Chapter And Authors Information

Content

Abstract

Teaching in virtual learning environment calls for different competencies, roles, and skills rather than teaching in a traditional classroom. Teachers need to spotlight on the integration between the teaching approach and how they assess and evaluate their students’ academic progress. Furthermore, teachers need a precise, focused, and continued online assessment method to measure their professional teaching key performance indicators. There is a lack of studies that measure the impact of technology acceptance on teachers attitudes to use online assessment tools to measure their students’ learning outcomes. The purpose of this study was to examine the impact of EFL teachers’ attitudes on using online assessment tools. One hundred fifty-six participants answered an attitude technology survey containing 15 questions about the ease of use, usefulness, and attitudes toward technology. A purposeful interview with 12 participants supported the result.

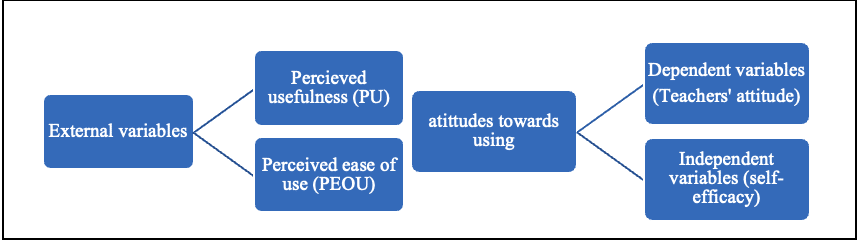

The researcher examined whether there was any connection between the independent variable (Self-efficacy) and the dependent variable (Teachers’ Attitude) and the external variables Perceived Usefulness (PU) and Perceived Ease of Use (PEOU). The study compared the survey’s means for each question and discovered that three had the highest means, indicating better attitudes, and five had the lowest three means, indicating attitudes toward technology and online testing that were worse. The findings indicated that the usefulness and usability of the online assessment tools would increase the likelihood that people would use them. However, the attitude toward perceived ease of use (PEOU) had an impact on the intention.

Keywords

Teacher-Efficacy, Self-Esteem, Technology Acceptance, Attitude

Introduction: Starting Point and Theoretical Background

Enhancing technology in education is the biggest challenge we face in the educational field. Digital technologies boost learning through information access, enhanced communication, and offering various opportunities for collaborative and self-directed learning. Ibrahim (2018) stated that effective use of technology encourages participation and collaboration between students and teachers in the teaching and learning process. ICT skills help in developing capable future-ready citizens. Since, the world faced a health crisis as COVID-19 has spread globally.

Consequently, the Saudi Ministry of Education moved to deliver online teaching for all stages of K-12 starting in Spring 2020. The more effective and successful transitions to online learning are highly influenced by the degree of teachers’ intention and acceptance of technology and the usefulness of the technological tools in the teaching process (Sulistiyaningsih et al., 2014). Therefore, it is crucial to examine the variables that affect the adoption and use of technology. There has been a growing debate on how effectively we can use technology tools to assess students through online learning to address the factors that affect the acceptance of the technology system in education.

Piaget’s (1936) epistemological concepts set out to explain how learners’s minds develop enabling them to adapt to the environment. Piaget’s theory of cognitive constructivism developed five basic cognitive conceptualizations to illustrate the development of human knowledge acquisition. The theory focused on the intellectual growth of the existing schema (knowledge), which happened to adapt to the current situation. A schema is a way of organizing distinct pieces of knowledge within the human mind each particular schema that an individual human has is a representation related to different aspects of the World objects abstractions concepts and actions (Carey et al., 2007).

Piaget envisioned five processes constantly working together to drive the progression of intellectual development. The transformation occurs through the process of schemas, assimilation, accommodation, equilibration, and disequilibrating. According to Piaget, people use assimilation to elucidate and develop new perceptions in their current understanding by fusing new experiences into old ones, which forces people to reconsider and assess what is essential.

On the other hand, accommodation happens when individuals change the existing schema (knowledge) or create a new one to incorporate new experiences better, while equilibrium is the relationship between an individual and the natural world (Byrney, 2008).

Assimilation is the process of integrating new experiences into already existing schemas without modification. Assimilation occurs continually as environmental information is taken in from the outside world and mapped onto existing schemas. Thus, assimilation accounts for significant quantitative developmental growth, but it does not account for changes in existing schemas. While the process of accommodation means the changes that occur and motivate learners to understand new information about their world. When the learners interpret new information and assimilate it successfully, they are in the state of equilibrium. On the other hand, when the learners cannot assimilate the information, they are in disequilibrium state (Barrouillet, 2015).

Piaget’s cognitive constructivism theory addressed how learning occurs and is facilitated through a relationship between cognitions (schemas) and behaviors (attitudes). Humans use their cognition in every part of their social lives. They use their mental activities of processing information and use that information in understanding and judgment (Cooke & Sheeran, 2004).

The bridge between cognitive learning theories and behaviorist learning theories is Bandura’s social cognitive learning theory (1960). The psychologist Albert Bandura developed the learning social cognitive theory that provides a framework for understanding how people actively shape and are shaped by their environment. The theory views people as active agents who influence and are influenced by their environment. The theory focused on the impact of self-efficacy on the production of behavior. People beliefs on the influence of their self-efficacy in repeating an observed behavior or not (Genc et al., 2016). The theory provides a framework for understanding the learning process in two ways: direct experience and observation of others. It focused on three key concepts: observational learning, which means people learn by active shape and are shaped by their environment. Observational learning is influenced by four processes: attention, retention, motor reproduction, reinforcement, and motivation (Nabavi, 2014). The second key concept is Triadic Reciprocal Determinism (TRD), where person, environment, and behavior are interwind and correlated together. An external physical environment influences internal factors like cognition, affecting a person’s behavior (Razmjoo & Movahed, 2009). Self-efficacy is the third key to Bandura’s social cognitive theory, which is defined as people beliefs in their abilities to perform something. Nabavi (2014) noted that individuals’ self-efficacy is a crucial internal factor in the Triadic Reciprocal Determinism relationship. It prolonged all sides of their lives, such as career choice, habits, and emotional regulation. According to Mohammadi and Isanejad (2018), the study of self-efficacy has considered a wide range of topics, including the connections between people’s perceptions of their own competence and internal cognitive processes.

However, Behroozizad et al. (2014) assumed that in education field, teachers’ self-efficacy plays a crucial role in gaining high job experience by challenging students and making them influential critical thinkers. Thus, the importance of teachers’ self-efficacy guided this explanatory research to address how teachers’ self-efficacy is an influential factor that significantly impacts teachers’ perceptions and attitudes towards the usefulness and ease of successful implementation of using technology to enhance their online teaching and facilitate their methods of assessing their students.

There has been an enormous increasing demand for using online learning in the past decade. English as a foreign language (EFL) has received considerable attention in online education. Soliman (2014) defined eLearning as delivering information, instruction, and communicating through digital devices with the intent of supporting learning. Nowadays, many technology-based learning opportunities influence teaching and learning EFL in an eLearning environment. Ramorola (2013) pointed out that distance eLearning is developed to meet diverse needs and attain learning objectives. It serves different levels of learners and educators. Online programs show benefits in developing English skills among ESL/EFL learners (Ramnarain & Hlatswayo, 2018). A vast amount of literature considered assessment as a critical component of learning. Assessment is a critical step in the eLearning process. Rastgoo and Namvar (2010) indicated online assessment as a component of the learning process with significant benefits over the usual face-to-face assessment. According to Reeves (2000), assessment in education has many purposes and principles that enable teachers to re-teach, move on, or change their teaching strategies. It determines whether or not the course met its learning objectives. Assessment affects many aspects of education, including students’ grades, placement, advancement, and curriculum instructional needs.

Nowadays, online assessment is a highly rising way of evaluation in distance learning. A comprehensive evaluation of the students’ abilities requires clear instructions, accessible tools, and accurate results to develop their abilities further. Bhagat and Spector (2015) indicated that formative assessment gives focused feedback to instructors and learners about how well learners understand information and acquire specific skills while a summative assessment is an analysis used to record and measure individuals’ accomplishments (Mohamadi, 2018). Cassady and Gridley (2005) asserted that the online summative assessment process bears clear and well-designed instructions to sustain a high level of accuracy and validity. Gulikers et al. (2004) declared the importance of designing a new authentic assessment modality in distance and online learning to accomplish educational outcomes. Miranda et al. (2019) pointed out various practical distance learning assessment tools to evaluate EFL learners’ levels and performance, such as flash meetings, skype, and TeamSpeak. Mohammadi and Isanejad (2016) noted the vast usefulness of electronic forums in developing and evaluating EFL learners’ writing skills. Gil et al. (2015) showed that the reliability and validity of online distance assessment are affected by different indicators such as faculty acceptance, tools modality, and time management. According to Ramnarain and Hlatswayo (2018), teachers face several dilemmas if they encounter new pedagogical approaches to education that affect their acceptance. Teachers’ experiences as language learners, their experiences of what works best, and their education principles, methods, and approaches establish practices of teachers’ source of beliefs.

Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) Framework

Technology reshaped education worldwide and directly impacted teachers and students’ relationships. Teachers who resist the inclusion of technology in their pedagogical practice end up stuck with outdated methods. On the other hand, teachers who can take advantage of the benefits of technology in the teaching and learning processes can act more attractively and innovatively with their students. Technology integration in education means when the students have access to various tools that match their task and provide them with the opportunity to build a more profound understanding (Scherer et al., 2019). Recently, technology is now in high demand as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic where online teaching and learning platforms have changed the education industry radically. Thus, teachers need to develop innovative pedagogies to redefine learning in a virtual space.

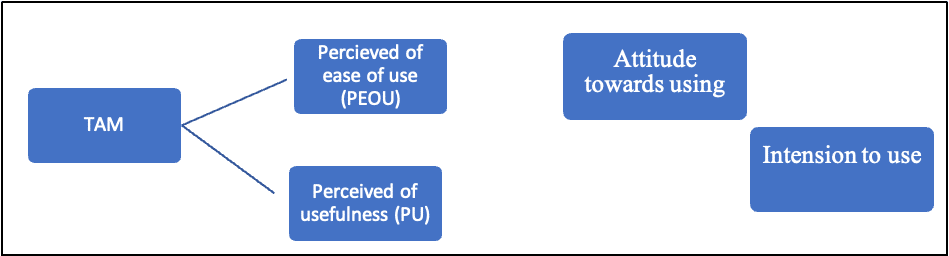

Davis (1986) developed the theory of reasoned action (TRA) by Fisher and Ajzen (1975). He introduced the technology acceptance model (TAM) to understand users’ perceptions and measure their motivation to use particular system. According to the technology acceptance model, a person’s behavioral intention (BI) to perform a given behavior determines whether or not they actually carry it out. A person’s attitude (A) and subjective norms (SN) both influence how they intend to behave (Silva & Dias, 2007). There are two core beliefs from the technology acceptance model (TAM): The term “perceived usefulness” (PU) describes a user’s subjective likelihood that utilizing a particular technology will improve his or her ability to perform their job. The dependent variable behavioral intention (BI), which is connected to the actual behavior, and the perceived ease-of-use (PEOU), which measures the extent to which a user anticipates using technology to be simple, are two terms used to describe these concepts (Scherer et al., 2019). The technology acceptance model described people’s beliefs and perceptions towards using technology, whether they use it because it is easy to use or valuable for what they want to do, such as calculating, accessing a quiz, and other issues related to their concerns (Pavlou, 2003). Therefore, perceived ease of use influenced perceived usefulness.

The question in this research is to what degree EFL teachers integrate technology into teaching and prefer online teaching. Liu et al. (2015) hypothesized that successful traditional teaching practices might not play a successful role in online teaching, which highlights the need to redefine other facets of education and encourage teachers to be more innovative to maximize students’ virtual learning opportunities. Albirini (2004) asserted that teachers’ rich experiences combined with designing exercises, real-world exploration, and varied assessments could benefit the learning progress in online practices.

The Role of Teacher’s Self-Efficacy, Belief, and Attitude in Technology Integration

Although integrating technology in EFL classrooms extensively impacts the educational process, some teachers struggle to use new technologies. Engen (2019) indicated that teachers’ digital technology competencies are influenced by many factors: personal characteristics, teachers’ attitudes, ICT competence, computer self-efficacy, and professional development. Numerous studies have shown that teachers will not be able to transform their classes, align with learning objectives, or incorporate technology into the curriculum if they do not believe in the use of digital technologies. The most critical attributes of teachers struggling with integrating technologies are teachers’ perception, attitude, and efficacy.

According to Bandura (1977), the social cognitive theory connected self-efficacy with motivation. Self-efficacy is the belief in one’s ability to achieve a goal. It is the assurance that one can achieve any goal they set their minds to by controlling their thoughts, feelings, and behaviors (Huang et al., 2018). Human behavior and self-efficacy are influenced by cognitive, motivational, affective, and selection processes (Montero et al., 2014). The phycologists drew significant differences between self-efficacy and self-esteem. The big difference between them is that self-efficacy is a feeling that depends upon performance, while self-esteem is an overall evaluation of the self. Efficacy is more specific, spontaneous, and it depends on a person’s ability to perform something at a particular point in time, while esteem is permanent (Pretz & Nelson, 2017). According to Genc et al. (2016), everything from psychological states to behavior or motivation can be affected by self-efficacy. People can identify their desired outcomes, changes they want to make, and achievements from their self-efficacy.

Therefore, individual self-efficacy is important when tackling challenges, goals, and tasks. Self-efficacy categorized individuals into two groups: people with a high level of self-efficacy and people with a weak level of self-efficacy. Strong commitments, the perception of difficult problems as tasks to be accomplished, and the development of deeper interests are all characteristics of people with high self-efficacy. In contrast, people who have a low sense of their own efficacy think they can’t handle difficult situations and tasks. They emphasize mistakes made by individuals and negative outcomes. They quickly lose faith in themselves and their own abilities (Phan & Locke, 2015).

According to Bandura’s social cognitive theory, to assess whether a person has a strong or weak sense of self-efficacy, there are four main sources of self-efficacy. All these four sources are interrelated and correlated: enactive attainment, vicarious experience, social modeling, and physiological factors (Raoofi et al., 2012). Vicarious or mastery of experiences means our self-efficacy will increase if we complete a task successfully. Social modeling refers to the idea that when we see people who resemble us succeed at a task, it strengthens our conviction that we can also accomplish the same tasks and be successful.

The third source is social persuasion where positive verbal encouragement from other people helps individuals to overcome their self-doubt and achieve their goals. The physiological reactions are the final source. When faced with difficult or challenging tasks, people learn how to reduce stress and improve their mood (Cubukcu, 2008). A person with low self-esteem may have a high sense of self-efficacy, meaning they may be overly critical and pessimistic of themselves but still believe they are quite capable in some areas (Chou et al., 2018). Pretz and Nelson (2017) noted that depending on teachers’ teaching experiences, self-efficacy beliefs, and goal orientations can play significant effects on their teaching practices.

According to Bandura, mastery activities are the best way to increase self-efficacy. The fundamental tenet of self-efficacy is that people feel much better about themselves when they believe their actions can have an impact on the course of a particular situation. They believe they oversee and have control over events in the world. Consequently, self-efficacy influences self-esteem because how people feel about themselves overall is greatly influenced by their confidence in their ability to perform well (Ucar & Bozkaya, 2016). Farah (2011) noted that gender in self-efficacy played a crucial role; males have higher self-efficacy in integrating technology rather than female. Gilakjani and Ahmadi (2011) hypothesized that teachers’ positive attitudes toward technology integration are an effective factor that reduced their anxiety and stress towards using technology.

In psychology, an attitude refers to an evaluation of a person formed by experience, emotions, or feelings about an object, person, group, event, or issue (Liu et al., 2017). Marza (2012) defined attitude as the state of mind, set of views, and thoughts regarding some topics. Teachers’ attitude is the characteristic and the affective, behavioral, and cognitive component of the teacher’s personality. These attitudes may have significant effects on how teachers teach, especially if they have an impact on teachers’ expectations. The way teachers approach integrating technology is very important. Marza stated three elements make up attitude: affective, behavioral, and cognitive.

Following the theory of social constructivism by Vygotsky (1978) one of the main goals of constructivist pedagogy and unique aspects of human experiences is learning how to use the systems and tools that mediate and transform human activity. Social constructivism emphasized that society promotes learning and teachers may support each other to enhance the new knowledge or tools in their school’s society (Bandura, 2001). In addition to teachers’ independent characteristics their beliefs, attitude, and efficacy in integrating technologies into their teaching process; teachers need to be well prepared and supported by their schools to use the tools and practice how to teach their content using technology (Baleghizadeh et al., 2016).

EFL Teacher’s Competencies with Elearning

Online learning or eLearning stands for any format of electronic education provided to students who do not need to be physically presented at an institution. This kind of learning allows the students to receive the materials online using electronic devices such as a computer, tablet, and even a smartphone (Liu et al., 2017). With eLearning educators and students can take courses from all around the world. They have more freedom and flexibility for online instructions related to time and place. eLearning is proven its effectiveness in educating people and raising their motivation. It allows participants to combine work, family, and studies. There are two main types of distance learning: synchronous and asynchronous. Synchronous communication happens in real-time. By contrast, asynchronous communication can happen over a long period. Synchronous learning is faster, more dynamic, great for active participation, and interactive discussion. With asynchronous teachers do not need to schedule. It tends to allow the teachers to record their lectures (Ogbonna et al., 2019).

A change in pedagogy is necessary for online learning and teaching. Online instruction calls for more drive and self-control than traditional classroom instruction. In comparison to teaching in conventional learning environments, it necessitates the development of teachers’ unique roles, skills, and competencies. A key idea in teacher preparation and development is competency-based education (CBE) and assessment.

Competency is what teachers bring to their teaching practices, including the appropriate knowledge, skills, attitudes, and beliefs (Farjon et al., 2019). Besides (CBE), the online educator needs to develop digital teaching competency (DTC). Digital teaching competency means a set of digital behaviors, practices, and identities (Falloon, 2020). A competency is used to identify what needs to be included in a typical training program (Burke, 2005). Proficient competency is viewed as a measurement level of associated language skills. Teachers’ competencies establish collaborative learning environments through their soft and hard skills. Guasch et al. (2018) stated that hard skills are specialized knowledge or training that a teacher has acquired through her career or other life experiences, such as her education. Soft skills are personal behaviors and characteristics that affect how teachers collaborate and work independently. Soft skills are crucial for a career in teaching and for fostering a productive workplace. To successfully complete technical tasks in a job, however, hard skills are required. According to Farmer and Ramsdale (2016), teachers’ digital competencies are categorized into general and specific competencies. The general digital competencies are identified into 12 components such as sharing effective learning practices with other teachers, providing support to learners, teaching students life skills, content facilitator, personal-professional competency, personal‑ethical competency, researcher, assessor, adviser, process facilitator, administrator, and designer (Setlhako, 2014). The particular competencies include creating digital learning materials, remixing learning materials, communicating, facilitating learning, utilizing appropriate pedagogical strategies, giving learners feedback, and evaluating learners’ performance using appropriate assessment strategies. Online learning can help students pursue highly individualized learning programs, provided by the digital teacher quality education and support. Teachers need to put in additional efforts to incorporate online learning programs into the curriculum in the most suitable manner (Ucar & Bozkaya, 2016). The context that the teachers teach and the actions they perform are intertwined.

Online Assessment Challenges

Schools turned from a teacher-centered approach into a student-centered learning approach. Drawing on the work of Piaget and Vygotsky, student-centered education practices are characterized as an instructional approach that engages students actively in their learning process. It is based on constructivist learning theory, which highlights the learner’s crucial role and emphasizes how they create meaning from new information and past experiences to include their interests and skills in the learning process (Sahin et al., 2016).

There are 4 key principles for a student-centered learning approach: personalized, competency-based, learning happens anywhere and anytime, where students take ownership (Goodman et al., 2018). Personalized learning acknowledges that students interact in various settings and with various activities. Individually paced, purposeful learning tasks that begin where the student is, assess pre-existing abilities and knowledge, and take into account the student’s needs and interests are beneficial to students. By encouraging one another’s growth and celebrating accomplishments, students take ownership of their learning and assessment through peer interaction. When students exhibit content mastery, they advance in their competency (Liang & Yang, 2017).

Student-centered classrooms include students in the planning, execution, and evaluation processes. The learners will become more active in their learning process if they are included in these decisions. The shift to a learner-centered teaching approach affected the assessment process. In student-centered the assessment process is designed to assess students’ passions, learning styles, and success skills. Students’ cognitive development should be directly examined as part of the assessment process by having them concentrate on learning and becoming familiar with the learning outcomes (Miranda et al., 2019). Acker and Hawksby (2019) argued that although instructors attempt to implement student-centered learning, they use teacher-centered pedagogical modes in the assessment. They focus on students passing the test more than developing their skills (Muganga & Ssenkusu, 2019). Few teachers differentiate between summative and formative assessment criteria. Thus, most teachers believe that assessment means testing and grading (Larasati, 2018).

Assessment is a critical aspect of the teaching and learning process. It aims to measure an individual’s ability, behaviors, or characteristics. Assessing subject learning outcomes is the focus of assessment (Ramsin & Mayall, 2019). One of the important considerations is the assessment purpose. Teachers need to know the purpose of their assessment process to provide an authentic assessment. According to Saefurrohman and Balinas (2016), there are three purposes of assessment: assessment for learning, assessment of learning, and assessment as learning. Rastgoo and Namvar (2010) defined assessment for learning as a set of strategies that are used to enhance learning and teaching. It creates feedback to improve students’ performance such as formative assessment. However, assessment as learning occurs when students are responsible to assess their learning process such as self-assessment. It develops and supports students’ metacognitive skills where students use teacher, peer, and self-assessment feedback to make modifications, improvements, and changes to what they understand to gain a sense of ownership and efficacy (Muller & Seufert, 2018).

The third purpose is the assessment of learning such as summative assessment which is designed for effective grading and ranking (Taras, 2005). It is highly affected by the validity and reliability of the activities. There are six types of assessment of learning: diagnostic assessments, formative assessments, summative assessments, Ipsative assessments, norm-referenced assessments, and criterion-referenced assessments (Muganga & Ssenkusu, 2019). Formative and summative assessments have received a great deal in education. Formative and summative assessments are two ways to evaluate a student’s learning process. Teachers use formative assessment to improve instructions and provide ongoing student feedback. They use it to decide whether to re-teach or move forward. It is used continuously throughout the lesson and integrated with the teachers’ instructions such as weekly quizzes or diagnostic tests before the teaching (Marion, 2018). Teachers can use a variety of formative assessment techniques and tools to assess their learners so they can receive intensive formative feedback that guides their learning. It carries out regular intervals. It helps students identify their strengths and weakness by using writing, quizzes, conversations, and other methods to evaluate themselves, their peers, and even their instructors (Black & William, 2018). Summative assessment is the summary of learning such as the unit test or the end-of-grade test. It is used to measure the students’ competency (Shute & Rahimi, 2017). Students need formative assessment feedback to give them a clear indication of their learning gap and where they need to be improved (Deluca et al., 2018). On the other hand, the summative assessment goal is to determine if the students meet the learning target. It is given after the instruction had occurred, and the results provide information about how students are doing for accountability and more formal progress (Broadbent et al., 2018). Summative assessments focus on the product rather than the process. It is a high-stakes assessment of learning to check if the learners are eligible to take further learning. Joseph (2007) stated that after a period of instruction, such as a unit, course, or program, summative assessment is used to assesses the learning, knowledge, proficiency, or success of the students. Yulia et al. (2019) claimed that there is a high requirement in education for utilizing online assessment tools to assess for formative and summative assessments.

Providing an alternative learning environment means different roles and different tools. The term ‘online’ usually means being connected to the Internet. In education, the term is associated with other terms such as “e-learning” and “blended learning”. Online assessment is known as an electronic assessment which means the use of information technology in various forms of assessment (Yulia et al., 2019). Cigdem et al. (2016) noted that the most critical condition in online teaching is an online assessment. If the assessment procedure is not authentic, reflects the educational goals, and indicates a clear report of the learner’s performance and educational level, the assessment can drive the learner in an antithetical direction. The way the students are assessed will be the greatest indicator of the effectiveness of the learning strategy (Cigdem et al., 2016). Cassady and Gridley (2005) hypothesized that online assessment has a huge impact on reducing students’ anxiety over the test compared with the usual summative assessment.

According to (Ziadat, 2021), in online learning teachers flipped the role with all types of students, including those with disabilities, and make them drive their learning. However, the parent’s role has a great influence to motivate and follow up on the student’s academic outcomes. Geva and Herbert (2012) insisted that learners with disabilities may face various challenges to acquire English as a second language thus teachers struggle with the traditional ways of teaching and assessing them and call for new accessible assessment tools for those students to foster their learning progress.

Research Question

The purpose of this study is to examine the impact of EFL teachers’ self-efficacy on their attitudes towards using online assessment tools by examining the factors of the technology acceptance model ease of usefulness and ease of use to assess English language learners with disabilities. It gives a clear focus on the teachers’ perceptions of using technology and online assessment as well. Remarkable literature agreed that the intrinsic factor, such as the perceived usefulness of technology, is crucial for the implementation of new technologies in educational settings. Attitudes and beliefs increase or decrease the adoption of technology by teachers.

The study emphasizes the need to determine how teachers’ practices are influenced by their beliefs about the value of using technology, including online assessment tools. This research aimed to recommend a standardized online assessment model to evaluate English language learners with disabilities instead of traditional ways of teaching and assessing especially during blended or virtual learning. It is anticipated that the findings of this research will help generalize the assumption of the positive impact of self-efficacy in TAM. The paper addresses the following research question:

What are the perceptions and attitudes of EFL teachers in Saudi Arabia using technology to assess English language learners to their usefulness and ease of use?

The Research Conceptual Framework

Figure 5.1. Research Framework

The conceptual framework for this study was mostly grounded in Bandura’s social cognitive constructivism theory and the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) to understand the relationship between English teachers’ attitudes towards online assessment tools with accepting and using technology. The social constructivist approach and individuals’ perceptions and understanding are intertwined (Arseven et al., 2016). Self-efficacy is a major component of social cognitive theory. Knowledge is actively constructed; learning is presented as a process of active discovery. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to explore EFL teachers’ perceptions, attitudes, and experiences toward assessing EFL learners through synchronic online teaching. The objective of this research is to suggest a coherent model to assess the English language’s main skills (reading, listening, writing, and speaking), and the sub-skills (grammar, spelling, and vocabulary) during online learning. To accomplish this objective, we examined the theory underlying Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) to provide the theoretical foundation for the survey questions and the interviews.

Theoretical background and empirical studies on teaching and electronic assessment of EFL skills are reviewed critically. This critical review helped the researcher to design the study most logically and appropriately. The focus of the study showed teachers’ acceptance of online teaching and assessing is guided and influenced by many factors. Some of these factors are the teachers’ attitudes and apprehensions regarding online assessments, online assessment accountability and accuracy, and perceptions of EFL teachers on the possible implementation of an online assessment. The preliminary results for this thematic research discussed the need for an authentic standardized online assessment model to support online teaching in EFL virtual learning environments in Saudi Arabia.

Methodology

Design/ Rationale of the Research

Figure 5.2. The relation between the variables

The study adopted mixed-method research. It refers to the systematic procedure for collecting, analyzing, and integration of both qualitative data (teachers’ open-ended interviews) and quantitative (survey) data to understand the research problem (Mckim, 2017). This study utilized a convergent design where qualitative and quantitative data were collected at the same time. The convergent method was used to gather and combine the collected data from different resources to reach the findings. In this research, the mixed-methods study consisted of a two-part methodology: the first part provided structured survey questions directed to the English teachers at Qatif girls’ schools in Eastern Province in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. In the second part of the study, twelve teachers from the 156 participants that returned fully completed the survey were purposively selected to take part in purposeful group interviews.

The dependent variable is the EFL teachers’ attitude towards accepting and using technology and the independent variable is the teachers’ self-efficacy. The research is grounded on the technology acceptance model (TAM) proposed by Davis (1989): perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use to analyze the relationship between these potential factors and how the impact the attitude and the intension to use. Both measures are important for comprehending how new technologies are received Because ease of use typically cannot make up for a system’s lack of perceived usefulness, perceived usefulness typically has a greater impact on usage than ease of use.

Regarding Bandura’s social influence, we expect that the EFL teachers’ positive attitude on accepting and using technology will have a positive effect on increasing their self-efficacy and that will be perceived useful by using effective online assessment tools to assess their learners. We used both the deductive process “the survey” and the inductive “interview” process to connect the theory with the empirical findings.

Setting/ Context of the Study

The data of this research is collected in the Eastern Providence region in Saudi Arabia. Eastern Providence is one of the advanced providences in the education sector. Education in Saudi Arabia has changed significantly. The Ministry of Education is intended to educate young students and prepare them for a future career (Barnawi & Al-Hawsawi, 2017). As a part of Saudi Vision 2030, equipping teachers and students with 21st-century skills is a demand to help them keep up with the lightning pace of today’s modern markets (Yusuf, 2017). The 21st-century skills are a set of abilities that teachers and students need to develop and succeed in their information age and working field (Larson & Miller, 2012). Saudi Government, education leaders, and policymakers support and strengthen the learners to grow and progress with these changes incorporating technology (Elyas & Al-Ghamdi, 2018).

EFL teachers in Eastern Province are all certified with a baccalaureate degree and some of them have higher education degrees such as master’s or Ph.D. Participants have different years of experience around 6-20 years in teaching English as a second language in Saudi Arabia. In the educational field, schools are currently using synchronic online teaching and conducting online tests and quizzes to evaluate the learners’ outcomes. There is limited research based on the use of online tools to deliver formative and summative online assessments for EFL/ESL skills. The perceptions of teaching effectiveness in an online environment are considered effective online assessment tools. Therefore, EFL teachers need to have a clear modality to be used in online assessment methods to evaluate the EFL students’ productive, receptive, and micro-linguistic skills.

Participants

The sample consisted of 156 anonymous English teachers, of whom 13 were males and 143 were females. 117 of whom were females in government schools, 37 of the sample were international schools, and 2 were in private schools. A questionnaire was conducted to find out to what extent teachers prefer online learning and use online assessment tools. In the second part of the study, twelve teachers from the 156 participants that returned and fully completed the survey were purposively selected to take part in the group interviews.

Ethics Statement

The teachers who participated in the survey had all taught English as a second language for at least six years. They received an invitation to participate in the survey, and no coercion or improper influence was used. Before completing the survey, they were informed in the written introduction of the anonymity and confidentiality of the collected responses and research findings. Standard socioeconomic studies claim that the participants’ anonymity is the only ethical issue at hand.

Data Collection Instrument

The survey instrument using Likert-scale was developed. The researcher referred to a group of English teachers in Qatif in the Eastern Province of Saudi Arabia to collect the data. A total number of 156 teachers participated in the survey and 12 teachers in the interviews. The research methods were used to obtain a rich and thorough description of the study that English teachers underwent. Under the guidance of the technology acceptance model (TAM), these tools were created. Thematic analysis was used to analyze the collected data.

The survey tool has been made available online for the collection of quantitative data. It has been predicted that using computer-assisted data collection will significantly increase the data’s reliability. The survey tool was distributed to a total of 350 English teachers. This sample consists of English teachers both male and female in government, private, and international schools. The online survey was conducted over three weeks, resulting in a sample size of 156 responses for an overall response rate of 44%. It is possible that users who were interested in using e-learning responded more frequently.

Procedure

The gathered data were examined using descriptive statistics. The Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) was used to analyze the survey responses. They were close-ended surveys and open-ended interview questions. The teachers’ survey was built on 15 close-ended questions concerning teachers’ perceptions and attitudes toward utilizing e-Learning tools to assess intermediate and secondary school ESL/EFL learners in Saudi Arabia in a technology-based environment. Five points Likert scale questions were included to examine teachers’ beliefs on the usefulness of using technology and teachers’ attitudes toward the ease of using online assessment tools.

To capture the qualitative data, purposeful group interviews were conducted with 12 English teachers who teach different levels. Approximately 25 minutes were spent with each participant through the zoom program. The interviews were recorded and coded into transcripts. Open-ended structured questions were asked to support the research assumption and figure out the relation between the variables.

Data Analysis

The questionnaire for the current study consisted of 15 items. The items were demographic questions that included the teachers’ gender, qualification, the type of school they teach in (government, private, or international), and the grades they teach. The independent variables measured the participants’ attitudes toward using and accepting technology. The responses to the questions were of the Likert type and ranged from one to five, where one meant the statement applied to the participant “Not at all” and five meant it did so “to a very high extent.” The results for the independent variables were exported to an SPSS file after the data had been cleaned and coded in Excel. The Statistical Package for Social Sciences (IBM SPSS) was used to run all statistical analyses. The data were organized and condensed using descriptive statistics. For the independent variables, the values of frequency, percent, and mean were computed. The summed attitude statements were used to calculate these statistics.

Results and Discussion

Interview Data

Online education is on the rise and more and more people are learning virtually. Teaching remotely is still relatively novel which depends on teachers’ attitudes and acceptance towards technology. English teachers positively agree that technology plays a major role in education. They used different types of technology implementations in their language classrooms including computers, visual projectors, electronic educational games, and different apps to facilitate the learning and teaching process. The purpose of this qualitative data is to prove the relation between EFL teachers’ self-efficacy in accepting and using technology. To accomplish the objectives of this research, descriptive thematical consistency analyses were done for the purposeful interviews. The number of participants was 12 EFL teachers (4 teach primary level, 4 teach intermediate level, 4 teach secondary level) who answered some structured questions about the teachers’ perceptions towards using online teaching and online assessment with EFL leaners both normal and those who have learning difficulties or disabilities. How much does teachers’ self-efficacy play a role in technological competency? Why do EFL teachers find it difficult to assess EFL learners’ skills productive, receptive, and micro-linguistic skills? How can online assessment give us a clear indication of the students’ levels?

Most teachers stated that integrating technology in education strengthens the learner’s engagement, facilitates the instructor’s role, and provides a structured, comprehensive learning experience for everyone involved. Regarding the increasing demand for using technology and e-learning, 7 teachers out of 9 who participated in the interview accepted the use of technology as a way of integration but not to be a complete teaching process. They claimed that blended learning, virtual classrooms, and learning management systems are all examples of this new era of teaching methodology, but they could not replace face-to-face teaching.

All the participants in the purposeful interview emphasized that, despite a lack of learner motivation, computer technologies could positively impact the quality of instruction, the mode of presentation, and authentic contexts. According to teachers’ responses, adoption, and use of technology in online learning are influenced by a variety of factors. They considered the teachers’ lack of computer expertise as a deciding factor. A teacher will experience stress and discomfort when teaching online if they are unable to effectively use computers in the classroom. Others cited by teachers included a lack of resources, abrupt technological issues, shoddy internet connections, computer phobia, issues with managing instruction, and outdated software and hardware.

All the teachers who participated in the purposeful interviews believed that using effective electronic games and apps is an effective way of teaching a foreign language as it encouraged students to be active in their learning. Taken together, they preferred computer-assisted language learning in EFL classes but not to be completely dependent on online virtual practices. All the participants agreed that teachers’ self-efficacy plays a pivotal role in technology acceptance. Teachers who are high performing have more self-efficacy rather than others. Those teachers find the technology useful and easy to use. It saves class time and minimizes the teachers’ efforts. Consequently, they develop a positive attitude toward this technology. They discussed some factors related to students’ socioeconomic aspect which make both the teachers and the students do not accept online teaching and learning.

They emphasized how the long-standing custom of students attending school or traveling to a physical institution to learn has been upended by the COVID-19 pandemic. The Internet has replaced printed books in today’s classrooms at colleges and universities, which use laptop and smartphone screens instead. Students from the poorest families, without Internet access and who could not afford electronic devices are more likely to be affected by this extraordinarily fast transition.

In addition, students with learning difficulties who do not receive family support may struggle with technology and online tools. If the students from these communities are unable to access online classes and receive the same amount and way of education as their peers, fewer of them will be able to proceed to higher education with good educational knowledge. The participants argued that the sudden shift to online education brought on by the COVID-19 pandemic runs the risk of escalating educational disparities in Saudi Arabia and around the world.

Furthermore, all the participants discussed that there were some barriers to teachers who use online teaching. They asserted that an eLearning environment has some barriers for both teachers and students. Through virtual learning, all students lack their interests and motivations. Few oral participations will be shared with the students. They lack cooperative learning norms and protocols. Other barriers related to teachers in using virtual learning in EFL including inadequate teacher training, lack of experimentation time and poor technical support. They declared that some EFL teachers turned back to lecturing in online teaching because they lack the techniques of blending eLearning with active learning strategies. They agreed that intensive training may improve the teachers’ skills in using technology and help them to accept virtual learning more. The teachers’ assumptions answered part of the research question which is how difficult is using the technology affected the EFL teachers’ attitude either positively or negatively in an online teaching environment. Teachers with high self-efficacy are more self-efficient about computers than others with low efficacy. Thus, they encourage the students to learn how to get the benefit of this technology to endorse their learning.

However, they reported that although schools focus on a student-centered approach in teaching practices, they still depend on the traditional way of assessing students through tests and quizzes especially low achievers and students with learning disabilities as a believe the traditional tools are easier and work better with those students. They commented that even if the use of technology provided the students with authentic language materials and resources which might develop their language skills, it cannot offer reliable online assessment tools to be a clear indicator to assess and evaluate the learners’ progress. The primary teachers’ participants found that the electronic apps and electronic games are suitable tools to conduct students’ formative assessments but not their summative assessments through an online platform based on the learners’ early ages.

On the other hand, the intermediate and secondary teachers believed that assessment is crucial to education where educators and parents use test results to assess the quality of the educational system and determine the students’ academic strengths and weaknesses.

The foundation of educational assessment is testing, which stands for a dedication to high academic standards and school accountability. Students must first understand where they are to know where they are going. When the tests are too narrow or are not properly aligned to standards, they provide little concrete information that teachers and schools can use to improve teaching and learning practices and measure the learners’ outcomes. Teachers start teaching to the test simply to raise scores, frequently at the expense of more meaningful learning activities. Since the introduction of online learning in Saudi Arabia, educators, administrators, and school districts have struggled with the issue of how to evaluate distance learners accurately and fairly. The majority declared that assessment strategies should be changed and shifted from quizzes and tests to new modeling to match the new strategies of online teaching. Seven teachers from the participants raised a standing point regarding some cultural factors. They pointed out the need to adapt to the new eLearning environment by asking the students to open their cameras during the mid-term or final examinations to assure the test process reliability and validity. The interview results were used to support the survey analysis.

Survey Data

The findings from the survey that were used to address the research questions are presented in the section that follows. The survey was built into three themes. The first theme was the EFL teachers’ perceptions about the ease of using online teaching and implementing the online assessment. The second theme was teachers’ beliefs about the usefulness of online assessment and how much it indicated accuracy in the assessment and evaluation process. The third theme was about the EFL teacher’s attitude and apprehensions regarding online teaching and assessments. Five questions were designed under each theme by using a Likert scale to analyze the relation between the EFL teachers’ attitude and technology acceptance components ease of use and usefulness. The sample consisted of 156 male and female teachers, of whom 13 were male and 143 female teachers. All the participants were English language teachers. 117 teachers teach in government schools, 37 of the sample taught in an international school, and 2 were private schools teachers. The survey was conducted to find out to what extent teachers use technology and prefer online learning (see table 5.1).

Table 5.1. Demographic information of the participants

|

Statistics |

|||||

|

Gender |

What is the type of school you teach at? |

What groups of students you are teaching? |

What is your highest qualification? |

||

|

N |

Valid |

156 |

156 |

156 |

156 |

|

Missing |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

|

Mean |

1.9167 |

1.4872 |

2.0833 |

1.9359 |

|

|

Std. Deviation |

0.27728 |

0.85374 |

0.90131 |

0.31479 |

|

Research Results

Based on the statistics and analysis of the gathered survey, this section examined the relationship between all TAM variables. To determine which independent variables, have a relationship with the dependent variable, regression analysis was used. In this study, we look at how attitude toward use and intention to use relate to perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use. We also looked at how these relationships take shape. There were three relationships we examined to explore the coefficients and differences among these variables. They were:

The relationship between perceived ease of use and perceived usefulness.

The relationship among perceived ease of use, perceived usefulness, and attitude to use.

The relationship among perceived usefulness, attitude to use, and intention to use.

Table 5.2. Theme One: Perceived Ease of Use

|

Variables |

participants |

Not at all |

|

To a very little extent |

|

To little extent |

|

To high extent |

|

To a very high extent |

|

Mean |

St. deviation |

|

freq |

% |

freq |

% |

freq |

% |

freq |

% |

freq |

% |

||||

|

To what extent is it easy to teach through a virtual online environment |

156 |

8 |

5.1 |

27 |

17.3 |

78 |

50.0 |

43 |

27.6 |

0 |

0 |

3.0000 |

.81121 |

|

To what extent does using online assessment materials help in catching individual students’ needs |

156 |

12 |

7.7 |

62 |

39.7 |

54 |

34.6 |

16 |

10.3 |

12 |

7.7 |

3.2949 |

1.01738 |

|

To what extent online tools could be used to conduct a summative evaluation |

156 |

59 |

37.8 |

22 |

14.1 |

46 |

29.5 |

10 |

6.4 |

19 |

12.2 |

3.3526 |

1.07045 |

|

To what extent it is easy for EFL teachers to become skillful at using online assessment tools |

156 |

10 |

6.4 |

24 |

15.4 |

48 |

30.8 |

52 |

33.3 |

22 |

14.1 |

3.3333 |

1.09741 |

|

To what extent can online assessment be used to facilitate quick and clear reports on candidate results and progress |

156 |

5 |

3.2 |

15 |

9.6 |

34 |

21.8 |

64 |

41.0 |

38 |

24.4 |

3.7372 |

1.03557 |

The result of the second theme questions showed that 78 teachers to a little extent believed in the easiness of teaching through the virtual online environment and none of them to a very high extent believed in the ease of using technology in teaching virtually. To a very little extent, teachers found that using online assessment materials can help in catching individual students’ needs, and to a little extent, it is easy for EFL teachers to become skillful at using online assessment tools. However, the majority believed there are not sufficient online assessment tools to evaluate the learners’ learning outcomes.

Table 5.3. Theme Two: Perceived Usefulness

|

Variables |

participants |

Not at all |

|

To a very little extent |

|

To little extent |

|

To high extent |

|

To a very high extent |

|

Mean |

St. deviation |

|

freq |

% |

freq |

% |

freq |

% |

freq |

% |

freq |

% |

||||

|

To what extent can online assessment experiences improve students with learning disabilities and English language skills |

156 |

10 |

6.4 |

24 |

15.4 |

48 |

30.8 |

42 |

26.9 |

32 |

20.5 |

3.3974 |

1.16220 |

|

To what extent can online assessment be considered to be a useful and accurate indicator for all EFL learners to promote them to a further language level? |

156 |

5 |

3.2 |

67 |

42.9 |

34 |

21.8 |

35 |

22.4 |

15 |

9.6 |

3.7179 |

1.02104 |

|

To what extend do you think there are sufficient online assessment tools to assess receptive skills (reading/listening) |

156 |

9 |

5.8 |

25 |

16.0 |

46 |

29.5 |

55 |

35.3 |

21 |

13.5 |

3.3462 |

1.08154 |

|

To what extend do you think there are sufficient online assessment tools to assess productive skills (speaking/writing) |

156 |

11 |

54 |

34.6 |

19.2 |

47 |

30.1 |

7.1 |

30 |

14 |

9.0 |

3.1923 |

1.07232 |

|

To what extend do you think there are sufficient online assessment tools to assess micro-linguistic aspects (vocabulary/grammar) |

156 |

7 |

4.5 |

53 |

34.0 |

56 |

35.9 |

18 |

11.5 |

22 |

14.1 |

3.4167 |

1.01574 |

The second theme measured teachers’ perceived usefulness and how it is correlated with teachers’ attitudes and intentions to use. The statistics showed that 48 teachers to a little extent find online assessment experiences can improve student’s English language skills. To the very little extent which is 67 teachers can consider online assessment as a useful and accurate indicator for EFL learners to promote them to a further language level. However, the majority of the teachers to very little extent believed that there are sufficient online assessment tools to assess both receptive and productive skills as well as the micro-linguistic aspects (vocabulary/grammar).

Table 5.4. Theme Three: Teacher’s attitude

|

Variables |

participants |

Not at all |

|

To a very little extent |

|

To little extent |

|

To high extent |

|

To a very high extent |

|

Mean |

St. deviation |

|

freq |

% |

freq |

% |

freq |

% |

freq |

% |

freq |

% |

||||

|

To what extent do EFL teachers prefer online learning and teaching |

156 |

11 |

7.1 |

19 |

12.2 |

67 |

42.9 |

47 |

30.1 |

12 |

7.7 |

3.1923 |

0.99103 |

|

To what extent can online assessment results modify teaching practices |

156 |

12 |

7.7 |

27 |

17.3 |

70 |

44.9 |

39 |

25.0 |

8 |

5.1 |

3.0256 |

0.97019 |

|

To what extent do teachers believe that the lack of online facilities and resources is a big challenge to applying online assessment |

156 |

54 |

34.6 |

19 |

12.2 |

18 |

11.5 |

28 |

17.9 |

37 |

23.7 |

2.8397 |

1.62042 |

|

To what extent do you believe that teachers’ efficacy plays a role in technological competency and acceptance |

156 |

6 |

3.8 |

9 |

5.8 |

34 |

21.8 |

63 |

40.4 |

44 |

28.2 |

3.8333 |

1.02758 |

|

To what extent do you believe that standardized online assessment makes students result more diverse |

156 |

9 |

5.8 |

20 |

12.8 |

56 |

35.9 |

61 |

39.1 |

10 |

6.4 |

3.2756 |

0.96770 |

The third theme questions trends showed that 47 teachers to a high extent prefer online learning and teaching while 63 teachers to a high extent believed in the effect of the teachers’ efficacy role in technological competency and acceptance. On the other hand, just 8 teachers to a very high extent believed the ability of online assessment results in modifying teaching practices, and 56 teachers to a little extent believed that the standardized online assessment can make the students’ results more diverse.

Discussion and Conclusion

The TAM placed a strong emphasis on the importance of teachers’ attitudes and beliefs regarding the use of online teaching in educational settings and can therefore be seen as having an impact on how they use online assessment. Despite Bandura’s theory and the TAM model being used to address the research question and support the adoption of online teaching and assessment in the educational sector, these attitudes and beliefs are crucial.

As a result, we looked over the literature on teachers’ attitudes and beliefs. We have focused on the terminology used in the TAM because this is the dominant model in this study trying to find the relation between ease of use, usefulness, and attitude. According to the teachers’ responses to the first and second theme, they agreed that self-efficacy is a factor that influenced the teacher’s attitude and apprehensions regarding online teaching and assessments, the result showed that teachers appeared to accept that the use of ICT would make their teaching practices easier by assisting them with different sources of knowledge that allow students to combine information more effectively. Their answers reflected their beliefs, attitudes, and values that allow the adoption of technology by teachers. In contrast, they did not agree with the usefulness of using technology in the assessment process. Although they agree with the variety and sufficient online assessment tools, they did not see the online assessment tools as a clear indicator of the learners’ progress.

As seen in the above-mentioned literature review, the new assessment practices may have imposed new demands on teachers’ knowledge, abilities, and challenged. The limitation of answering the questions related to the usefulness of the online assessment methods is the fact that teachers’ conceptions of the method, function, and process of online assessment influence all their pedagogical actions. The new assessment practices may have imposed new demands on teachers’ knowledge, abilities, and challenged. Answering questions about the usefulness of online assessment methods is limited by the fact that teachers’ conceptions of the method’s function and process influence all their pedagogical actions.

The findings of the study showed the impact of teachers’ self-efficacy on teachers’ attitudes toward using technology which influenced their beliefs on the usefulness of using online assessment tools. EFL teachers need to track the student’s understanding and areas of weakness during the online learning process which allows the teachers to adjust their teaching practices according to the formative assessment outcome. On the other hand, they need to conduct a test at the end of the learning process (summative assessments) to evaluate the students’ outcomes. New online teaching practices need new assessment and new evaluation methodologies to adapt to the changes either in teaching practices or assessment methods. Focusing on usual tests and quizzes as a parameter to evaluate the students’ main skills in the English language would not give a clear test validity result.

The study analyzed 156 teachers’ perceptions of using technology in online teaching and online assessment practices and their relationship to teacher efficacy. The qualitative and quantitative findings indicated that teachers had a variety of related conceptions, and it was necessary to develop complex models to comprehend how teachers were approaching the nature and goals of online assessment in the context of a virtual learning environment.

We acknowledged that the teachers were not familiar with the appropriate online assessment models as the majority responded there are not sufficient online learning tools to assess and evaluate the learners’ outcomes. They believed in one way of assessment which is quizzes and tests. Since we teach by using the learner-centered approach, we need to create authentic assessment activities in the online environment. Online assessment can promote active learning and build a sense of community among students and their teachers if it is designed appropriately. Online assessments are an essential component of eLearning and should be taken into account.

Limitations

The study has some limitations that could be investigated in future research studies. The difficulty of examining teachers’ attitudes toward the value of using technology in the assessment process is a glaring limitation of this study. The inconsistency between the way we teach and the way we assess the learners. We teach a student-centered approach, but we assess them in a very traditional way through individual exams and individually assigned tasks. This limitation of the study merged from the flawed teachers’ experiences on different learning management systems (LMSs) that offered a variety of capabilities for implementing different online assessment techniques. Another limitation regarding the reliability of teachers’ responses. Teachers may not have wanted to voice their disapproval of the institution’s assessment practices maintaining their professional standing. More research is required to establish a link between teachers’ beliefs about online assessment and how those beliefs influence their practices. To correlate factors like age, years of experience, and educational background with beliefs, more research is required. Due to time restrictions, these factors were not considered in the current study.

Conclusion and Recommendation

Understanding the factors that affect how teachers perceive online teaching and online assessment usefulness is a significant value for educators, teachers, curricula designers, and eLearning management when they are attempting to design e-course activities and tasks to be more useful and helpful for teachers to use different online assessment tools to evaluate their students. Based on the survey, the impacts of EFL teachers’ self-efficacy factor on perceived usefulness were investigated. To successfully employ online teaching, it is important to know how well eLearning supports the assessment process.

Our research shows a positive influence of self-efficacy on eLearning perceived usefulness. That confirmed the importance of developing teachers’ self-efficacy to improve virtual teaching practices. It is important to have a clear standardized online assessment modality to help the teachers give clear, reliable feedback and evaluation record about the learning process and the students’ outcomes. Teachers and students will feel more at ease and be more motivated to study if the e-course materials and activities are well-prepared and simple to use. The effective communication between students and teachers is essential to the success of eLearning, and this can be maintained by encouraging students’ self-efficacy regarding the simplicity and value of eLearning.

This fact suggests that teachers should have faith in their ability to teach in and assess students in an online learning environment. Furthermore, to contribute comprehensive experiences to the field of educational research, teachers should be proficient in both technological know-how and online pedagogy. To enable the teachers’ professional development, there should be standardized guidelines for online teaching, learning, and assessment procedures using ICT for English as a second language in Saudi schools.

Consequently, that may help them to become competent, independent, and confident in using the various eLearning system functionalities. Tests and quizzes are not the only formative and summative assessment methods of assessment so they would not be appropriate to be used in an eLearning environment. Students need to be prepared for a higher level of thinking rather than comprehending and remembering. These could be reached by involving them in different authentic tasks to assess and evaluate their educational progress. Here we are listing some examples of sufficient authentic tasks which could be used in online English language classes to sustain reliable and valid assessment results for EFL learners and students with learning disabilities:

- Using Polls or online surveys are crucial because the learners complete them quickly and they allow the learners to express their opinions. However, they help EFL teachers to capture feedback directly from their students about their learning experience and that helps them to assess how the students are getting improve in reading comprehension and speaking skills.

- Game-based assessments improve the growth of non-cognitive skills like discipline, risk-taking, collaboration, and problem-solving.

- Peer evaluation flips the roles and puts the students in the position of the instructor, allowing them to review and edit each other’s performance and tasks. Such exercises give each participant the chance to consider their understanding and then express it in a consistent and organized manner, which aids the students in developing their reading and writing skills.

- A forum is an online discussion board that is focused on a particular subject. The platform approved by the school is asking students to contribute to a forum post. It is a great way to determine their level of comprehension, pique their interest, and facilitate their learning. Teachers can continuously assess their students’ speaking and listening abilities through this activity. Students are asked to think critically about a question that is presented to them or that they are listening to that is based on a reading or a lesson. Their responses are published on a forum where their classmates can comment. This technique can be used by teachers to assess their students’ understanding of a subject while encouraging interaction, communication, and collaboration among them.

- A dialog simulation can help students prepare for conversations with clients, coworkers, and other people in the real world. Give students advance notice of what to expect and give them a secure environment in which to practice their reactions and responses when developing conversation activities based on scenarios they might encounter at work. These activities can be used as a tool to assess the use of the language micro-linguistic aspects such as spelling, grammar, and vocabulary. Thus, it developed their ITC skills in using PowerPoint, or scenario-based learning apps such as Plotagon. Incorporating a video conference or online simulation tasks can demonstrate the students’ proficiency in language, mathematics, computer, engineering, and other courses and this is the core of 21st-century skills that Saudi Vision 2030 aimed to sustain in the educational field. Preparing the school students for their future careers by equipping them with advanced technological skills.

- Project-based learning connected with quizzes based on each student’s experience in his/her project is an excellent way to engage student learning. As a result, students will acquire in-depth subject knowledge as well as technology-integrated critical thinking, collaboration, creativity, and communication skills.

Significance of the Study

This research paper highly recommends a clear purposeful online assessment method for English as a second language to shift the EFL teachers’ perceptions towards the insufficiency of using technology to assess EFL learners with difficulties. Thinking about the grading system is one of the teachers’ challenges in eLearning. On the other hand, EFL teachers’ positive attitudes and high self-efficacy encourage the policymakers and the educational designers to provide consistent assessment methods that integrated with the eLearning experience.

By making teachers more aware of the benefits of using online teaching and the online assessment process, we think our study makes a valuable contribution to the pertinent literature. It provides a detailed insight into factors that positively influence eLearning among EFL Saudi teachers and teachers elsewhere.

References

Abdullah, F., Ward, R., & Ahmed, E. (2016). Investigating the influence of the most commonly used external variables of TAM on students’ Perceived Ease of Use (PEOU) and Perceived Usefulness (PU) of e-portfolios. Computers in Human Behavior, 63, 75-90. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2016.05.014

Acker, A., & Hawksby, E. (2019). Competence committee: How meeting frequency impacts committee function and learner-centered assessment. Medical Teacher, 42(4), 472-473. doi:10.1080/0142159x.2019.1627302

Aizawa, I., Rose, H., Thompson, G., & Curle, S. (2020). Beyond the threshold: Exploring English language proficiency, linguistic challenges, and academic language skills of Japanese students in an English medium instruction programme. Language Teaching Research, 1-25. doi:10.1177/1362168820965510

Albirini, A. (2006). Teachers’ attitudes toward information and communication technologies: The case of Syrian EFL teachers. Computers & Education, 47(4), 373-398. doi:10.1016/j.compedu.2004.10.013

Al-Fraihat, D., Joy, M., Masa’deh, R., & Sinclair, J. (2020). Evaluating E-learning systems success: An empirical study. Computers in Human Behavior, 102, 67-86. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2019.08.004

Ali, H., & Ajmi, A. (2013). Towards quality assessment in an EFL programme. English Language Teaching, 6(10), 132-148. doi:10.5539/elt.v6n10p132

Ashraf, H., Motallebzadeh, K., & Ghazizadeh, F. (2016). The Impact of Electronic–Based dynamic assessment on the listening skill of Iranian EFL learners. International Journal of Language Testing, 6(1), 24-32. Retrieved from ResearchGate.

Ayoobiyan, H., & Soleimani, T. (2015). The relationship between self-efficacy and language proficiency: A case of Iranian medical students. Journal of Applied Linguistics and Language Research, 2(4), 158-167. Retrieved from https://www.jallr.com

Baleghizadeh, S., Goldouz, E., & Boylan, M. (2016). The relationship between Iranian EFL teachers’ collective efficacy beliefs, teaching experience and perception of teacher empowerment. Cogent Education, 3(1), 1223262. doi:10.1080/2331186x.2016.1223262

Bañados, E. (2013). A Blended-learning pedagogical model for teaching and learning EFL successfully through an online interactive multimedia environment. CALICO Journal, 23(3), 533-550. doi:10.1558/cj.v23i3.533-550

Bandura, A. (2001). Social cognitive theory of mass communication. Media Psychology, 3(3), 265-299. doi:10.1207/s1532785xmep0303_03

Barnawi, O., & Al-Hawsawi, S. (2017). English education policy in Saudi Arabia: English language education policy in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia: Current trends, issues, and challenges. Language Policy English Language Education Policy in the Middle East and North Africa, 13, 199-222. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-46778-8_12

Barrouillet, P. (2015). Theories of cognitive development: From piaget to today. Developmental Review, 38, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dr.2015.07.004

Behroozizad, S., Nambiar, R., & Amir, Z. (2014). Sociocultural theory as an approach to aid EFL learners. The Reading Matrix, 14(2), 217-226. Retrieved from http://www.readingmatrix.com/files/11-09507mh3.pdf

Bhagat, K., & Spector, M. (2017). Formative assessment in complex problem-solving domains: The emerging role of assessment technologies. International Forum of Educational Technology & Society, 20(4), 312-317. Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.2307/26229226

Black, P., & Wiliam, D. (2018). Classroom assessment and pedagogy. Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy & Practice, 25(6), 551-575. doi:10.1080/0969594x.2018.1441807

Brader, A., Luke, A., Klenowski, V., Connolly, S., & Behzadpour, A. (2013). Designing online assessment tools for disengaged youth. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 18(7), 698-717. doi:10.1080/13603116.2013.817617

Broadbent, J., Panadero, E., & Boud, D. (2018). Implementing summative assessment with a formative flavour: A case study in a large class. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 43(2), 307-322. doi:10.1080/02602938.2017.1343455

Burke, J. (2005). Competency based education and training. Retrieved from https://books.google.com.sa/books

Burney, V. (2008). Applications of Social Cognitive Theory to Gifted Education. Roeper Review, 30(2), 130-139. doi:10.1080/02783190801955335

Cakır, R., & Solak, E. (2015). Attitude of Turkish EFL learners towards e-Learning through Tam Model. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 176, 596-601. doi:10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.01.515

Carey, S., Zaitchik, D., & Bascandziev, I. (2015). Theories of development: In dialog with Jean Piaget. Developmental Review, 38, 36–54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dr.2015.07.003

Cassady, J., & Gridley, B. (2005). The effects of online formative and summative assessment on test anxiety and performance. The Journal of Technology, Learning, and Assessment, 4(1), 1-31. Retrieved from ttps://www.jtla.org

Cheng, B., Wang, M., Moormann, J., Olaniran, B., & Chen, N. (2012). The effects of organizational learning environment factors on e-learning acceptance. Computers & Education, 58(3), 885-899. doi:10.1016/j.compedu.2011.10.014