, psychological and social well-being” (this reminds Plato) and other modern theories claim that risk and stress are natural parts of life. This theory resembles Aristotle’s concept of the “good life” (Akranavičiūtė & Ruževičius, 2007; Susnienė & Jurkauskas, 2009).

Undoubtedly, QOL and QWL are important and constantly evolving concepts and methodological constructs. In recent years, both QOL and QWL are becoming increasingly popular concepts, so not surprising that many articles can be found on these topics, which shows their growing relevance. The consensus is that the QWL is strongly related to the QOL and vice versa. The ability to work remotely or anywhere you want causes a problem: employees cannot draw the line between their work time or tasks and their leisure. So, the idea that job tasks are accessible anytime and everywhere, caused a lot of damage to people’s QWL and QOL. To be more precise – to the QOL and QWL balance. Various criteria are currently used (e.g., health, family, leisure, financial situation, etc.), helping to develop the QOL and QWL assessment indicator systems. There is various QOL assessment systems and indicators have been developed: the M. D. Morris index, Ferrans, and Powers QOL indicator, Human Social Development Index, the European QOL study, The Economist Intelligence Unit QOL indicator, and the Mercer Human Research QOL assessment. New QOL indicators for QOL and to assess the quality of ecological life in the cities and countries of the world (Numbeo, 2023; Mercer, 2007, 2012, 2020; Ruževičius, 2007, 2010, 2012, 2014; Ruževičius, J & Ivanova, 2019; Ruževičius, J. & Valiukaitė, 2017).

The purpose of the chapter is to summarize the latest results of the author’s research in the field of QOL. The results of the research carried out in 2005 – 2023 were first published in the article (Akranavičiūtė & Ruževičius, 2007). This article is one of the most read by scientists in the world – until April 2023, it was read by over 88,500 ResearchGate.net readers. Referring to our continuous systematic research, measures of work environment correction actions were prepared and implemented in the organization. After a few years, at the start of 2007, then 2014 and 2023, the authors provide insights into QWL and QWL potential improvement actions and the effectiveness and efficiency of measures to improve them.

The Factors, Dimensions, and the Model of Quality of Life

The QOL has attracted research interest for more than seven decades and a comprehensive definition that reflects its multifaceted nature exists to date. Now the WHO (World Health Organization) has expanded the definition from health to the notion of physical, psychological, and social well-being. WHO defines QOL as a system shaped by the culture and scale values of individuals. It determines their way of life, their relationships, their goals, their hopes, their requirements in life, and their general interests (WHOQOL…, 2023). It is a broad concept that encompasses the psychological and physical health of an individual, his degree of independence, his social connections, and the nature of his relationship with those around him. According to the WHO, QOL is “an individual’s perception of their place in life, within the context of culture and of the system of values in which he lives, concerning his objectives, his expectations, their standards, and concerns”. It is a broad conceptual field, encompassing complex ways the person’s physical health, psychological state, level of independence, social relationships, personal beliefs, and relationship with the specificities of their environment. Consequently, the concept of QOL encompasses the factors in an individual’s life. QOL depends on internal and external factors. Furthermore, it can be defined as how satisfied one is with the aspects of their lives, including their physical and mental health and their independence, as well as social interaction with others and their environment.

Afterward, we witness a modification in the concepts of life and values. It does not go well without influencing the conception of the QOL and all the changes of factors. Assessing the QOL requires taking into consideration all these settings. QOL is also a term used to measure welfare. This notion describes what people think of their environment, and all of these perceptions can represent the QOL. The study on the QOL covers a very wide range of policy areas while responding to a particular need to locate and understand disparities associated with age, gender, health, income, social class, and region. The vagueness which surrounds this concept is systematically underlined by the authors who were interested in it. However, researchers agree that the QOL is a multidimensional concept (Ruževičius, 2007, 2012, 2014; Ruževičius & Ivanova, 2019).

The main problem lies in the absence of a universal criterion of QOL. The QOL depends on the mental and physical health of individuals, their degree of independence, their social relationship with the environment, and other factors, so it means that QOL can be linked to the adequacy that an individual experiences between his everyday life and his ideal of life. The evaluation of the QOL depends on the value system of individuals and the cultural environment in which they live. To measure and compare the QOL of individuals in several countries indicators are used in general that evaluates economic, socio-cultural, and environmental aspects of politics, health services, education, transport, geographical conditions, the public sector, and also suppliers of products and services (Hassan et al., 2014; Merkys et al., 2008; Ruževičius, 2007, 2012, 2014; Ruževičius & Ivanova, 2019; Susnienė & Jurkauskas, 2009). Below are the main nine indicators, ranked by importance, that define the QOL:

- health;

- material comfort (according to GNP);

- security and political stability;

- family life;

- social life;

- climatic and geographical location;

- employment rate;

- political freedom;

- gender equality, etc.

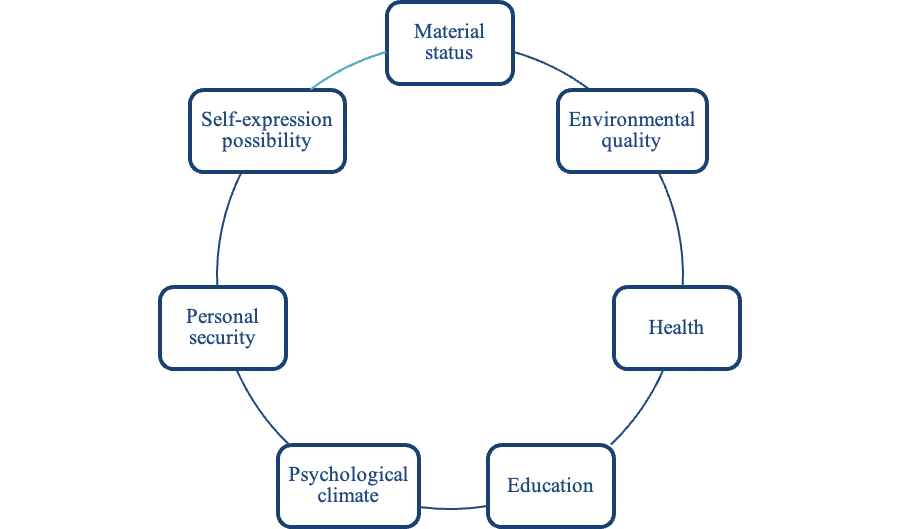

All these nine indicators can be structured into broader aspects. So in general, it can be said that the QOL contains seven main aspects which are also closely related to each other (Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1. The main aspects of QOL

(Source: developed by the authors using Akranavičiūtė & Ruževičius, 2007)

QOL can be interpreted according to individual priorities, the current stage of life, or one’s emotional condition, and the main aspects also can be just interpreted. Material status is more or less important for everyone, but its importance varies throughout life, because of changes in different areas such as economic situation, marital status, health and psychological condition, income, and purchasing power change every day. The quality of the environment is a slower changing factor – the issue of natural resources and sustainable development, especially water quality, air pollution, and soil cleanliness are more stable and there are not been so many changes in years. The education factor is about the ability to learn, education, skills, and knowledge appliance. The factor of health contains the health of the physical body and the psychological climate covers emotions, attitudes, values, self-esteem, job satisfaction, stress, relationships with people, family, society, and support. The security factor is about physical security, work environment, economic, political, and juridical environment. Recreation, hobby, creation, and entertainment are included in the self-expression needs.

It is also important to take into account the Human Development Index (HDI). In the last century, Suber (1996) suggests that QOL also depends on external factors. Good living conditions or circumstances will determine a high QOL, but if these conditions vary, the way individuals perceive QOL will also vary. QOL is influenced by a variety of factors and conditions such as amenities, employment rates, taxes, material well-being, moral attitudes, personal life, family, social support (or social services), stress and crises (state depression of a man), QOL related to health, health services, working conditions, food, school networks, relations with the environment, ecological and other factors.

The following combinations and sets of indicators are used to assess the QOL. It includes several different factors – first, it can be described as the basic literacy rate, infant mortality, and life expectancy at age one. The second important factor is more general and includes areas such as material living conditions, productive or main activity, health, education, leisure and social interactions, economic and physical safety, governance and basic rights, and environment. And the third factor is material welfare, political stability, and security, social life, climate, geographical location, and the freedom of politics and gender. Zeenea (2023) believes that when assessing the QOL, it is very important to consider and self-evaluate these aspects of data quality: uniqueness, completeness, timeliness, accuracy, validity, availability, consistency, traceability, and clarity. Four domains common to QOL in health have been defined as physical, mental, social, and functional health.

Quality of Life in the Cities and Countries

There are many indicators to measure or analyze the QOL. World globalization processes determine and influence the different levels of QOL of the population in different countries (Gineikiene et al., 2016; Ruževičius, 2007, 2012, 2014). By referring to these indicators, the international consulting firm Mercer Human Research establishes QOL measures and each year conduct a survey on QOL in cities around the world. It is intended to help governments and large companies choose the assignment of their personnel expatriate. 39 criteria were reviewed to achieve this ranking (Mercer, 2007; 2012; 2020):

- political stability, criminality, law enforcement;

- censorship, attacks on individual freedoms;

- exchange rate regulation, banking services;

- level and availability of international schools;

- leisure equipment;

- medical supplies and services, infectious diseases, disposal of waste, air pollution, etc.

For the evaluation of the integral QOL indicator and its ranking in various countries and cities of the world, scientific organizations use sets of evaluation indicators of different scopes. As a result, the ratings of the evaluation objects are somewhat different, but they reflect the most important trends in the QOL (Mercer, 2019; Numbeo, 2023; Ruževičius, 2014) – see below (Table 1.1 and 1.2, and Figure 1.2, 1.3). Since 2012, in addition to QOL, Mercer Human Research has also started evaluating the ecological QOL in the world’s cities (Mercer, 2012). One of the authors of this chapter also has proposed another new indicator, integrating the Mercer eco-city index and the QOL index, namely the “Total quality of life index”. The essence and content of this indicator are detailed in the article (Ruževičius, 2014). The evaluation encompasses 39 criteria of the QOL and in this list European cities overwhelmingly. For example, in the first place was Vienna (Austria) city, in second – Zurich (Switzerland), and third – Auckland (New Zealand), in fourth – Munich (Germany), fifth – Vancouver (Canada), sixth was Dusseldorf (Germany), seventh – Frankfurt (Germany), the eighth – Geneva (Switzerland), ninth – Copenhagen (Denmark), and the last of the top ten list – Bern (Switzerland) (Mercer, 2012). Baghdad (Iraq) ranked 221 – the worst city in the whole world from the perspective of the QOL, the worst city in the world is Baghdad (Iraq), which was ranked 221.

The ecological quality of cities around the world is also ranked and reflects some environmental indicators. In 2010 Calgary (Canada) was rated as the best ecological city in the world, in second position was Honolulu (USA), Ottawa (Canada), and Helsinki (Finland) took joint third place. From the perspective of the indicator of the total QOL, the top city in the world should be Auckland (New Zealand) (third position according to the QOL, and thirteenth based on eco-quality). From the viewpoint of this indicator, in first place Auckland (New Zealand) (3+13=16), second – Copenhagen (Denmark) (17) and Ottawa (Canada) (17), in third – Vancouver (Canada) (18) and Wellington (New Zealand) (18), fourth – Zurich (Switzerland) (21), fifth – Bern (Switzerland) (23), sixth – Stockholm (Sweden) (28), seventh – Helsinki (Finland) (35), and the eighth – Montreal (Canada) (36) in the top 10 list cities in the world.

In 2019, Mercer has released a separate personal safety ranking dominated by Western Europe, and where the safest city in the world was named Luxembourg. On a global scale, Vienna leads the ranking for the 10th year in a row, followed by Zurich (Mercer, 2020). Due to the ongoing changes in living conditions around the world due to the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic, the publication of Mercer’s Quality of Living City ranking has been suspended for 2020-2022.

Table 1.1. TOP 20 cities of the World ranked according to QOL index, 2023

|

Rank in the world |

City, Country |

QOL index |

|

1 |

217.7 |

|

|

2 |

207.1 |

|

|

3 |

202.5 |

|

|

4 |

201.3 |

|

|

5 |

199.2 |

|

|

6 |

193.1 |

|

|

7 |

191.0 |

|

|

8 |

191.0 |

|

|

9 |

189.6 |

|

|

10 |

189.2 |

|

|

11 |

188.7 |

|

|

12 |

183.5 |

|

|

13 |

182.4 |

|

|

14 |

182.0 |

|

|

15 |

181.4 |

|

|

16 |

180.0 |

|

|

17 |

180.0 |

|

|

18 |

180.0 |

|

|

19 |

179.5 |

|

|

20 |

179.2 |

(Source: Nombeo, 2023)

Table 1.2. TOP 20 countries of the World ranked according to QOL index, 2023

|

Rank in the world |

Country |

QOL index |

|

1 |

Netherlands |

196.7 |

|

2 |

Denmark |

194.7 |

|

3 |

Switzerland |

193.6 |

|

4 |

Luxembourg |

192.9 |

|

5 |

Finland |

190.5 |

|

6 |

Iceland |

187.5 |

|

7 |

Austria |

185.8 |

|

8 |

Oman |

184.7 |

|

9 |

Australia |

183.0 |

|

10 |

Norway |

182.7 |

|

11 |

Germany |

179.0 |

|

12 |

New Zealand |

176.7 |

|

13 |

Japan |

176.3 |

|

14 |

Sweden |

175.8 |

|

15 |

United Arab Emirates |

175.7 |

|

16 |

Spain |

173.8 |

|

17 |

United States |

172.7 |

|

18 |

Estonia |

171.9 |

|

19 |

Slovenia |

169.3 |

|

20 |

Qatar |

167.5 |

(Source: Nombeo, 2023)

Table 1.2 shows that according to the QOL level, only European cities are in the first top 20. Among the world’s 245 cities ranked according to the QOL, the worst are rated Tehran, Iran (241st), Beirut, Lebanon (242), Dhaka, Bangladesh (243), Lagos, Nigeria (24) and Manila, Philippines (245th) (Nombeo, 2023).

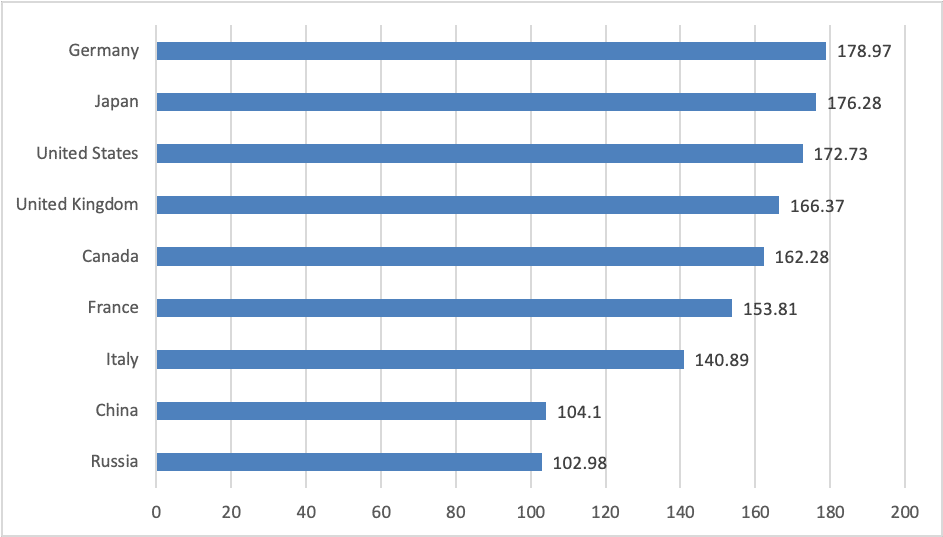

Figure 1.2. Benchmarking of the level of QOL in the countries of the world

(Source: compiled by the authors using Nombeo, 2023)

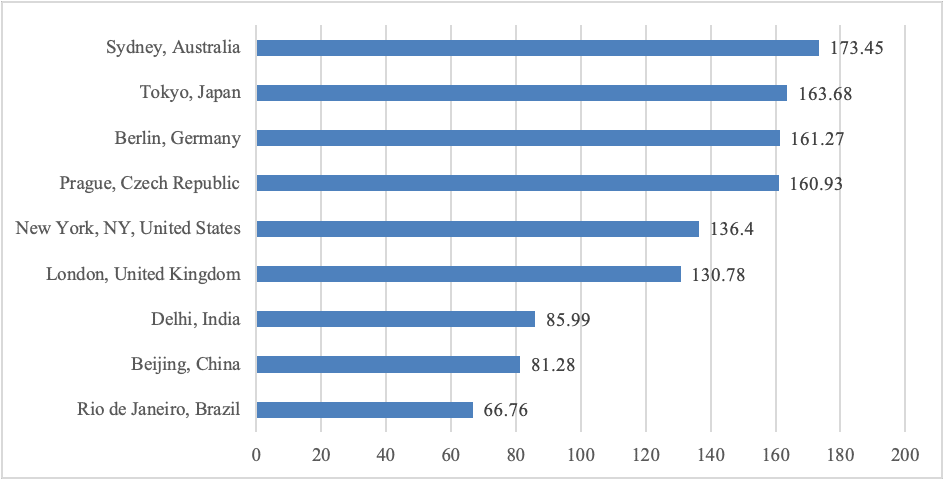

Figure 1.3. Benchmarking of the level of QOL in the cities of the world

(Source: compiled by the authors using Nombeo, 2023)

Figures 1.2 and 1.3 show a comparison of the level of QOL in the countries and cities of the world. These countries lead the world in terms of QOL – Netherlands (1st), Denmark, Switzerland, Luxembourg, and Finland. Meanwhile, it was recognized as one of the 5 best cities in the world The Hague, Eindhoven, Vienna, Luxembourg, and Rotterdam.

The Concept of Quality of Working Life and its Components’ Measurement

QWL is the most important element of QOL. This facet of QOL was not analyzed enough in the scientific literature. In the Cambridge Dictionary, the QWL has a definition that it is the level of happiness and satisfaction of an organization’s employees with their work. Furthermore, the definition of QWL can be found as it is a multidimensional construct focusing on worker wellbeing. The QWL (including working conditions) is a subject for many such studies that look at health and employee well-being, employment guarantee, career plan, skills development, the boundary between private life and professional life, and other considerations. The study of the factors that influence working conditions can lead to the establishment of social programs or the application of common policies at national or international.

The QWL can be defined as a concentrate that brings together the environment, the processes, and the strategies carried out in workplaces to boost employee job satisfaction (Akranavičiūtė & Ruževičius, 2007; Ruževičius, 2012; 2014; Von de Looi, 2003;). It also depends on working conditions and organizational efficiency. The QOL of individuals in their workplaces directly influences the very conception of life. In general, the QOL is also determined by satisfaction experienced by an employee or employee about the quality of their work environment. All components of QOL are interdependent and influence satisfaction among individuals regarding their QOL.

The concept of professional QOL covers the following elements: satisfaction at work, involvement in performance to work, motivation, efficiency, productivity, health, safety and well-being at work, stress, workload, exhaustion, etc. These factors can be identified as the physical and psychological consequences that affect workers at work. Other authors suggest including in this concept more labor factors: compensation fair, valid working conditions on the hygienic and psychological level, opportunities for deepening knowledge and opportunities to advance one’s qualifications, social integration, and relationships, the balance between professional and personal life, work plan and organizations (Akranavičiūtė, 2007; Ruzevičius, 2010). Some factors that define the QWL are the same as those that define the QOL except that they are related to the profession and working environment of employees. The characteristics of the QWL are as follows (Akranavičiūtė & Ruževičius, 2007; Shin, 1979; Sirgy et al., 2001, 2008; Ruževičius, 2010):

- Attitude towards work (material and non-material).

- Emotional state (appreciation, esteem, personal motivation, job satisfaction work, job security).

- Training and promotion (possibilities career, acquisition of new knowledge and skills).

- Social relations in the company (relations with colleagues and superiors, delegation, communication, management, work division).

- Personal development (career opportunities, involvement in the decision-making process, etc.).

- Physical state (stress, fatigue, exhaustion, workload).

- Safety and working environment, et al.

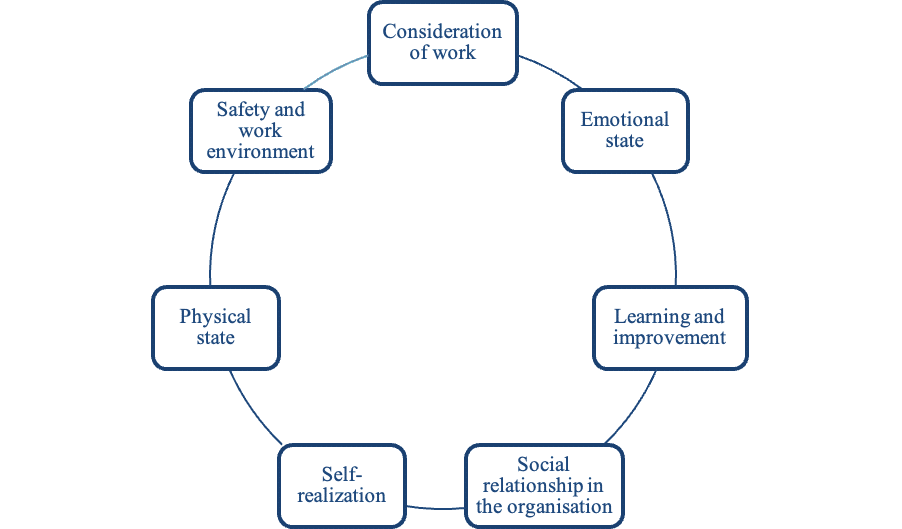

It is an interrelated concept affecting employees’ health and safety, productivity, and overall satisfaction with their job. QWL also encompasses a wide range of factors such as job satisfaction, job involvement in performance, motivation, stress management, safety issues at work, and well-being on the job, workload, burn-out (Ruževičius, 2014). The QWL is strongly related to higher work engagement and lower burnout. Some QWL factors related to the employee’s working environment and job are reflected in the model we provide (Figure 1.4).

Figure 1.4. The main aspects of the QWL

(Source: developed by the authors based on the information of Ruževičius, 2007)

According to Figure 1.4, the QWL contains material and non-material aspects. Emotional state includes honor, appreciation, self-motivation, job satisfaction, and how the employee feels safe for the job. Career opportunities becoming more important in acquiring new knowledge and skills, so they are in the category of learning and improvement but also is in the self-realization category. Social relationship in the organization is unavoidable so good relations with team and managers, internal communication, division of labor, and delegation is important as well. Physical state is one of the things which will not be evaluated before employment – it contains stress level, fatigue, burn-out, and workload (Ruževičius, 2007).

One can discover such dimensions of QWL: salary, environment, relationships, evaluations, atmosphere, control, time allocated, clarity of role, fairness, learning, the usefulness of work, happiness, etc. The QOL must be assessed according to subjective and objective criteria. Objective criteria can be measured, counted, and evaluated. While the subjective criteria relating to the QOL are buried in the consciousness of individuals, researchers can identify them by interviewing individuals. A complete search should include these two criteria. work and the environment of work directly influences the quality working conditions of employees. The high-quality working conditions arouse employee loyalty to the company and the decision to work there.

There is no unified and unique search methodology and model relating to the QOL at work evaluation. QWLs are measured according to both subjective and objective criteria. The study should answer the following questions: to what extent do particular factors affect people’s QOL and how satisfied are these individuals with these factors? The lack of satisfaction is an area where the QWL must not obliterate the QOL of individuals in general. On the other hand, an overvaluation bias of the factors that determine the QOL leads to a deterioration in the level of QOL, taken in a general sense. In the consciousness of individuals, the QOL domains are ordered hierarchically. The QOL, taken in a general sense, ranks first, as for the other domains, their classification depends on each individual’s subjectivity (Sirgy et al., 2001; Ruževičius, 2007). One more great satisfaction in an induced field is an increase in the level of satisfaction in the upper stratum. For example, high-quality working conditions increase the QOL, taken in its meaning wide. However, the lack of satisfaction in a QOL domain would not be likely to influence other areas. If a person finds no satisfaction in his or her work, he or she will compensate for this by giving more attention to her family and social relationships.

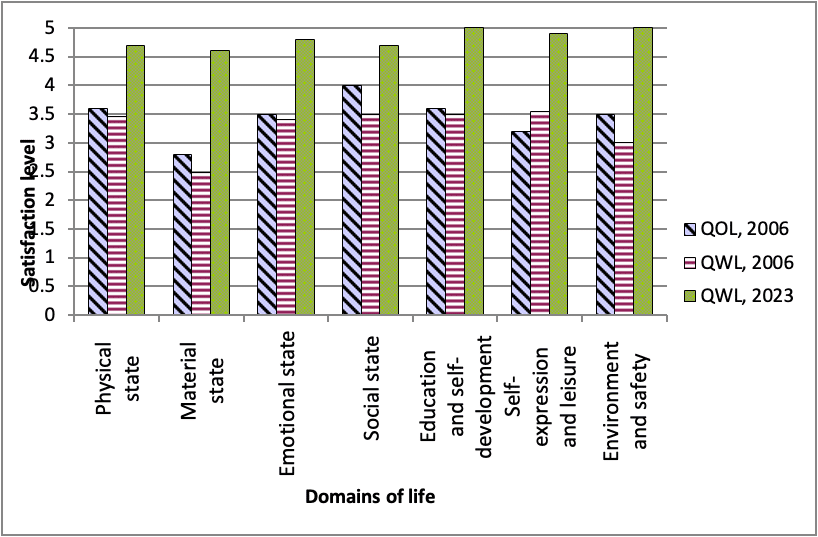

The authors of this chapter conducted a longitudinal (2005-2023) study of a medium-sized company from Lithuania, with interim measurement of QWL and correction actions in 2007, 2014, and 2023. The methodology of this research 2007 and 2014 the results of the study are published (Akranavičiūtė & Ruževičius, 2007; Ruževičius, 2014). The latest, 2023 research data is reflected in Figure 1.5.

Figure 1.5. Evaluation of QOL and QWL domains

(Source: 2023 – authors own study and calculation; 2006 – Akranavičiūtė & Ruževičius, 2007).

Figure 1.5 shows that the researched organization is constantly and consistently improving in the field of QWL, and the recommendations provided by the authors of the study are successfully implemented, and they provide positive results for improving the QOL of employees. The research findings showed that the analyzed organization can increase their employee satisfaction with QOL and loyalty by improving the working conditions and environment. High QWL evaluation can influence a higher QOL in general. The author of this study concludes that with the active actions of the organization’s top management and universal support for innovation, the QWL can be managed, measured, systematic improvement, and evaluated.

Although the QOL and QWL consist of quite different components, there is no doubt that they are closely related. In addition, QWL is closely interrelated with and inseparable from other areas of QOL in multiple ways, such as the individual’s physical and emotional state, self-realization, social life, education, development, and material well-being (Ruževičius, 2014). That positive correlation also was proven in the research which was done in Malaysia. In that study participated 179 employees who work at multinational companies in Bintulu, Sarawak. Data for the study were collected by distributing questionnaires to respondents who were randomly selected. Most respondents were females, about 29 years old. The research showed that there is a significant and positive relationship between the QWL programs and QOL and also between the work environment and QOL (Hassan et al., 2014).

The following indicators also can suggest that a company has a good QWL: decrease employee absence and increase turnover vs employee turnover, fewer accidents, improved working relationships, positive employee attitudes toward their work and the company, increased productivity and intrinsic motivation, employee personification, greater organizational effectiveness, and competitive advantage, and employees gain a high sense of control over their work.

Work-Family Conflict in the Context of Work-Life Balance

It is often difficult for a person to balance the roles of an employee and a family member, work, and family. The term “family conflict” is used to characterize the QWL conflict between work and family areas (Edsel, L. B. Jr, 2014; Pribušauskaitė & Ruževičius, 2015). Having analyzed the concept of the QOL and its correlation with the QWL, and also reviewed the elements that affect QWL, it is possible – from each of the theoretical and practical points of view – to analyze the relevant aspects of the balance of work and personal life; such research would be most natural in the context of work-family conflicts (Ruževičius, 2012; 2014; Ruževičius & Braškutė, 2015). Work and family are the two pivotal areas in human lives, however, very frequently humans stumble upon outstanding difficulties s whilst searching to combine them in such a way that neither of them suffers.

Based on the literature review (Byrne, 2005; Edsel, L. B. Jr, 2014; Pichler, 2009; Rode et al., 2007), the authors of this chapter distinguished three types of work-family conflict: time, behavior, and strains. Arising work-family conflicts determine the QOL in general – less time is allocated to family, leisure time, and physical condition, and the QWL also deteriorates – they are not properly fulfilled work duties.

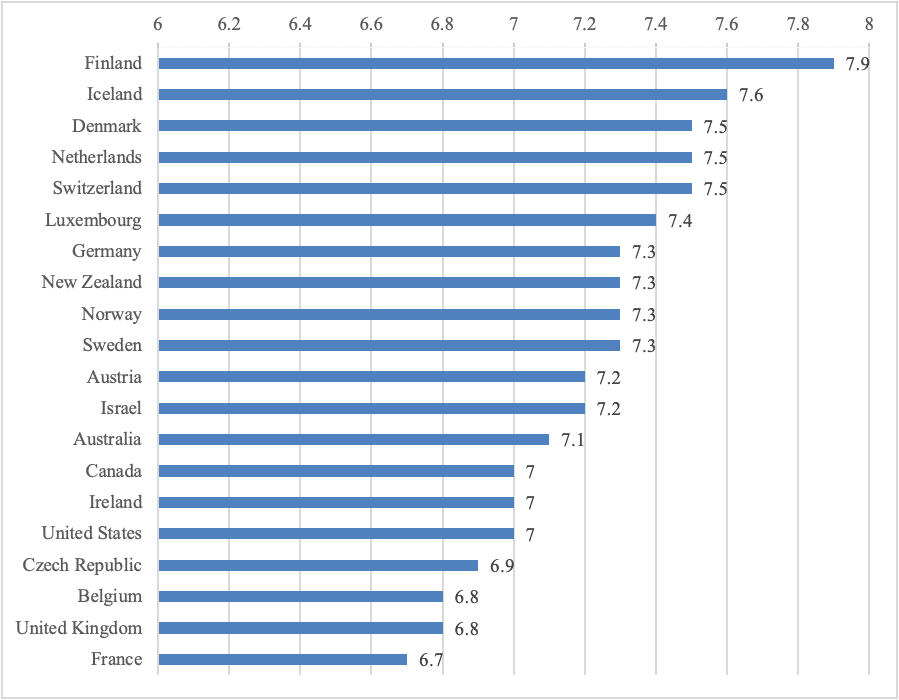

Equally, the higher QOL and QWL evaluation also depends on the country where respondents live. The leading countries in terms of the highest life satisfaction index are Finland (7,9), Iceland (7,6), Denmark (7,5), the Netherlands (7,5), and Switzerland (7,5) much higher than the OECD average of 6.7 on a 10-point scale (Figure 1.6).

Figure 1.6. Top 20 countries by the life satisfaction index, average score

(Source: compiled by the authors based on the information of OECD, 2023).

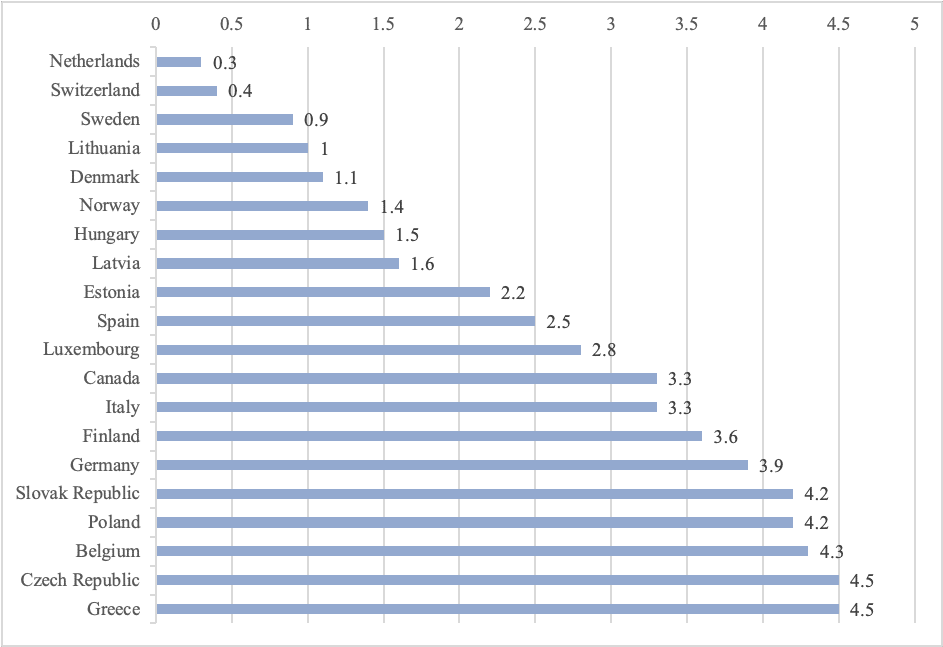

Since the evaluation of the QOL is closely related to the evaluation of the QWL, it can be said that the countries with the highest life satisfaction index are well evaluated because they have the lowest percentage of employees working overtime. Only 0,3 percent of employees are working overtime in the Netherlands, in Switzerland – 0,4 percent, in Sweden – 0,9 percent, in Lithuania – 1 percent, and in Denmark – 1,1 percent (Figure 1.7).

Figure 1.7. Top 20 countries by not working long hours, percentage

(Source: compiled by the authors based on the information of OECD, 2023).

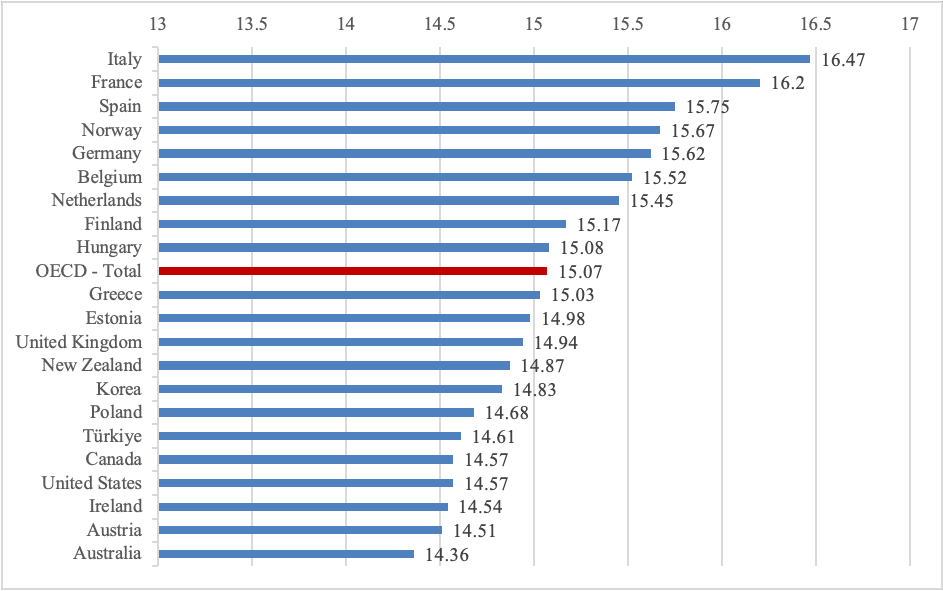

It is also important to mention that the life satisfaction index is influenced not only by not working overtime but also by the time spent on quality leisure time. The leading countries in the devoted time to leisure and personal care are Italy (16,47 hours) and France (16,2 hours), others devote little less – Spain (15,75 hours), Norway (15,67) and Germany (15,62) however, they are still above OECD average (Figure 1.8).

Figure 1.8. Top 20 countries by devoted time to leisure and personal care, hours

(Source: compiled by the authors based on the information of OECD, 2023).

Summarizing Figures 1.6, 1.7, and 1.8 the Netherlands scores well in many dimensions of well-being compared to other Better Life Index countries. The Netherlands outperforms the average in jobs, work-life balance, education, environmental quality, social networks, civic engagement, safety, and life satisfaction. In this country, almost 0 % of employees work very long hours in paid work, below the OECD average of 10 %. This is a very good result that all countries should strive for. To be more detailed 1 % of men work very long hours in paid work compared with 0% of women, so in the Netherlands full-time workers devote 64% of their day on average, or 15.4 hours, to personal care (eating, sleeping, etc.) and leisure (socializing with friends and family, hobbies, games, computer and television use, etc.) – it is more than the OECD average of 15 hours as well. These aspects can determine that the Dutch people have a high rate of life satisfaction.

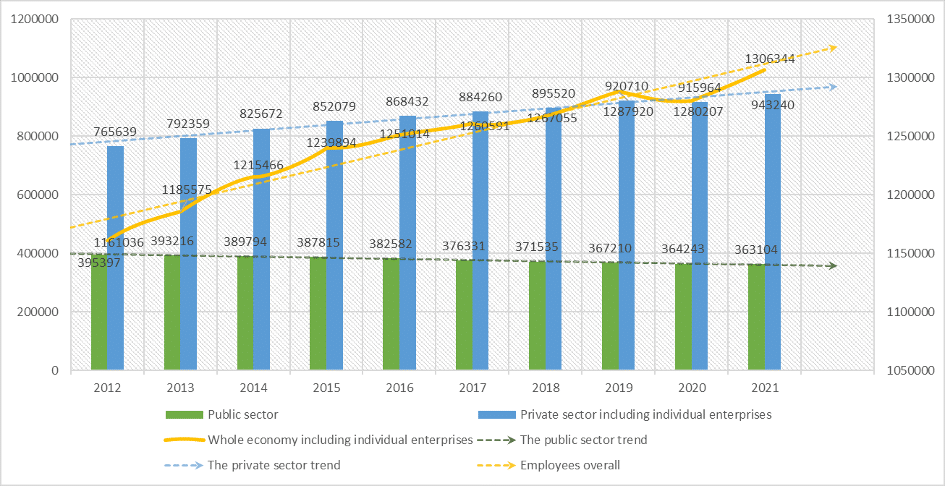

Quality of Life and Quality of Work and Personal Life Balance in the Public and Private Sectors in Lithuania

The differences in the assessment of the QOL and the QWL can also be determined by where the employee works – the private or public sector. Therefore, the authors conducted a comparative study in Lithuania to clarify these differences. Public sector – includes budgetary institutions and organizations (education, health care, social work, culture, public management, etc.), as well as public institutions, and companies, 50% of which or more of the entity’s authorized capital consists of state or municipal property. First of all, it can be stated that the number of people working in the private sector in Lithuania tends to increase, while those who would choose the public sector are decreasing. It is also important to mention that the average number of employees in the national economy, including individual companies, was 1,306,344 in 2021, in the private sector – 943,240 (72.2 percent of the national economy employees), in the public sector – 363,104 (27.8 percent of the national economy employees). The number of employees increased by 2 percent compared to 2020 (26,137). In the private sector, the number of employees grew by 3 percent. (27,276), while in the public sector, it decreased by 0.3 percent during the year (1,139) (Figure 1.9).

Figure 1.9. The average number of employees by sector in Lithuania

(Source: compiled by the authors based on the information of the Lithuanian Department of Statistics, 2023).

The average number of employees in 2021, compared to 2020, varied unevenly in companies and institutions of different types of economic activity. For example, the average number of employees increased the most in transport and storage companies, while wholesale and retail trade decreased the most; in motor vehicle and motorcycle repair and educational companies and institutions (Lithuanian Department of Statistics, 2023). Furthermore, from Figure 1.9, it can be seen that the trend will be the same in the future – employees in the public sector will increase, and overall employees also will increase (this may be determined by the increasing retirement age in Lithuania), whilst the number of employees in the public sector will be decreased.

The decreasing number of employees in the public sector led to the relevance of the topic and scope of the research – after all, why employees not only no longer choose to work in the public sector, but prefer to move to work in the private sector. At first glance, the public sector can appear very attractive to an employee looking for a job, because there is a public opinion that employment in the public sector is safe and the probability of being fired is very low. There are full guarantees, no overtime, no additional work, light workload, you just need to work from 8 am to 5 pm every day. Knowing this well-established opinion, it was hypothesized that the QOL, the QWL, and the balance between them are better appreciated by those working in the public sector than in the private sector. In this study, participated 71 employees from the private sector and 236 from the public sector. The developed questionnaire consisted of 157 questions. All questions were separated into blocks – the first block captured participants’ demographic information (gender, which age group the respondent belongs to, in which income bracket their monthly remuneration falls, education, and in which sector they work – the public or private). The remaining 152 questions were intended for QOL and QWL assessment: the first cluster (71 questions) of respondents to ascertain the QOL, the second (55 questions – of the QWL, and a third (26 questions) – about respondents’ QOL and QWL balance. In all three blocks of questions inquired to reply to each assessment of a five-point Likert scale, where 1 implies “totally disagree” and 5 implies “totally agree”. The data analysis was conducted with IBM SPSS Statistics 23 (tests: Pearson, Spearman, and Kendall’s tau-b tests were used).

A total of 307 employees participated in the study, including 251 women and 56 men working in the public or private sector. Most of the respondents belonged 46-55 age group, while fewer respondents were 26-35 years old. Most of the respondents were employees of middle-income groups – they belong to the group of “301-600 EUR” earners (in Lithuania, the average wage in the national economy in the fourth quarter of 2015 after taxes was 584.80 EUR (Lithuania of Social Security and Labour: in 2016) and only a little less than a third of the respondents earn more than the average wage. Most of the respondents have a university master’s degree while less than half – have a higher bachelor’s degree, and the least – have a secondary and higher doctorate.

The study found that overall, respondents were more satisfied with QOL, at least satisfied with QWL, with an average rating of 2.93 for QOL and 2.59 for QWL on a five-point Likert scale. The differences were statistically significant as p=0.000 (<0.05) and T-test value 15.041. Comparing the respondents’ answers of the private and public sector, it was found that there is no statistically significant difference between the private and public sector employees when assessing the QOL (p=0.051) and the QWL (p=0.561), but there is a statistically significant difference in assessing the balance of these qualities (p=0.003). Private sector employees have a better assessment of the QOL and QWL balance (M=2.814) than public sector employees (M=2.558, t=-2.952, p=0.003), so hypothesis h1 was raised during the study and which states that employees working in the public sector, to assess a better QOL and QWL balance than private sector workers were rejected. This result could also be because the private sector is increasingly offering the opportunity to work remotely from wherever you want. The author’s analysis and Pearson’s test using the SPSS package revealed that there is a moderate positive relationship between QOL and QWL and between the private (Pearson R=0.345, p=0.003) and between the public (Pearson R=0.435, p=0.000) sectors employee evaluation. The results of public sector employees revealed that there is a weak positive relationship between their assessment of QOL and QWL balance (Pearson R=0.167, p=0.010), but when analyzing the answers given by private sector employees, no such relationship could be found at all (p= 0.268). The assessment of public sector employees revealed an average positive relationship between QOL and QWL balance (Pearson R=0.436, p=0.000), but no such relationship could be found for private sector employees (p=0.075). There is an inverse relationship between age category and QOL – the older age category the respondent belongs to in the public sector, the worse they tend to assess the QOL (Spearman R=-0.199, p=0.002), but, interestingly, this relationship was not detected at all among those working in the private sector (p=0.673). It can be assumed that this result is because the average age of respondents working in the public sector was higher than in the private sector. Therefore, such an inverse relationship was due to problems felt by older respondents as age-related health problems, a slower pace of life, lack of movement, and active leisure time.

The conducted research also revealed the main criteria that are the most important for both private and public sector employees in assessing the QOL and the QWL. The results of the research revealed that employees working in the public and private sectors have different values on the importance of QOL elements. The assessment of the QOL of employees who work in the public sector is mostly determined by stressful situations, or rather – their absence, social life, and healthy lifestyle are also of great importance. In the private sector, a lot of attention is paid to reducing stress and stressful situations, but, unlike in the public sector, stability, clear requirements, and openness to innovation and challenges become extremely important factors. Both private and public sector workers singled out the most necessary element deciding their QWL – enjoyable work, which is like the basis of the QWL. However, the next most important factor is already different – for employees working in the public sector, the constant workload is the most important, while in the private sector, the most important factor is a good relationship with the direct manager and team. The third most important factor which was the “Pleasant and supportive atmosphere” overlaps in both sectors (Figure 1.10).

|

Quality of Working Life |

Quality of Life |

|

Public sector employees |

1. Enjoyable work 2. Adequate workload 3. Pleasant and supportive atmosphere |

1. No stress 2. Social needs 3. Healthy lifestyle |

|

Private sector employees |

1. Enjoyable work 2. Good relationship with the manager 3. Pleasant and supportive atmosphere |

1. No stress 2. Clear schedule 3. Opportunities for improvement |

Figure 1.10. A model that reflects the most important criteria for QOL and QWL by working sectors in Lithuania

(Source: compiled by the authors based on the information of the Impulevičienė & Ruževičius, 2021).

Analyzing only the evaluations of men working in both the public and private sectors, a moderate direct relationship between QOL and QWL was found. The higher men rate the QOL, the more likely they are to rate the QWL. Also, the results of the study revealed that women working in the private sector rate the balance of QOL and QWL better than women working in the public sector. However, the QOL and the QWL are valued equally by both groups of women. Although there is a direct relationship between women’s assessment of the QOL and the balance of work and personal life, it is very weak (p=0.001, R=0.203). When assessing the influence assessment of the QOL and the QWL of women working in the public sector on the general construct, it was found that if a woman works in the public sector, her overall quality assessment will be lower than that of a woman working in the private sector. The general model of quality assessment, depending on the sector in which the woman works, and which explains 71.7% of the total points of the construct, can be expressed by the following formula:

;

This formula shows that even if the average of the QOL assessment and the average of the QWL assessment of two women working in different sectors will be the same, the overall quality assessment will be higher for the respondent who works in the private sector. Such a result is determined by belonging to one of the two sectors ( ), which has a coefficient with a minus sign. Therefore, if a female respondent works in the public sector, her quality assessment will be 0.105 lower than that of those working in the private sector.

Analyzing the results of the study with the Bivariate Correlation function, it was found that a statistically significant direct relationship was moderate (Pearson R=0.406, p=0.000) between the QOL and QWL evaluation.

In a global context, Lithuanians on average gave life satisfaction a 6.4 grade, lower than the OECD average of 6.7. However, it should be remembered that happiness well-being can be measured by the presence of positive experiences and feelings, life satisfaction, and the absence of negative experiences and feelings, and all these measures, although subjective, are a useful complement to objective data to compare the QOL across countries.

Conclusions and Insights

Nowadays, the basic human needs in Western society are largely satisfied. Therefore, higher-order needs, such as QOL often discussed and aspired to. The crucial question in such a situation is the concept itself, and it is ultimately unclear how best to evaluate it. It can be concluded that the QOL is a multidimensional concept, and QOL is a very sophisticated issue, with all the colors of the rainbow to be used in different human life areas and activities. The term QOL is also used to measure well-being. This term encompasses the QOL of a person, the QOL in a country or in a city, the QWL, and the QOL in general. The concept of QOL is also linked to the many characteristics that define professional life or QWL, namely: job and salary satisfaction, involvement in high-performance work, motivation, efficiency, productivity, safety, well-being at work, stress, the load of work, exhaustion, environment, relationships, evaluations, atmosphere, control, time allotted, clarity of role, fairness, learning, the usefulness of the work, personal development, etc.

To improve work-life balance and life in general an important aspect is the amount of time a person spends at work. Evidence suggests that long work hours may impair personal health, jeopardize safety and increase stress levels (Ruževičius & Valiukaitė, 2017). The more people work, the less time they have to spend on other activities, such as time with others, leisure activities, eating, or sleeping. So, the amount and quality of leisure time are important for people’s overall well-being and can bring additional physical and mental health benefits. No matter how we want or try to separate the QOL and the QWL into two separate poles, it is not possible to do so – these are two things that have a completely direct connection. The QOL and QWL and their balance are very relevant topics and it seems that their relevance will only increase in the future. Greater satisfaction with the QWL can be achieved if the goals of employees and organizations are aligned and it also will have a positive impact on QOL as well. It is also important to mention that not all factors determining the QOL or QWL are of equal importance. Some of the aspects are extremely important, while others are completely irrelevant, it may depend on a specific moment – different circumstances, psychological state, health, or situation may determine different importance for one or another constituent factor.

The authors of this study are also particularly pleased that our long-term research has revealed and proved that QOL and QWL can be measured, managed, and systematically improved; and that the recommendations of our study were positively accepted and evaluated by the leaders of the studied organization and by its top management. The author of this study concludes that for this success is especially important the active systematic actions of the organization’s top management and their universal and systemic support for innovation.

References

Akranavičiūtė, D. & Ruževičius, J. (2007), Quality of Life and its components’ measurement. Engineering Economics, Vol. 2, pp. 43-48.

Arts, E. J., Kerksta, J. & Van der Zee (2001). Quality of working life and workload in home help. Nordic College of Caring Sciences, pp. 12-22.

Brown, J., Bowling, A. & Flynn, T. (2004). Models of Quality of Life: A Taxonomy, Overview and Systematic Review of the Literature. European Forum on Population Ageing Research. [Online]. Available: https://groups.google.com/forum/#!topic/abohabibas/Hoi0W-STeYI

Cambridge Dictionary. [Online]. Available: https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/quality-of-working-life

Chung, M. Ch. (1997). A critique of the concept of quality of life. International Journal of Health Care Quality Assurance, Vol. 10, No. 2, pp. 80-84.

Considine, G. & Callus R. (2002). The Quality of Work Life of Australian Employees – the development of an index. University of Sydney.

Cummins, R. A. (2005). Moving from the quality of life concept to a theory. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, No. 49, pp. 699-706.

Dahlgaard-Park, S. M. (2009). Decoding the code of excellence – for achieving sustainable excellence. International Journal of Quality and Service Sciences, Vol. 1, No. 1, pp. 5-29.

Diener, E. & Suh, E. (1997). Measuring quality of life: economic, social, and subjective indicators. Social Indicators Research, Vol. 40, No. 1, pp. 189-216.

Dooris M. (1999). Healthy Cities and Local Agenda 21: The UK Experiences – Challenges for the New Millennium. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Online]. Available: http://heapro.oxfordjournals.org/content/14/4/365.full

Edsel, L. B. Jr. (2014), Who is happier? Housewife or working wife? Research quality life, No. 9, pp. 157-177.

Ferrer, A. (2004). Hapiness Quantified: A Satisfaction Calculate Approach. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Furmonavičius, T. (2001). Quality of life research in medicine. Biomedicina, Vol. 2, No. 1, pp. 128-132.

Gilgeous, V (1998). Manufacturing managers: their quality of working life. Integrated Manufacturing Systems, Vol. 9, pp. 173-181.

Gineikiene, J., Bodo, B. Schlegelmilch, B. B., Ruzeviciute, R. (2016). Our Apples Are Healthier Than Your Apples: Deciphering the Healthiness Bias for Domestic and Foreign Products. Journal of International Marketing, Vol. 24, No. 2, 2016, pp. 1-20, DOI: 10.1509/jim.15.0078.

Hassan, N., Ma‟amor, H., Razak, A, N. & Lapok, F. (2014). The Effect of Quality of Work Life (QWL) Programs on Quality of Life (QOL) among employees at multinational companies in Malaysia. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, Vol. 112, pp. 24 – 34.

Impulevičienė, J. & Ruževičius, J. (2021). A model of Lithuania for work-life quality balance: Private and public sectors. The Work-Life Balance Bulletin: A DOP Publication, Vol. 5, No. 1, pp. 22-26.

James, G. (1992), Quality of Working Life and Total Management. International Journal of Manpower, Vol. 13, No.1, pp. 41-58.

Juniper, E. F. (2002). Can quality of life be quantified? Clinical and Experimental Allergy Reviews, Vol. 2, pp. 57-60.

Kajzar, P. & Kozubkova, M. (2007). Quality of work life and job satisfaction. Life quality conditions in societies basing on information: proceedings, Vol. II, pp. 289-295.

Kazlauskaitė M. & Rėklaitienė R. (2005). The quality of middle-aged Kaunas residents. Medicina, Vol. 41, No. 2, pp. 155-161.

Lithuanian Department of Statistics, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://osp.stat.gov.lt/darbo-rinka-lietuvoje-2020/darbo-uzmokestis-darbo-sanaudos-ir-streikai/darbuotoju-skaicius

McCall, S. (2005). Quality of life. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Mercer (2007; 2020). Quality of living city ranking. [Online]. Available: http://heapro.oxfordjournals.org/content/14/4/365.full

Mercer (2012). Quality of living worldwide city ranking – Mercer survey 2012. [Online]. Available: http://www.mercer.com/press-releases/quality-of-living-report-2012

Merkys, G., Brazienė, R. & Kondrotaitė, G. (2008). Subjective quality of life as a social indicator: the public sector context. Public policy and administration, No. 23, pp. 23-38.

Numbeo (2023). Quality of life. [Online]. Available: https://www.numbeo.com/quality-of-life/

OECD, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://www.oecdbetterlifeindex.org/countries/lithuania/

Olfert, S. (2005). Quality of life leisure indicators. Community–University Institute for Social Research.

Pichler. F. (2009). Determinants of Work-life Balance: Shortcomings in the Contemporary Measurement of WLB in Large-scale Surveys. Social Indicators Research, Vol. 92, No. 3, pp. 449-469.

Pribušauskaitė, J. & Ruževičius, J. (2015) Working women and housewives: characteristics of their perception and evaluation of the quality of life. Lithuanian economic growth and stability strategic directions. Collection of Articles. pp. 192-205. Vilnius: Vilnius University Publishing House.

Rode, J. C., Rehg, M. T., Near, J. P. & Underhill J. R. (2007). The Effect of Work/Family Conflict on Intention to Quit: The Mediating Roles of Job and Life Satisfaction. Applied Research on Quality of Life, Vol. 2, No. 2, pp. 65-82.

Ruževičius, J. & Braškutė, R. (2015). Peculiarities of assessing the quality of life at work. The role of higher schools in society: challenges, trends and perspectives. Scientific works, 2015, Vol.1 (4), pp. 180-188.

Ruževičius, J. & Ivanova, S. (2019). Качество жизни на работе/Quality of working life. Аспекти публічного управління /Public Administration Aspects, Vol. 7, No. 1–2, pp. 81–94, doi:10.15421/15199.

Ruževičius, J. & Valiukaitė, J. (2017). Quality of life and quality of work life balance: Case study of public and private sectors of Lithuania. Quality – Access to Success, Vol. 18, No. 157, pp. 77-81.

Ruževičius, J. (2007). Working life quality and its measurement. Forum Ware International, Vol. 2, pp. 1-8.

Ruževičius, J. (2010). Globalizarea oi calitatea – Globalization and quality. Quality-Access to Success, Vol. 1-2, pp. 10-21.

Ruževičius, J. (2012). Management de la qualité. Notion globale et recherche en la matière / Quality management. Global concept and research on the subject. Vilnius: Maison d’éditions Akademinė leidyba. 432 p.

Ruževičius, J. (2014). Quality of Life and of Working Life: Conceptions and Research. 17th Toulon-Verona International Conference Excellence in Services Proceedings. Liverpool: Liverpool John Moores University, August 28-29, 2014, pp. 317-334.

Ruževičiūtė, R. & Ruževičius, J. (2011). Standardization-adaptation paradox in international advertising: the case of cultural and regulatory peculiarities in Lithuania. Business - science - government partnership: fostering country competitiveness conference proceedings: international scientific conference. Vilnius, 21-23 September, pp. 102-110.

Schoepke, J., Hoonakker, P. & Carayon, P. (2003). Quality of working life among women and men in the information technology workforce. Proceedings of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society 46th Annual Meeting, Baltimore, pp. 1379-1383.

Scoring the Quality of Life Profile. University of Toronto, 2003.

Shin, D. (1979). The concept of quality of life and the evaluation of developmental effort. Comparative politics, Vol. 2, pp. 299-304.

Sirgy, M. J., Efraty, D., Spiegel, Ph. & Lee, D. (2001). A new measure of work life (QWL) based on need satisfaction and spillover theories. Social Indicators Research, Vol. 55, pp. 21-32.

Suber, P. (1996). Against the Sanctity of Life. [Online]. Available: http://www.earlham.edu/~peters/writing/sanctity.htm

Susnienė, D. & Jurkauskas, A. (2009). The concepts of quality of life and happiness – correlation and differences. Engineering Economics, Vol. 3, pp. 58-66.

The Economist. Intelligence Unit’s Quality-of-life Index (2005). [Online]. Available: http://www.economist.com/media/pdf/QUALITY_OF_LIFE.pdf

Van de Looij & F., Benders, J (1995). Not just money: quality of working life as employment strategy. Health Manpower Management, Vol. 21, pp. 27-33.

Varghese, S. & Jayan, C (2013). Quality of Work Life: A Dynamic Multidimensional Construct at Work Place – Part II. Guru Journal of Behavioral and Social Sciences. Vol. 1, No. 2, pp. 91-104. ISSN: 2320-9038

Veenhoven R. (2000). The Four Qualities of Life: Ordering Concepts and Measures of the Good Life. Journal of Happiness Studies, Vol. 1, pp. 1-39.

Zeenea (2023). Zeenea data discovery platform - be data fluent. [Online]. Available: https://zeenea.com

WHOQOL: Measuring Quality of Life (2023). [Online]. Available: https://www.who.int/tools/whoqol

Comments