Chapter And Authors Information

Content

Abstract

The gender disparities in Pakistan and the paucity of inclusive spaces to discuss issues concerning women, as well as the state’s negligence on policy reforms is resulting in resistance politics from women’s and gender minorities. In recent years, there has been a growing movement for independent yet collective actions to reclaim these shrinking spaces. A new wave of feminist activism for women’s rights is emerging as the Aurat[1] March, a socio-political street demonstration of women demanding their basic rights. This feminist activism is relatively independent from the existing work on women’s issues because of its eminence and orientation. Although women’s protests have existed in Pakistan, a street demonstration across different cities of this scale and nature indicates that feminism in Pakistan is becoming more akin to uprising. This paper investigates the mass mobilization for the Aurat March by looking at the dynamics, changes, and trends in women’s movements and feminist activism that paved the way for it. It particularly investigates and critically analyzes the emergence of contemporary feminist activism, social media feminism, and intergenerational collaboration for organizing large-scale street demonstrations. The study also attempts to discover contributing factors in determining the March’s popularity in terms of visibility, outreach, and attendance. By asking questions about the extent of generational collaboration between feminist activists and existing women’s organizations, this investigation engages questions the extent to which generational convergence contributed to the mass mobilization of the Aurat March, with implications for future action. Furthermore, I argue that despite scholarly assertions regarding feminist waves and real-world generational philosophical and political difference, collaboration for social change occurs.

Keywords

Feminist Movements, Gender Equality, Feminism and Politics, South Asian Feminism, Fourth-Wave Feminism, Social Media and Feminism

Introduction

Women in Pakistan continue to face discrimination in terms of equal access to rights and resources. Pakistan’s ranking for gender equality remains one of the lowest in the world.[2] Primarily, women’s issues in Pakistan center around access to quality education, healthcare, safe working conditions, and political participation. More broadly, issues that impact women’s lives intersect with citizenship struggles, fundamentalist movements, and social/sexual identities.

In response to the issues concerning women, various women-led forums, networks, and NGOs formed through the 1980s and 1990s. After the period of Islamization and imposition of discriminatory laws during General Zia’s regime, women defied these laws, dictatorship, and their subordination through street protests and the formation of women’s organizations to fight against state oppression.

Over the last few years, the government of Pakistan has taken a number of steps to promote women’s status; however, women still continue to face discrimination in accessing basic rights. Pakistan is witnessing a new wave of activism for women’s rights emerging as the Aurat March (Saigol & Chaudhary, 2020).

Pakistan observed an emergence of a feminist movement in March 2018 that has grown over the course of three years. Women leave their homes on International Women’s Day, to take their demands to the streets. This March brought together thousands of people from diverse backgrounds and women’s rights collectives to march against various forms of injustices. These marches were conducted in major cities in Pakistan including, Karachi, Lahore, and Islamabad, as well as other smaller cities like Sukkur, Hyderabad, Quetta, Peshawer, and Faisalabad in later years. They reached the mass population far across the country through various TV channels, social media, and newspapers (Hasan, 2018).

In Lahore, for example, the march started at Hamdard Hall, Lytton Road towards Mall Road, where hundreds of people including men and women walked in solidarity carrying creative placards that depicted messages of misogyny, sexism, domestic violence, day-to-day inequality, gender-roles. The protests featured major issues concerning women such as the right to education, wage gaps, child marriages, rape and assault, honour killings, labour rights, reproductive rights, and political representation for women. The agenda of these marches also highlighted coerced disappearances by the state, untiring efforts and struggle of the working class against land eviction, and promises to ensure their security in future. The agenda of the “Aurat March” was to speak for the basic rights of women and the transgender community and working-class women, but, more importantly, it focused on the emancipation of marginalized communities from state oppression. Women fighting for their rights through such personal and collective initiatives have their concerns regarding how the space for free speech and dissent has been shrinking in the public sphere. Over the past few years, feminist activists have created an online space for themselves; however, that online space needs to be supported by street protest to make their voices heard and gain greater visibility. Since Pakistan’s independence, women struggling for their rights have dispersed into smaller individual pockets with different agendas. Scholars argue that there has been a generational gap between feminists that can be eradicated through such initiatives and protests, where women of all ages, social classes, and ethnic and cultural backgrounds can come together to raise their voices against oppression and injustice (Nayeem, 2018).

Methodology

A qualitative research approach is best suited to facilitate “verbal description of real-life situations” (Silverman, 2014). This provided valuable insight into the experiences of research participants regarding the Aurat March. Within the qualitative paradigm, a case study method has been used for this research to get a deeper understanding of the March. As Creswell (2013) mentions, that broader understanding of a case emerges through this collection method in which the researcher explains aspects, history, chronological events, and organization of the activities of the case. Cases are located in specific contexts bounded by time and activity, and researchers collect detailed data using a variety of data collection procedures over a sustained period of time (Stake, 1995, cited in Creswell, 2014). This type of case study is used to explore those situations in which the intervention being evaluated has no clear, single set of outcomes and is also used to describe an intervention or phenomenon in the real-life context in which it occurred (Yin, 2003, cited in Baxter & Jack, 2008).

Sampling and Participants

Different approaches were used to access the Aurat March organizers for interviews. For example, some of the key organizers of the event were contacted through email and a few others were contacted through the official social media accounts of the Aurat March. Further, snowball and referral chain methods were used, in which some of the key organizers connected me with their peers and feminist circles.

The organizers added me to the Aurat Azadi March Whatsapp group of the Islamabad chapter, which has more than a hundred volunteers. Participants were identified from this group through an open invitation to participate in the research study. Personal messages were received from the volunteers who then were contacted to schedule one-on-one interviews. In total, 20 participants were approached from three major cities in Pakistan, including Karachi, Lahore, and Islamabad, for in-depth interviews. Out of 20, participants, 15 participants agreed and could take the time to participate in the research. Fifteen in-depth Skype and Zoom interviews were conducted with three groups of people including activists, participants who attended the march, and organizers, i.e., organizing committee members.

Data Collection Tools

Three semi-structured questionnaires with closed and open-ended questions, including similar and interlinking questions, were developed for three different groups of research participants. One interview questionnaire was developed for the organizers (committee members), one for the activists, and one for the participants to get insights into participant observations of the march. However, the questionnaires were not strictly followed so as not to not interrupt the respondents while they answered questions, resulting in interlinking questions being answered before being asked. Moreover, the participants were welcomed to share their opinions and experiences of the march.

Data Analysis

Verbatim transcription for all the interviews was done while identifying emerging patterns and themes in the light of the questions and literature review conducted earlier. The collected data was analyzed repeatedly while keeping the research questions and literature in consideration to identify findings and themes. The interview questionnaire was very detailed and lengthy; however, major categories of themes were developed by merging some of the sub-questions into broader themes.

Feminism in Pakistan: Past and Present

In post-colonial and Muslim nation-states, it is difficult to look at equality for women merely as a human rights issue due to various socio-cultural and religious barriers in women’s development. Women are not only fighting for their basic rights but also for an equal place in a patriarchal Muslim society (Saigol, 2016). Women’s organizations such as the Women’s Action Forum (WAF), which was founded in 1981, have an autonomous approach in fighting for women’s rights in Pakistan (Khan, 2018). Mumtaz (2005) discusses that WAF was established to oppose the Hudood Ordinance[3] that affected and marginalized women. The Hudood Ordinance also affected judicial procedures where women’s evidence was excluded, violating the rights of women by hampering their participation in court proceedings. Therefore, collective and systematic action was required to gather women on a platform to fight against the state’s oppressive discrimination (Saigol, 2016).

The women’s movements in Pakistan have their origins in various rights-based movements, hence feminist perspectives are likely to be integrated with various other social justice issues. The low political participation of women paired with low socio-economic power positioned women as weaker citizens and passive receivers after the Islamization of laws in Zia-ul-Haq’s period (Saigol, 2016). Pakistan as a postcolonial state has politicized religion, hindering the development of women’s agency in various ways since 1947. It has also created constraints for women in public and private affairs through the Islamization of laws, particularly, in General Zia-ul-Haq’s regime. The legal alterations in the name of Islam have resulted in issues of women’s freedom, identity, and self-expression. Even though Pakistan claims to uphold equal rights for women according to Article 25 of the constitution of Pakistan, the right remains an unpracticed theory as the majority of women are marginalized and considered weak subjects within the larger Pakistani community.

Women’s organizations such as WAF resisted and challenged the existing government regimes and struggled for approximately ten years, representing women’s voices in Pakistan. WAF’s agenda included women’s right to work, an indictment of customary practices that violated women’s rights, and a call for women’s political participation. The discourses also highlighted issues of honor killing, rape, violence against women (VAW), and rigid customs. In 1988, following the selection of Benazir Bhutto (the first female prime minister of Pakistan), other women’s organizations with different strategies started to form that influenced government and policy decisions through dialogue and political engagement. Women’s advocacy campaigns also expanded through media and global alliances. By the mid-1990s, feminist advocacy and women’s organizations in Pakistan lacked autonomy in their struggle with different agendas (Saigol, 2016; Mumtaz, 2005). However, the long struggle of women’s advocacy campaigns resulted in socio-political shifts by the early to mid-2000s. Women were provided political representation by the allocation of 33% of seats in government bodies, 17% in the parliament, and a 5% quota for government jobs.

In the past few years, women’s advocacy campaigns have also been visible in the media. The culturally sensitive issues that were once taboo have also started to be discussed publicly. The Hudood ordinances that had been a major focus of women’s organizations have also been undergoing review since 2003 for amendments (Mumtaz, 2005). Women have been fighting against such systemic oppression constantly in response to repressive religious and national regimes through active resistance. They have also adopted various methods of resistance over the years in form of protests such as the Aurat March, digital/street art, women-led sports initiatives, and music. Similarly, Shaheed (2019) discusses women’s participation in Pakistan in both the ways that contribute to policy-making through women’s organizations such as WAF and Hum Aurtein[4] and young activists who use new media to contribute to change. Shaheed argues that to maintain the sustainability of any women’s movement, that movement should be familiar with the dynamics of the country’s governance and politics. Despite being affected by social actors every day, the new wave of feminist activists does not necessarily confront the state through political participation. Rather, it finds ways for immediate action through different channels. These innovative actions tend to reshape gender dynamics in everyday practices that may challenge existing laws in the country.

However, it is problematic to assume that the actions of feminist activists have a long-lasting impact that leads to major changes in the laws and policies for women’s rights unless supported by the government and non-profit organizations in Pakistan. Women’s movements, both led by the older generation of feminists and younger feminists, require solidarity, organizational management, and unanimous action to change state laws and policies in Pakistan. Women will be able to voice their opinions and empower themselves given the opportunities to connect with each other regardless of their class, age, or physical location (Shaheed, 2019). Saigol (2016) also argues that the lack of solidarity of feminists and women’s organizations in movements lacks inclusiveness and unity amongst the different types of feminists.

Feminist scholars provide historical narratives of women’s struggles since its independence. These narratives locate women’s issues in the Pakistani context while posing questions regarding the widespread impact of social movements, engagement of younger activists, and how to tackle deep-rooted patriarchal systems (Mumtaz 2005, Rehman 2017).

Social media and the grassroots feminist activism in Pakistan are responding and reacting to issues concerning women and non-binary individuals who come forth to share on such online social media platforms. The digital presence of activists on various social media platforms for feminist collective action (such as “Girls at Dhabas[5],” “Hamara Internet Project,” “The Feminist Collective” (TCF), and the Aurat March’s online campaigns to bring about legal reforms) is one of the major indicators of how the internet is being used as a strategic tool for organizing protests, mobilizing groups and individuals, and providing a platform for initiating dialogue (Khan, 2018). Through these platforms, feminists across borders aim to share their stories and overcome the social, cultural, and religious stigmas attached to women in public spaces.

However, despite the apparent benefits of a social media presence and freedom of expression, there also come many challenges that need to be sensitively treated. The women sharing their stories online have been attacked, received death threats, or have even disappeared. These feminist movements have been looked down upon, accused of being elitist, and thought to be aimed more at urban populations rather than the public (Rehman, 2017).

Findings and Analysis

This section discusses findings of the study and analysis categorized in main themes and subthemes.

Origins of the Aurat March

Social movements have been conventionally seen as a result of a more organized form of collective behavior and actions that involve both movements of personal struggle for change and struggles for institutional change, such as legal reforms, structural changes, and changes in political power (Jenkins, 1983). Social movement organizations constitute crucial building blocks for mobilizing social change; however, there are other informal structures and elements that also directly contribute to the cause, i.e., kinship and friendship networks, informal networks among activists, movement communities, and formal host organizations, which contribute to the process of mobilization for collective action (Kriesi & Wisler, 1996). In the context of the Aurat March in Pakistan, a similar theory and praxis is evident. Interviews with women from diverse groups and members of feminist collectives working in various cities across Pakistan revealed that there are varying perspectives and approaches in organizing the Aurat March and different strategies for mobilization. Moreover, women work collective as well as in different capacities on organizing committees to make the march possible. Interviews reveal that the Aurat March and Aurat Azadi March have different characteristics in terms of approaches towards fighting against issues concerning women; however, they stand in solidarity on International Women’s Day on the 8th of March every year.

Moneeza Ahmed, one of the organizing committee members of the Karachi Aurat March, who has been affiliated with the development sector and is also part of The Lawyer’s Movement and Missing Persons Movement in Pakistan, shared that she was one of the founding members of the Aurat March in Karachi. Although she believes that they did not create the bifurcation within the committee. There has been scattered feminist work that was initiated by collectives and NGOs. Hence, bringing everyone on one platform was their mandate for the march originally. Questions regarding feminist values, gender equality, and feminist values connecting to the state’s policies had not been answered before. I believed that this kind of work is not being done as much and women’s organizations, such as WAF, were more focused on institutional change, but the connection to communities across, say, working or middle class, was not there as such.

A lot of us would thirst for something which was more connected to people at grassroots and also something where we show a political force or a feminist power. I think at the back of our minds international women’s marches were there even though we were not influenced by western feminism but the idea that triggered in our minds was a women’s only march in Pakistan. (Interview with Moneeza Ahmed, December 12th, 2020)

Another key organizer mentioned that the first organizers of the march did not want to label it as an NGO initiative and wished to start an inclusive platform for women that would include women and trans-women who identify as women, where nobody is labeling anyone or is being associated with any organization. They started with their own platform of “Hum Aurtein” (We the Women), which was not a registered collective but a title given to the first organizing committee of the Aurat March in Karachi.

We wanted a platform which politicizes the woman question in Pakistan. So, then we created the organizing committee, it was not only WAF members but women from different groups/collectives and even individuals who came together with one agenda in mind to organize the march. (Interview with Qurat Mirza, Organizing Committee Karachi, December 8th, 2020)

Formation of the Organizing Committees

Findings revealed that there was no formal structure to the committees. Rather, it was more inclusive and non-hierarchical, open to women of all ages and backgrounds for collective action.

One of my friends, who is a feminist, approached me to get students involved in the outreach campaigns – that sounded really exciting to me because it was the first time, I think, I had seen groups wanting to engage with university students about feminism, and specifically articulating it as feminism. And then from there, things snowballed, and they asked for volunteers and help to martial the crowd. I think it gave the students an opportunity to engage with other feminists. The year after (in 2019), I was asked to be on the organizing committee. I have been involved more in fundraising and then, of course, I did quite a bit of work around planning and mobilizing people – and volunteering on the day of for security and supporting the organizers. (Interview with Dr. Shama Dossa, Organizing Committee Karachi, December 7th, 2020)

Characteristics and Structure of the Marches

From the interviews with organizing members of different cities, it was revealed that no particular organization can be accredited for arranging the annual marches across Pakistan. Different cities organized marches on International Women’s Day in 2018 across Pakistan, e.g., Karachi, Lahore, and Islamabad. However, in Islamabad the march began under the title of the “Aurat Azadi March” (Women’s Freedom March) and was initiated by the Women’s Democratic Front (WDF) as the foundation congress, where they decided to make a federal structure of the units in different provinces of Pakistan. WDF also decided to issue their own manifesto on the day; however, they believe that they have held several conferences in different provinces before. Speaking to the founding president of WDF Ismat Shahjahan, it was revealed that the ideology and characteristics of the Aurat Azadi March are different from Aurat Marches held annually in Karachi and Lahore.

So, we constituted Aurat Azadi March (Women’s Freedom March) in Islamabad and over the course of three years we have co-organized Aurat Marches across different cities (Karachi, Lahore, Sukkur, etc.). However, Auart Azadi March is solely organized in Islamabad by the Women’s Democratic Front (WDF). In 2019, we collaborated with the Women’s Action Forum (WAF) to organize the march in Hyderabad, Sindh. In Peshawer, Quetta, Islamabad, and Faisalabad, marches were organized from our platform. AAM has a socialist feminist orientation and Aurat March was held in two major cities (Karachi and Lahore), but we organize marches in different cities such as in Peshawar and Quetta (Balochistan) as well. We do invite people who are a part of leftist political parties and women’s organizations—for instance, in Islamabad WAF joins us in the organization of the march. So, Aurat Azadi March is an ongoing struggle, but Aurat March is an annual event which we carry out collectively. There are various arrangements, and it is contentious to say that everywhere the organization is the same. (Interview with Ismat Shahjahan, November 28th, 2020)

WDF openly identifies as an anti-capitalist, anti-feudalist, anti-religious feminist movement. It brings in the class perspective, where different feminist individuals and groups gather for the Aurat March and stand in solidarity, a beautiful development as far as the feminist resistance is concerned in Pakistan. It is transitioning towards a movement in which everyone has a voice. Similarly, another young member of the AM Organizing Committee Karachi Sana Rizwan shared her views about different approaches and cross-collaboration between committees of the marches across Pakistan:

It is always politics to try to have a united front. The membership in different cities varies because in Islamabad you find that there is a heavy WDF membership. Lahore may have different types of feminists, etc. So, every Organizing Committee has different leanings and alliances, but we have the same politics. So, it’s not like everyone must check in and share what their plan is. It just happens like an organic conversation, honestly. (Interview with Sana Rizwan, Organizing Committee Karachi, December 8th, 2020)

During the interviews, respondents shared their differing views about the organizational structures of the committees. Discussing the structure and nature of the Aurat Azadi March in Islamabad, Ismat Shahjahan stated:

There is no structure or hierarchy in the organizing committee—we all work according to our capacities. What is important to be understood here is that for us Aurat Azadi March is a political activity not an organization. (Interview with Ismat Shahjahan, Organizing Committee Islamabad, November 28th, 2020)

Similarly, Nayab Gohar, an organizing committee member from Lahore shared:

Everyone calls themselves a volunteer and contributes according to their strengths. Such as, I do a lot of media and TV related things, some people do mass mobilization, and some do research. I would officially not represent Aurat March, I will just talk from a feminist and women’s activist point of view. I have been involved in these campaigns since high school and with Aurat March for the last year and half. I run an organization which focuses on women’s rights, and it’s been three years [since] running this organization. (Interview Nayab Gohar, November 20th, 2020)

The participants also mentioned that there is not a structured criterion to participate in the Aurat March. The committee gives out an open call every year on social media platforms; it is an entirely voluntary process. To be a part of the organizing committee people have to show commitment by joining the initial meetings. The open calls are announced three or four months prior to the march, but there is no strictness about not attending meetings physically, as it is a voluntary action. However, people who sign up but do not wish to volunteer are then removed from the organizing group due to security and privacy concerns. Discussing the contributions and roles of committee members, Sana Rizwan, an organizing committee member responded:

A lot of people contribute in different ways. Sometimes it is a very small contribution, like someone may just be doing that one thing that’s required for one moment, maybe it’s hosting a meeting, you know, for example. So, we have different layers of organising, like, some people are very much to the core, some are to the periphery, and it’s very organic; it’s just about who can contribute to the work. Every year, new people also come in, and you know, there are no permanent members of the Organising Committee. Why there isn’t any permanent membership as such is that, some people have just been there from the start, and they continue to join every year, otherwise, it is fluid. (Interview with Sana Rizwan, Organizing Committee Karachi, December 8th, 2020)

Nayab Gohar further explained the outreach plan for the Aurat March committees:

In terms of membership, we put out calls to people who can work in any capacity, such as filmmaking or social media, but it’s still very loose, and there are no hierarchies as of now. I must also clarify that Islamabad, Karachi, and Lahore are separate. They have their own committees and volunteers. We all stand in solidarity with each other, but we are all different marches. (Interview Nayab Gohar, November 20th, 2020)

Sharing her experiences of forming the organizing committee, Tooba Syed, one of the organizing committee members in Islamabad shared:

I needed help with organizing the event in Islamabad, so I put out an open call and many women showed up, then we made committees while dividing tasks amongst organizers, such as, outreach plan, social media campaigns, etc. In 2020, we again made an open call, and 30 people showed up. Several women also joined existing organizations and women’s collectives. There are not constant members in the Islamabad committee as different people continuously move in and out of the city. But it has never been a big hurdle in organizing the March except new people are not very familiar with our work and they ask questions about things we already have done. Members of WAF are older, so they don’t do the groundwork but provide moral support. (Interview with Tooba Syed, December 1st, 2020)

The interviews revealed that the approaches for organizing the Aurat March varied across different cities; however, they stand in solidarity for the annual event on International Women’s Day on March 8th. There is, evidently, a debate about whether the Aurat March and Aurat Azadi March are united activities that come together on a single platform on 8th of March. However, most of the people believe that despite the differences in approaches and mobilization strategies, it can still be called a collective effort as they stand in solidarity in fighting for women’s rights and emancipation.

Mass Mobilization: Process, Strategies, Tools, and Platforms

People coming together voluntarily for a joint action has served as a major engine of social transformation throughout human history leading to profound changes in a wide variety of contexts and societies. History reflects that movements and groups have unified to overthrow and dismantle systems of oppression and subordination as observed in the case of indigenous people rebelling against colonialism (Almeida, 2019). For mass protests to transform into social movements requires continuous efforts, momentum, and commitment while developing collective identities and a common agenda for a cause. A social movement also depends on resource sharing and network building through which individuals and organizations collaborate for a common aim or agenda (Zhu et al., 2016).

The interviews with the Aurat March organizers reflect that there is a voluntary mobilization process and collaboration which continues for months before the marches. Mass mobilization is carried out through different approaches, strategies, and platforms, including social media campaigns, informal meetings, study circles, street art, utilization of Whatsapp for logistics, and community outreach. For instance, in Karachi the mobilization started with conversations on a smaller scale in their respective circles and other feminists in mid-January 2018, and then expanded:

We reached out to the communities, lady health workers, teachers’ associations then we started having bigger meetings, so we formed what we call an organizing committee. And then we wrote a purpose/ideology statement for the march initially that we would read in the meetings, and everybody would vote on it. And I think it was really organic the way we organized, and we did not expect the kind of impact it had. I think there was a lot of hunger basically across cities which somehow motivated women in different cities to organize marches. We thought we would get like 1,000-1,500 people but approximately 5,000 people came out for the march, which built rapport and was felt across the country. (Interview with Moneeza Ahmed, December 12th, 2020)

On the other hand, organizers in Islamabad, mainly consisting of WDF members, initially used different strategies and outreach plans for mobilization. Different organizations are invited through WDF to encourage them to do campaigns from their respective areas. The Aurat Azadi March social media outlets are used, including the Aurat Azadi March Whatsapp group, which has more than a hundred members that volunteer for mobilization:

We operate differently than the other cities—we are part of the left tradition which has historically been there even before the independence of Pakistan. It is a global culture in which these organizations work unitedly. So, historically we don’t have to invent any network the way Aurat March organizers might do in Karachi and Lahore. We have our united groups and mechanisms in place. We have progressive leftist parties that support us in mobilization. Even for security purposes during the march—our volunteers ensure the safety of the participants. (Interview with Ismat Shahjahan, November 28th, 2020)

Mobilization and Outreach through Art Campaigns, Social Media, and Community Mobilization

Various mass mobilization and outreach strategies were used for the Aurat March in Lahore, including mixed methods and strategies for outreach. Leading up to the protest day, volunteers of the committees visit universities and other public spaces to explain their manifesto that are then followed up with meetings. Community outreach and mobilization is another strategy used by the organizing committee by arranging meetings with the representatives and members of the community and domestic worker unions, where collective action already exists, to raise awareness regarding women’s issues and to invite people to participate in the protests:

This year (2020) after the Aurat March, we went back to a few communities who showed up on the protest day. We also hold meetings with existing groups such as, health workers and teachers’ unions, spaces that might not explicitly be feminist but groups where women have done some sort of organizing. And then also a combination of things in online spaces and traditional media to make open calls for people to show up. (Interview with Shmyla Khan, Organizing Committee Lahore, December 9th, 2020)

An alternative or additional medium used for mass mobilization for the marches across different cities is creating artwork. Although using artwork for campaigns is not a new process, the creativity of young artists, both digital and traditional, is new in the context of Pakistan. Artwork created by young artists for the Aurat March promotes and accelerates the process of social movement. Furthermore, it has highlighted the activities of women’s activism. Upon asking about the role of artwork and digital illustrations for raising awareness and mass mobilization for the Aurat March, a young artist, Shehzil Malik shared

the Aurat March posters as well a series of artwork on “Mera Jism Meri Marzi” (My body, My choice). I made posters as a call to action and to bring visibility to the dire state of women’s rights in this country. In 2020, we issued an open call for all women artists in the country to contribute their art and words for the march, and the response was amazing. (Interview with Shehzil Malik, Artist, October 30th, 2020)

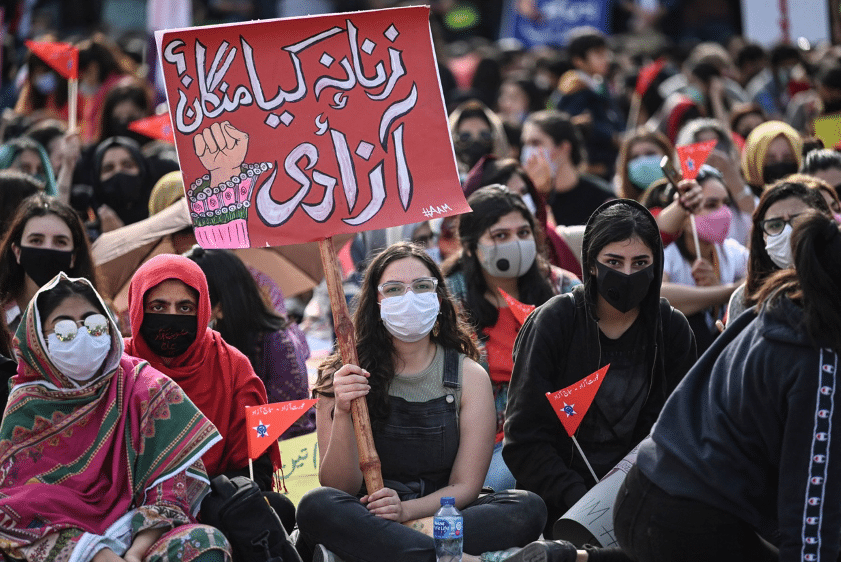

Figure 2.1. Mobilization and outreach through artwork

Source: http://www.shehzil.com/portfolio/aurat-march/

Shehzil further hopes that the posters created by artists had an impact on the visibility of the marches. She also shared that the posters were available free to download from her website and were used to help in outreach efforts, to explain the manifesto, and they were pasted across the streets in various cities. They were also discussed in the local and international press.

Aziza Ahmed, an artist from Karachi who creates artwork for AM, shared that the posters, both digitally and in hardcopy, that are disseminated for outreach to help raise awareness regarding the Aurat March. It also helps in the process of community mobilization, while bringing it to the public’s attention and creating dialogue on social media:

I think the artwork that is created for Aurat Marches has definitely helped in its visibility. Because it’s putting the message out there. So, every year when I make the poster, I make it with this intention of what I want to visualize for the Aurat March and what I want people to respond to when they think about the march. (Interview with Aziza Ahmad, December 4th, 2020)

Generational Differences and Collaboration

The views of the participants varied regarding prevailing generational differences of activism between older and younger women. Upon asking about the generational differences and extent of collaboration among women in terms of how they raise or discuss women’s issues in Pakistan, Dr. Shama Dossa elucidated:

I don’t think it’s two generations. I think that’s problematic. First of all, I argue there’s multicultural and multigenerational activism. And I would see myself in the middle. Feminism in Pakistan has gone through multiple stages, and it has been dependent on the contexts. And as context has changed and evolved, so have spaces and actors as well. (Interview with Shama Dossa, Organizing Committee Karachi, December 7th, 2020)

On the other hand, Nayab Gohar Jan, one of the organizing committee members from Lahore mentioned in her interview that there is a generation gap between the older and younger women in how they do activism and discuss women’s issues. However, it does not hinder their activism. She further stated that if there is intergenerational dialogue and engagement, that gap can also be filled:

Both the generations discuss women’s issues differently. For example, there are issues that are taboo to talk about like menstrual hygiene, reproductive and sexual health, mobility, clothing, even sexual violence. So, the young generation is a bit braver than the earlier generation. There is always a generational difference; there is no reason why it is there. Obviously, people who are 30 years older than you will have different ideologies. I think women’s rights have come very far; the previous generation was so used to accepting the status quo that they find it odd that younger generations complain about things they used to accept and found normal. But I don’t really think it impacts activism, unless and until the older generation will actively hinder us from doing something, but generational difference is normal and has always been there. (Interview with Nayab Gohar, Organizing Committee Lahore, November 18th, 2020)

Discussing the intergenerational engagement and dialogue, Ayesha Khan shared that there is a fear of dissent and a fear of exclusion from the existing women’s organizations in the younger generation due to different ideologies and systematic activism in the past. However, she also shared that new platforms are being used to encourage dialogue across different age groups of women:

I think there is dialogue and engagement. It’s not always harmonious, but there is a lot of discussion. There was a feminist convening at (Shirkat Gah[1]) in Lahore last year (2019) which was useful in indulging in conversation. It helped to understand each other’s positions. The whole mobilization around the marches, debates, the rejection and anger that younger feminists feel from the older, it all came out in the open, and I think it was fruitful and useful. (Interview with Ayesha Khan, November 19th, 2020)

On the contrary, Ismat Shah Jahan believes that the generational gap does not exist; rather, a class gap is prevalent, and each generation has its own differences. She believes that the main difference that emerged recently is that after the information revolution, young feminists found space on social media that is safer, but what matters the most is street protest. Social media activism always requires street demonstration to create an impact:

I believe that there are fringes on both sides of generations as some women from the younger generation are more conscious, and they have started interacting more with the older generation where necessary. While some young women are critical of the roles of the older generation and do not wish to engage or collaborate with them at all. They do their activism on social media independently. (Interview with Afiya S. Zia, December 3rd, 2020)

Contributing Factors for Aurat March’s Popularity

From the interviews it was observed that various factors have contributed to the popularity of the Aurat March. Furthermore, the responses of gender and political activists across Pakistan reveal that the emerging issues of women in Pakistan, such as, rape and murder cases, are increasing day by day. Women and children are not safe, and Pakistan has witnessed a new wave of sexual violence and patriarchal crisis that had made its way into the society:

The general public is concerned because the current situations are not favorable for women and this resistance has also emerged from their frustration. For instance, we gave a call for protest against rape cases with one day’s notice; approximately 2,500-3,000 people showed up in Islamabad. So, it is about public sentiment. For us this resistance is not a one-day activity, but we organize activities throughout the year. We arrange study circles; we go to different areas of Pakistan where we have our own units and systems. This organizing, campaigning, and public outrage have made it a success. The conventional media has spoken against us, but it has actually helped us at their own cost. The more they go on conservatism lines, the more people support Aurat Azadi March and other feminist groups. (Interview with Ismat Shahjahan, Organizing Committee Islamabad, November 28th, 2020)

Figure 2.2. The placard reads “What do women want? Freedom.”

Source: Getty Images

She further mentioned that WDF believes in women’s emancipation and fights against “patriarchal violence.” And to dismantle patriarchal structure, it is crucial to bring it to the public’s attention. One of the reasons why WDF decided to call the march the “Aurat Azadi March” (Women’s Freedom March) in Islamabad was to change the socio-political narrative of feminism. Their ideologies revolve around politicizing the woman question without which changing the socio-political culture or bringing in legal reforms in Pakistan would be a challenge. Furthermore, she stated that class exploitation, national oppression, patriarchy, capitalism, and religious fundamentalism are intertwined, and people need to talk about changing the whole system.

A gender activist, Laila, shares her views about expanding the mobilization for the march to working-class women for the march to be a success:

While organizing the march what people don’t really realize is that there is an effort by the committee to reach out to working-class women, going to working-class neighborhoods and mobilizing and understanding their concerns, but is it not enough—there’s always room for more. The Aurat March has been criticized for being very sort of upper-middle class. And I think the criticism is not entirely fair. Although there are some elements of it. I don’t think that is entirely fair. Because there have been efforts to reach out to different classes of women. (Interview with Laila, Organizing Committee Karachi, December 9th, 2020)

Figure 2.3. Community mobilization prior to the Aurat March

Source: http://www.shehzil.com/portfolio/aurat-march/

Another factor in the Aurat March’s popularity is the potential and strength of social media; however, it comes with its own limitations and drawbacks. Social media “activism” is individualized, does not really have space for discussion, debate, or healthy disagreement, and often operates in echo chambers. The benefits of social media organizing has its expanded outreach and the number of women who have been able to connect to each other virtually when patriarchal norms discourage them from gathering publicly. Women’s organizations are also using social media platforms for their activism. There are also collectives that use different solely use social media campaigns. It is not an alternative for activism, rather a mode of communication or another option that enhances visibility. However, the women’s organizations that had been there for decades have a niche audience. Women who do not wish to join these can still be vocal about what they think, what they want, and what they’re willing to do. They can also find a community within their online circle.

Interviews revealed that the skills of the younger generation also contributed to raising awareness about the Aurat March, which included but were not limited to, artwork, discussions, and social media campaigns using hashtags, theatre performances, poetry, etc. When asked about contributing factors in popularity, Tooba Syed responded:

A younger generation brings in different skills, such as increased knowledge and internet access. They are also aware of feminist struggles because they read literature. Their awareness has increased more recently about gender activism and feminism. And due to social media, the march has been successful. In the last 20 years, issues of women in Pakistan were not highlighted as such, and they hardly made it to the international level. Domestic violence is still not considered a crime in Pakistan except for one province. And increased cases of harassment and other forms of violence that women face have resulted in the popularity of Aurat March as women can relate to their struggles. Given the oppression, especially within the household, many girls could relate, and this also became a factor for the mobilization. (Interview with Tooba Syed, December 1st, 2020)

Nayab Gohar also reiterated that in this age of social media, nothing really remains small especially when it is so thought provoking. Younger women are vocal, and they bring in the power of social media, while the older generation offers institutional strength. She considers the mobilization of the younger generation as one of the contributing factors of the Aurat March’s success because of new skills such as social media use, creative approaches, and new perspectives on the march. Younger generations of women are also more outspoken about highlighting themes such as intersectionality, class, gender, ethnicity, and sexuality:

Social media played a pivotal role both in the controversies that it had created and by giving us a voice. Mainstream media did not cover it in the last two years, but this year because of social media, it’s viral. We conveyed our message through social media and mobilized our opposition. I 100% think that digital platforms have given us an opportunity to fight our battles online, a lot of our problems manifest online, such as rape threats, bullying, etc. It’s good that young women want to utilize social media for a good cause. (Interview Nayab Gohar, November 20th, 2020)

Afiya Zia sees that social media has been used for mass mobilization globally for the #metoo movement, and the impetus and the impulse for the inspiration for the march came from the global marches:

Social media was an important mobilizer and a successful tool in mobilizing people for the march. And it’s been successful in terms of its formative value, because it draws in people from different backgrounds, whether it’s curiosity or genuine interest. But I personally am not part of social media because I think it generalizes and blunts the specifics that are required in collective action. It doesn’t allow for conceptual clarity, and it has this very new liberal kind of hierarchical feature to it. I don’t subscribe to the idea of popularizing an issue which is important, circulating information quickly is also very important, but at the end of the day, I don’t think it contributes largely to collectivism. (Interview with Afiya S. Zia, December 3rd, 2020)

New Gender Activism

Categorizing gender activism in waves is contentious as there is an overlap, back and forth. It is also difficult to say at this point if this new activism is moving towards a sustainable and massive women’s movement. The movements in 1960s, as compared to the millennial politics, arguably brought major reforms and introduced cutting-edge rights as compared to other parts of the Muslim world. In fact, family laws in Pakistan are far more advanced than they were for Muslims in India:

I value [social media’s] contribution in bringing protests back onto the streets, bringing certain slogans, and bringing sexuality into the public discourse. These are very valuable contributions which other movements weren’t able to make. So, I’m not suggesting it hasn’t contributed anything unique. But its sustainability is a concern like it is for all of our movements. And what social media doesn’t allow is participation in person, instead you absorb a lot. Women can merge the two kinds of poles of their politics and priorities by learning from the mistakes or the successes of an older generation. Because they have legacies and institutional memories. (Interview with Afiya S. Zia, December 3rd, 2020)

On the contrary, the younger generation of women feel that they are living in the new wave:

I think we probably are in the new wave, it’s probably much more difficult to identify it once you are living in it. But, yeah, especially speaking to older feminists made me realize how the nature of this movement has changed. For instance, the use of online spaces, highlighting LGBTQ+ issues, and bringing them to public discourse despite cultural sensitivities and a combination of all these things have changed the dynamics of feminism in Pakistan. I believe we will become much more explicit over the years, in fact, I think that shift has already happened. (Interview with Shmyla Khan, Organizing Committee Lahore, December 9th, 2020).

Figure 2.4. Street demonstrations on the International Women’s Day, 2021

Source: pakobserver.net

Research findings revealed that the Aurat Marches across different cities in Pakistan have different characteristics and approaches; however, they stand in solidarity for the marches and coordinate with each other wherever necessary. One of the main organizers of the Aurat Azadi Marches in Islamabad is WDF that has its own extended networks and systems across different cities, including Sukkur, Quetta, Peshawer, and Hyderabad. Moreover, a new type of gender activism has surfaced in Pakistan that brings in social media feminist activism along with street protest. However, this new activism requires solidarity and coordination with the government and women’s organizations for it to be more effective and sustainable. The research findings also reveal that despite distinctive characteristics of organizing committees and women’s collectives across Pakistan, there is clearly a collaboration between older and younger generations of women for the Aurat March.

Conclusion, Implications, and Way Forward

Observing Pakistan’s feminist landscape and analyzing the research findings, it is evident that the Aurat Marches across different cities bring in various perspectives and approaches that may further contribute to socio-economic and socio-political shifts in Pakistan. It is contentious and difficult to say if feminism in Pakistan is transitioning towards a fourth wave; however, a new type of gender activism is emerging that is unconventional and relatively distinct from the existing organizational feminism. However, this new activism requires solidarity, systematic activism, and coordination with the state and existing women’s organizations for it to be more effective and sustainable.

Despite the distinctive characteristics of organizing committees and women’s collectives across Pakistan, there is clearly a convergence and collaboration between older and younger generations of women for the Aurat March. Due to this melding of two generations for the Aurat March, where they strengthen and transform each other while keeping their own ideologies and characters, something more massive has been initiated than previous feminist movements in Pakistan.

The collaboration and mass mobilization of younger generations of feminist activists add an entirely different type of visibility with the artwork, street demonstration, community mobilization, creative sloganism, and social media campaigns. The Aurat Marches would not have been successful without the support and coordination of the older generation of feminists who are also affiliated with established women’s organizations. The younger generation might be aware of using social media for campaigns and visibility; however, for collective action and on-the-ground activism, systematic feminist approaches and collaboration are necessary. Moreover, grassroot efforts and coordination with the state are also crucial, as the dynamics of street activism or protests are different. Although there have been massive feminist movements in the past that also contributed to legal reforms, annual protests of this nature and scale have never been witnessed before in Pakistan. This, moreover, indicates that during this collaboration many generations complement and strengthen each other as some have the organizational capacity and others have social media activism and innovative technical skills for visibility and creativity. And, in fact, from the convergence of this emerges a new type of feminist activism. Aurat March activism can be sustained and expanded through consistent discourse, building alliances with other feminist collectives, coordination with the government bodies, and lobbying for legal reforms.

[1] Aurat, the Urdu word for woman. The “Aurat March” (Women’s March) is an annually held women’s socio-political street protest organized across major cities in Pakistan.

[2] https://asiapacific.unwomen.org/en/countries/pakistan

[3] The Hudood Law was an imposition of Shari’a law into the Pakistani laws that states “conformity with the injunctions of Islam,” by enforcing punishments according to the Holy Quran and sunnah for zina (extramarital intercourse), qazf (false accusation of zina), theft, and consumption of alcohol. See further, http://www.pakistani.org/pakistan/legislation/zia_po_1979/ord7_1979.html.

[4] Originated in Karachi, “Hum Auratein” (We the Women), is a women’s collective that emerged as an organizing body of the Aurat March that conducts community outreach activities for women.

[5] “Girls at Dhabas” literally means, “Girls at Stalls.” Dhaba is a restaurant or a stop for truck drivers on highways mostly prominent in South Asia. The Dhaba trend has made its way to the urban sphere as well to reclaim women’s spaces in public.

[1] Shirkat

References

Almeida, P. (2019). Social Movements: The Structure of Collective Mobilization (1st ed.). University of California Press. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctvd1c7d7

Baxter, P., & Jack, S. (2008). Qualitative Case Study Methodology: Study Design and Implementation for Novice Researchers. NSUWorks. https://nsuworks.nova.edu/tqr/vol13/iss4/2/

Creswell, J. W. (2013). Qualitative Inquiry & Research Design: Choosing Among Five Approaches. Sage Publications.

Creswell, J. W. (2014). Research design: Qualitative, Quantitative and Mixed Methods Approaches (4th ed.). Sage Publications.

Hasan, S. (2018, March 6). Aurat March to be held on March 8. https://www.dawn.com/news/1393445

Jenkins, J. C. (1983). Resource mobilization theory and the study of social movements. Annual Review of Sociology, 9(1), 527–553. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.so.09.080183.002523

Khan, A. (2018). The women’s movement in Pakistan: Activism, Islam and Democracy. I.B. Tauris.

Kriesi, H., & Wisler, D. (1996). Social movements and direct democracy in Switzerland. European Journal of Political Research, 30(1), 19–40. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6765.1996.tb00666.x

Mumtaz, K. (2005). Advocacy for an end to poverty, inequality, and insecurity: Feminist social movements in Pakistan. Gender & Development, 13(3), 63–69. https://doi.org/10.1080/13552070512331332298

Nayeem, B. (2018, March 9). This is what women REALLY want: Aurat March Lahore issues a statement of demands. Daily Pakistan Global. https://en.dailypakistan.com.pk/09-Mar-2018/this-is-what-women-really-want-aurat-march-lahore-issues-a-statement-of-demands

Rehman, Z. (2017). Online Feminist Resistance in Pakistan. Sur - International Journal on Human Rights, 26. https://sur.conectas.org/en/online-feminist-resistance-in-pakistan/

Saigol, R. (2016). Feminism and the Women’s Movement in Pakistan Actors, Debates and Strategies. https://library.fes.de/pdf-files/bueros/pakistan/12453.pdf

Saigol, R., & Chaudhary, N. (2020). Contradictions and Ambiguities of Feminism in Pakistan. http://library.fes.de/pdf-files/bueros/pakistan/17334.pdf

Shaheed, F. (2019). The Women’s Movement in Pakistan: Challenges and Achievements. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/57a08b29ed915d3cfd000b92/Shaheed_Womensmovement.pdf

Silverman, D. (2014). Interpreting Qualitative Data (5th ed.). Sage Publications.

Zhu, Q., Skoric, M., & Shen, F. (2016). I shield myself from thee: Selective avoidance on social media during political protests. Political Communication, 34(1), 112–131. https://doi.org/10.1080/10584609.2016.1222471

Comments