Chapter And Authors Information

Content

Abstract

The United States continues to be a study abroad destination for international students around the world. Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, the Institute of International Education’s Opendoors (2020) report shows that 1,075,496 international students came to the United States for education purposes during the 2019-2020 school year. Education abroad enrollment data from 2019 to 2022 shows international education is not only a large volume student operation, but a profitable business for U.S. colleges. With such a large-scale operation system of immigration, regulations, and money involved, there is a lack of training in relation to the ethics surrounding international education professionals. Utilizing an Integrity Pyramid guides international education workers to use their voice, listening skills, and core standards to stand on achieving a consistent and ethical decision-making process. Without the pressure of being untrained, these administrators can continue the satisfaction and work-life balance of working with an international student population in their role.

Keywords

International Education, Work-Life Balance, Ethics, Global Leadership, Study Abroad

Introduction

The United States continues to be a study abroad destination for international students around the world. Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, the Institute of International Education’s Opendoors (2020) report shows that 1,075,496 international students came to the United States for education purposes during the 2019-2020 school year. This data added to the U.S. enrollment of domestic students enrolled is 19,720,000, making international students represent 5.5 percent of all enrollment in the country (IIE Opendoors, 2020). With U.S. colleges returning to classrooms, in 2021-2022 international students enrolled in U.S. colleges were 948,519 (IIE Opendoors, 2022). Of the countries of origin, IIE Opendoors shows that in the 2019-2020 school year, 53 percent of all international students came from India and China. In 2021-2022, India and China made up 51.6 percent of all international students enrolled at U.S. colleges.

Depending on what the tuition rate is for a U.S. college, whether it be in state or out of state, the data from 2019 to 2022 shows international education is not only a large volume operation, but a profitable business for U.S. colleges. With such a large-scale operation system of immigration, regulations, and money involved, there is a lack of training in relation to the ethics surrounding international education professionals where attention is lacking to those in charge of this sector in higher education (Rosser et al., 2007). Establishing a strategy for ethics training for international education professionals will benefit the administration and students of tomorrow.

SEVIS Historical Roots

International education in the United States has gone through an increased change from the early 1990s to 2001. At first, an international student system was implemented after the Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act of 1996 for collection of basic information on international students (Rosser et al., 2007). After the bombing at the World Trade Center of 1993, Finley (2002, Sep 25) notes how congress transitioned to create the Student Exchange and Visitor Information System (SEVIS) in 1996. The goal of the system was to act as a national database to track international student and scholar mobility within the U.S. (Rosser et al., 2007). At first there was an eight-year loose deadline to get the software up and running, however, after the attacks of September 11th, 2001, the role of SEVIS jumped to involvement with the Department of Homeland Security after U.S. Congress funneled 37 million dollars to support the system meeting the deadline of 2002 (Finley, 2002; Rosser et al., 2007).

The Student Exchange and Visitor Program (SEVP) was created to bridge organizations in government who needed nonimmigration information in the U.S. for educational purposes (O’Connell, 2019). In modern times, data from SEVP (2018), who oversees SEVIS, showed 8,744 U.S. based schools were eligible to receive students from around the world by producing their visa request and allowing the student to finalize the request through a U.S. embassy near their home country. If each campus houses a Designated School Official or Responsible Officer under a Principal Designated School Official, both with secure access to SEVIS, then there are at least more than 16,000 employees with the power of a mouse click to grant access to an international student in the U.S. This level of responsibility to the School Officials is equated by those in admissions, where a Designated School Official resides in recruiting students who match the college’s requirements for acceptance through detailed documentation of finances and a degree timeline to follow while in the U.S. (Bowen & Foley, 2002).

Those who use SEVIS feel supported, however, have negative work effects of enforcement, government involvement, and an outlook on U.S. policy with educational governance (Boyd, 2008). If becoming a member of international education administration hinges on personal satisfaction of working with international students (Rosser et al., 2007), how can a college better prepare those administrators year in and year out in case there is a decline in that satisfaction? The same satisfaction may decline the ethical integrity of the person in the role and put the whole college at risk of having an immigration problem with the Department of Homeland Security. To understand how to ethically train those involved, there needs to be an understanding of where ethics can corrode within the international education system involving SEVIS immigration operations and why the ethical breakdown happens.

Integrity of International Education

F-1/J-1 Visa Procedure

The application cycle of an international student is similar to the U.S. student path in which applications are full of confidential documents to turn in. Colleges provide an investment return on human capital for those who seek an improved situation in their lives by going to college in the U.S. (Wendt, 2016). It is here that the F-1 visa is the most profitable for the college and the student as they are in the U.S. to obtain a degree at whichever level they have applied for (Boyd, 2008). The path can easily go from an associate’s to bachelor’s to master’s to doctoral as long as the student has the funds to pay for tuition. J-1 students are classified as an exchange and normally sponsored by the home college or government (Boyd, 2008). These students are typically in exchange for an outgoing study abroad student on a short-term basis. Since F-1 student visas are the largest handed out, federal policy imposed the first change on this category when implementing SEVIS (Boyd, 2008).

Where there are large amounts of international student applications, this is where the government has the most trouble regulating the population due to volume. This has caused situations of ethical downfall at colleges who looked to take advantage of students wishing to study in the U.S. An article from Miriam (2015) highlights an Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) raid on three SEVIS access employees who were in charge of four different schools in the Southern California region. The charge was a scheme to commit visa fraud, launder money, and multiple immigration offenses. Miriam (2015) stated the charged individuals promised education to those who paid fees of up to $1,800 to receive their Form I-20, the certificate of eligibility, to enter the U.S. and study. When the students arrived, there were no classes nor any assistance to figure out how to enroll in the college. The individuals in this scenario allowed the students to become out of status, which means they weren’t fulfilling their student requirements.

According to the Department of Homeland Security’s ICE (2019), being full time in course load at the college by working towards degree progression with no unauthorized work maintains the status of full time. On top of a full course load, The Department of Homeland Security (2012) mandates that international students must maintain full time status with at least two-thirds of the instruction to be face-to-face each semester. Incidents of F-1 visa fraud continued to surface so much that the Department of Homeland Security decided to create a fake university in order to catch all those involved (Mervosh, 2019).

U.S. Immigrations created “University of Farmington” in order to find F-1 fraud (Mervosh, 2019). The fake university was listed in SEVIS as a legit college in the U.S. and paid over $250,000 to recruiters to offer fake transcripts that drew in students. Recruiters in this case break the law as they are the ones who bring in students based on certain requirements, but with getting paid they bypassed the requirements of full-time status and face to face course loads. It’s obvious that the power of immigration to one person can and is exploited since the inception of the SEVIS program. There needs to be training surrounding those who access, recruit, and utilize SEVIS on a daily basis under SEVP approved schools in the U.S.

SEVIS Training

In order to gain access to SEVIS, a U.S. citizen working in international education submits documentation to the Department of Homeland Security for a background check. After that, the college can train as they please as long as the employee follows the procedures legally. Employees are in the hands of their training supervisor to do the rest. The SEVP administration does not offer or handle any training beyond what each college trains for ethical decision making.

NAFSA is the face of international education, being the biggest association for leaders around the world. They have principles and ethics on their NAFSA website (2019) for public use, however, the individual training opportunities are not linked to this page and are difficult to find. In fact, if an international education professional has funds, they can purchase a NAFSA lecture that has ethics involved, however, there is no formalized training for the system (NAFSA, 2015). A closer look at NAFSA F-1 for beginners training (n.d.) shows a curriculum that involves the governing agencies, F-1 visa status maintenance, and advising these students. There is no mention of ethics for decision making, only informed decision making on the laws. This is where ethical erosion can happen in between a decision and a law.

Not only does NAFSA miss an opportunity for beginners in the field, the association charges close to $500 for visa training without ethical guidance beyond the law. There is also the issue for those working in higher education to find funds for sourcing ethical training, where Stevens and Kirst (2015) state universities are constrained to develop funds in an era where state funding continues to decline. If the priority does not exist at the college, there will be no funding for ethics and continue to have a vulnerable gap surrounding SEVIS. The time is now for U.S. colleges to incorporate a mandatory ethics training for international education, an overdue topic in the field for decades (Rosser et al., 2007).

Ethical Approach to International Education

As soon as someone is verified in the system of SEVIS, there is no reverification process of documents or standards of the person acting as a Designated School Official, Responsible Officer or Principal Designated School Official who oversees a college’s Form I-17 that governs all information. There is a website through ICE (n.d.) that has reverification online, however, this just confirms all those who have access still work at the college, as fast as 20 seconds to complete. This is followed up by a once-a-year visit from a single SEVP representative for each state within the U.S (ICE, n.d.). ICE (n.d.) claims they now have 56 total reps for all 8,000 colleges in the U.S., providing a polarizing number of imbalances between auditing capabilities and onsite help from SEVP.

The launching of SEVIS placed international advisors, mid-level university employees, as caretakers for international students that further launched into the Department of Homeland Security’s data collection facilitators (Rosser et al., 2007). During this time, decision making had never reached such a critical level for these mid-level employees where decisions could change the fate of a student through U.S. entry bans to having the ability to work in the U.S. for a certain amount of time (Boyd, 2008). SEVIS had negative effects on mid-level administrations morale and caused a likelihood of quitting due to the pressure of the position of decisions adding up (Kim, 2007). Having an ethical training standard will help the pressure surrounding decisions felt by these administrators and give them the best confidence they can have to make the right decision every time. The logic is if the decision is ethically aligned, the pressure should be removed as there would be no grey areas.

International education leaders need to comprehend a culture in an organization before they can eliminate any ethical conflicts of standards by having a proactive process for removing bad ethical behavior is the foundation to this comprehension (Thoms, 2008). A college culture that values ethics and training will add to the elimination of ethical conflict. A lack of funds often prevents international education offices from having the best training resources, which leaves the best intentions as the guide for ethics in each office (Kim, 2007). If ethical training can survive as a core training method, then funds will be out of the concern because this training can pay for itself year after year with new and returning employees to the SEVIS role.

Ethics can be considered different depending on the culture context (Tsiu & Windsor, 2001). As a basis definition for this ethical training section, ethics are what a person, alone or in a community, should do by choice regarding what is considered right (Molawa, 2011). The use of community in this definition is appropriate because Kacmar et al. (2010) emphasized the integration of social role theory where over time communal or agentic patterns of behavior emerge and are thus repeated. This aligns with Thoms (2008) suggesting the organizational culture must be free of ethical lapses before any foundation of training can begin. Audi (2012) expands that need not only to the internal organization, but for the public view in a sense of judgement of an organizational standard by its ethics. Trevino et al. (2003) saw good decisions arrive from integrity, based on honesty and trust within a person. By focusing on an ethical training program that all international education administrators can use, characteristics of integrity are the foundation.

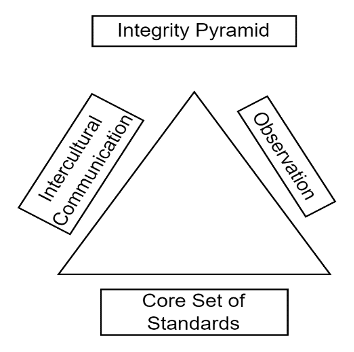

Integrity Pyramid

The integrity pyramid (Figure 4.1) can be the new training basis that this author envisions for ethics training for higher education colleges. The goal is to make the best decision arrive at the top by passing either side of the pyramid. Global leader duties involve continual development of integrity, within the individual and their connection to the organization (Morrison, 2001).

The first side of the integrity pyramid is strong observation. When duties go into different cultures, misunderstanding through communication increases and requires interpretation of behavior and practices to demonstrate integrity (Morrison, 2001). This requires active listening that is an ability to understand what is happening inside and outside of an organization (Weiming, 2014). There also needs to be curiosity, a competency of true interest in people and what they are doing through reflection that benefits long-term development (Caputo & Crandall, 2012; Morrison, 2001). The result of integrity observational skills is a flexible observational lens, one that is built for contextual leadership (Aritz & Walker, 2014).

The second side of the base of the integrity pyramid focuses less on observation and more on a vocal approach. In order to be successful, global leaders in international education accept that ethical erosion happens and can arrive at any moment. Such an environment requires the ability to ask difficult questions on what is right, including what behavior is right (Morrison, 2001). Intercultural communication takes part of this voiced concern for international education leaders since the skill can problem solve in a situation where different cultures collide (Kalscheuer, 2014). This requires having minimal intercultural apprehension, a block that prevents people from acting their true self when interacting with other cultures (Neulip, 2017). It is possible to host an ethics forum at the college, one that shows the global leader is constantly asking questions on ethics as well as providing open training to all those who can discuss policies (Morrison, 2001). Having an open discussion about ethics can begin cultural change if there are none in place for international education as well as other parts of the college.

The last section, at the base of the integrity pyramid, is a core set of standards. These standards are labeled as irrevocable, accepting the reality that the global leader in international education has so much influence, therefore they need the standards at the core that anyone can see exists (Morrison, 2001). A Principle Designated School Official, for example, needs to be implementing this core set of standards each year in the training because this role is the final say to all decisions for SEVIS. Whether this be a new program, updated program hours for face-to-face hours, or meeting with a SEVP representative, this role needs to be the global leader that emulates the integrity pyramid core standards.

There are three check points that determine if the standard is properly aligned with what core standards (Morrison, 2001). The first check point is relation to strategy, where the standard in question has an influence on the college’s reputation, it has to be considered part of the core (Morrison, 2001). Ethical leadership meets high standards of equality and transparency (Kacmar et al., 2010). The second check point is the quality of the standard, where low standards cannot be embraced by the leader (Morrison, 2001). This involves comparing to other competing colleges in order to make sure the standards are at the top level. Practical ethics define a good moral standard, therefore focusing on top level standards will make for practical ethical training at the college (Audi, 2012).

The final check point is the importance of people and the impact of the standard within the core. Integrity that is shown to people is also evaluated by people, meaning the decisions international education professionals make impact many people and almost always involve ethics (Morrison, 2001). There is a positive relationship with the values of leadership on a personal level and their overall effectiveness in their role (Bruno & Lay, 2008). A college is a driver in ethical behavior (Weaver et al., 2014), showing personal and professional effeteness comes from understanding the impact on people matters in not only their role, but the role of those around them (Bruno & Lay, 2008). The importance of integrity with this idea is that it’s not just the individual, but all involved (Morrison, 2001).

Figure 4.1. Integrity Pyramid

Note. The three sides of the Integrity Pyramid, observation, intercultural communication, and core set of standards.

Managerial Implications

Moving past a global pandemic of 2020 and back to a “new normal,” international education administrators yet again have to adapt to working environments that just went through an ever-changing last few years. Managers who work in and oversee international educators need to be aware of the mental state of their employees as well as themselves. If the U.S. attacks of September 11th had changed how the government received international students (Kim, 2007; Rosser et al, 2007), which added extra stress to roles not yet adapted, then managers need to adapt their approach and overall perception to work life balance. The first step for managers is to assess work life balance within themselves and teams.

Work life balance can be viewed as personal activities and paid work within someone’s day to day which ultimately affects the employee’s outlook on commitment to the organization as well as overall satisfaction (Noor, 2011). An individual’s quality of work life can benefit or hinder not only themselves, but what they do at the company or college. In the case of higher education, a lot of focus on work life balance is within the college faculty, whether in North and South America, to the Middle East, to Asia; specifically, with the impact of the work from stress and the working environment (Agha et al., 2017; Diego-Medrano & Salazar, 2021; Franco et al., 2021; Khairunneezam et al, 2017; Rosser et al., 2007). If work life balance leads to positive organizational outcomes (Agha et al., 2017; Noor, 2011), then managers within international education need to work with their staff to consider boundaries and policies to achieve a work life balance.

For international educators working with students from around the world, the integrity pyramid (Figure 4.1) serves a purpose to allow international education leaders, specifically those with access to immigration software and decision making, to be the best ethical leader. Social learning theory shows the emulation of follows of leaders (Brown & Trevino, 2006). When followers have to make their own decision, they can take comfort in knowing their leader would make the right choice and have used the integrity pyramid to train followers on how the right choice would be made. This ethics training formula should be used in the network of international education at colleges within the U.S, as well as with student service administrators, admissions counselors and recruiters, faculty advisors, and student affairs. Managers who oversees lower to mid-level administration rely on positive employee morale and retention and thus should familiarize themselves with the consistency of the integrity pyramid for consistent decision making from their teams in stressful situations. If lower to mid-level administration have a near twenty-five percent chance to leave the position in three to four years (Kim, 2007; Rosser et al., 2007), then managers need to understand that the addition of SEVIS after September 11th, 2001, burdened international educators in charge of admissions which in turn affected administrators concerning their work life balance, motivation, and tenure. Work life balance is important when managing new and current employees in the field of international education.

Conclusion

For those workers who feel too much pressure with decision making in international education (Kim, 2007; Rosser et al., 2007), utilizing the integrity pyramid allows managers and workers to use their voice, listening skills, and core standards to stand on achieving a consistent decision-making process. Without the pressure of what if and possible detrimental consequences, these administrators and their leadership can continue the satisfaction of working amongst an international student population in their role (Rosser et al., 2007). Even with complying with the Department of Homeland Security, each impactful role can let go any unethical worry knowing they have a foundation to rely on that complies with not only their college but the overseeing governance in the fields for U.S. colleges.

Bringing consistency in the department does not just satisfy a checkbox of ethical leadership, that like ethics in international education have yet to be fully explored nearly 18 years later (Brown & Treviño (2006), but the work life balance of the team. Having a compliance friendly decision-making process with the Department of Homeland Security will ensure managers and workers in international education. Having a solid foundation of the triangle along with the continual push from managers to focus on the work life balance not only of faculty within the international education programs, but the staff, will move the industry in a balanced direction. Changing the global perspective on quality of working life is important in this field that has a history of burning administrators out of their jobs given the circumstances of a rapidly changing environment. (Kim, 2007; Rosser et al., 2007). If higher education is slowly becoming more cognizant of the work life balance of the industry’s faculty around their world (Agha et al., 2017; Diego-Medrano & Salazar, 2021; Franco et al., 2021; Khairunneezam et al, 2017; Rosser et al., 2007), than international education must equally begin to acknowledge the emerging need of balancing work and life to maintain job satisfaction and tenure that benefits international students and colleges.

Acknowledgment

I’d like to acknowledge the international education workers in their respective countries that strive to create a welcoming environment to send and receive students while maintaining their work life balance boundaries.

References

Agha, K., Azmi F. T. & Irfan, A. (2017). Work-life balance and job satisfaction: An empirical study focusing on higher education teachers in Oman. International Journal of Social Science and Humanity, 7(3), 164-171. http://doi.org/10.18178/ijssh.2017.7.3.813

Aritz, J., & Walker, R. C. (2014). Leadership styles in multicultural groups: Americans and East Asians working together. International Journal of Business Communication, 51(1), 72-92. https://doi.org/10.1177/2329488413516211

Audi, R. (2012). Virtue ethics as a resource in business. Business Ethics Quarterly, 22(2), 273-291. http://doi.org/10.5840/beq201222220

Bowen, J. A., & Foley, C. J. (2002). The impact of SEVIS on the U.S. admissions office. International Educator, 11(4), 31–33.

Brown, M. E., & Treviño, L. K. (2006). Ethical leadership: A review and future directions. The Leadership Quarterly, 17(6), 595-616. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2006.10.004

Bruno, L. F. C., & Lay, E. G. E. (2008). Personal values and leadership effectiveness. Journal of Business Research, 61(6), 678-683. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2007.06.044

Boyd, L. E. (2008). A study of how international student services and policies have changed as a result of 9/11 (Order No. 3334528) [Doctoral dissertation, Boston University]. ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global.

Caputo, J. S., & Crandall, H. M. (2012). The intercultural communication cultural immersion experience: Preparing leaders for a global future. Journal of Leadership Studies, 6(1), 58–63. https://doi.org/10.1002/jls.21229

Department of Homeland Security. (2012). Know the Rules: Online and Distance Learning Classes. https://studyinthestates.dhs.gov/2012/07/know-the-rules-online-and-distance-learning-classes

Diego-Medrano, E., & Salazar, L. R. (2021). Examining the work-life balance of faculty in Higher education. International Journal of Social Policy and Education, 3(3), 27-36. www.icpknet.org

Finley, B. (2002, Sep 25). INS says system to track foreign students to be operational by January. Knight Ridder Tribune Business News

Franco, L. S., Picinin, C. T., Pilatti, L. A., & Franco, A. C. (2021). Work-life balance in Higher Education: a systematic review of the impact on the well-being of teachers. Ensaio: Avaliação e Políticas Públicas em Educação, 29, 691-717. https://www.scielo.br/j/ensaio/a/F3PPhBG6

ZVXsSvsVCTPV6Cw/

ICE. (n.d.) School. https://www.ice.gov/sevis/schools

IIE Opendoors. (2019). All destinations 2018-2019. https://opendoorsdata.org/data/us-study-abroad/all-destinations

IIE Opendoors. (2022). 2022 Fast Facts. https://opendoorsdata.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/Open-Doors-2022_Fast-Facts.pdf

Kacmar, K. M., Bachrach, D. G., Harris, K. J., & Zivnuska, S. (2011). Fostering good citizenship through ethical leadership: Exploring the moderating role of gender and organizational politics. Journal of Applied Psychology, 96(3), 633-642. http://doi.org/10.1037/a0021872

Kalscheuer, B. (2014). Encounters in the third space. Links between intercultural communication theories and postcolonial approaches. In Asante, M., K., Miike, Y., & Yin, J. (Eds.). (2014). The Global intercultural communication reader (2nd ed.). Taylor & Francis.

Khairunneezam, M.N., Siti Suriani, O., & Nurul Nadirah, A.H. (2017). Work Life Balance Satisfaction among Academics in Public Higher Educational Sector. International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences, 7, 5-19. http://dx.doi.org/10.6007/IJARBSS/v7-i13/3181

Kim, J. (2007). Effective organizational characteristics for international student enrollment service (Order No. 3301888) [Doctoral dissertation, Auburn University]. ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global.

Mervosh, S. (2019, Jan 31). ICE Ran a fake university in Michigan to catch immigration fraud. New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/01/31/us/farmington-university-arrests-ice.html

Miriam, J. (2015, Mar 11). Federal agents raid suspected fake schools--update. Dow Jones Institutional News. https://professional.dowjones.com/newswires/

Morrison, A. (2001). Integrity and global leadership. Journal of Business Ethics (31)1, 65-76. http://doi.org/10.1023/A:1010789324414

Mowlana, H. (2011). Communication and cultural settings. In Anderson, M. S., & Steneck, N. H. (Eds.). (2011). International research collaborations: Much to be gained, many ways to get in trouble. Routledge

NAFSA. (2019). Ethics Code. https://www.nafsa.org/about-us/about-nafsa/nafsas-statement-ethical-principles

NAFSA (n.d.). F-1 training for beginners. https://www.nafsa.org/professional-resources/learning-and-training/f-1-student-advising-beginners

NAFSA. (2015). Service through learning, ethics, partnerships, and best practices. https://www.nafsa.org/professional-resources/learning-and-training/service-through-learning-ethics-partnerships-and-best-practices

Neuliep, J. W. (2017). Intercultural communication apprehension. The International Encyclopedia of Intercultural Communication, 1-5. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118783665.ieicc0045

Noor, K. M. (2011). Work-life balance and intention to leave among academics in Malaysian public higher education institutions. International Journal of Business and Social Science, 2(11), 240-248. https://www.academia.edu/download/30909401/34.pdf.

O'Connell, T. (2019). Stakeholders’ perceptions of the 2010 English language training program accreditation act (Order No. 27540396) [Doctoral dissertation, Boston University]. ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global.

Rosser, V. J., Hermsen, J. M., Mamiseishvili, K., & Wood, M. S. (2007). A national study examining the impact of SEVIS on international student and scholar advisors. Higher Education, 54(4), 525-542. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10734-006-9015-7

Stevens, M. & Kirst, M. (2015). Remaking college: The changing ecology of higher education. Stanford University Press.

Student and Exchange Visitor Program. (2018). SEVIS by the numbers: Biannual report on international student trends. https://studyinthestates.dhs.gov/2018/05/check-out-the-latest-sevis-by-the-numbers-report

Thoms, J. C. (2008). Ethical integrity in leadership and organizational moral culture. Leadership, 4(4), 419-442. http://doi.org/10.1177/1742715008095189

Treviño, L. K., Brown, M., & Hartman, L. P. (2003). A qualitative investigation of perceived executive ethical leadership: Perceptions from inside and outside the executive suite. Human relations, 56(1), 5-37. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726703056001448

Tsui, J., & Windsor, C. (2001). Some cross-cultural evidence on ethical reasoning. Journal of Business Ethics, 31(2), 143-150. http://doi.org/10.1023/A:1010727320265

Weaver, G. R., Reynolds, S. J., & Brown, M. E. (2014). Moral intuition: Connecting current knowledge to future organizational research and practice. Journal of Management, 40(1), 100-129. http://doi.org/10.1177/0149206313511272

Weiming, T. (2014). The context of dialogue. In Asante, M., K., Miike, Y., & Yin, J. (Eds.). (2014). The Global intercultural communication reader (2nd ed.). Taylor & Francis.

Wendt, J. M. (2016). Economic fluctuations and the determinants of international student enrollment patterns in U.S. colleges and universities (Order No. 10167915) [Doctoral dissertation, Claremont Graduate University]. ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global.

Comments