Chapter And Authors Information

Content

Abstract

The feminist movement has had a profound impact on all aspects of life, especially in the study of literature and language, leading to the birth of Feminist Stylistics. Feminist Stylistics has changed human perception related to the women writers’ issues in the areas of love, family, and sexuality through gender-relevant language. For modern Vietnamese literature, the expression of feminism in works is gaining increasing attention from researchers, particularly in prose works. Feminism is expressed in how contemporary female authors assert female voices in their creations. This chapter employs the feminist stylistics framework of Sara Mills in assessing female characters as well as the identification of authors’ distinct writing styles in the modern prose works of Vietnamese women. Based on the analysis of selected prose works at two text creation and text reception, this chapter clarifies female value in contemporary Vietnamese literature, thereby contributing to changing perceptions of knowledge and the realities of society about gender equality in literature. Finally, the study reveals that sexism and gender stereotyping are found in the prose works, characteristic of the writing of a female author expressing herself as a woman living in a male-dominated society.

Keywords

Feminist, Prose Works, Male-Dominated Society, Vietnamese Women Writers, Sara Mills

Introduction

Feminist Stylistics has been attracting the attention of both linguists and readers, examining linguistic features of works in relation to styles and gendered language. Feminist Stylistics is reviewed and studied, not only to establish a clear understanding of how gender issues are represented in texts, but also to identify issues related to women reflected in perceptions of the authors in aspects of love, marriage, family, and sexuality. These perceptions help define the image and position of women in real life; at the same time, literature also creates distinct and unique features in the language. The study of the feminist stylistics of a specific author contributes to linguistics in relation to feminist stylistics. This study can lead to a change in people’s perceptions of issues related to women in literature in particular and in society in general.

Sexism is a major concern of Feminist Stylistics, which examines issues of sexism in literary works. To analyze gender discrimination, feminist stylists around the world have developed many research directions, such as the question “who did what to whom?,” which allows researchers to examine transliteration patterns in texts and the process of implied discrimination.

In Vietnam, gender preference and discrimination are clearly manifested in daily life. Under the feudal system, this ideology was very popular. Men were always valued and given priority over women. Although women’s rights are now recognized and gender equality in Vietnam has made certain achievements, the idea of “respecting men and disrespecting women” has not completely disappeared. In fact, this ideology still exists in many different regions and is expressed at different levels. Many families still adhere to the ideology of preferring sons to carry on the family lineage, as sons are traditionally seen as the heirs to property and assets. Consequently, they often resort to extreme measures to ensure the birth of a son, leading to a skewed gender balance in Vietnam. In 2021, Vietnam’s sex ratio at birth stood at 111.5 boys for every 100 girls. These deviations from the natural biological balance indicate deliberate interventions that jeopardize the country’s population stability.

Furthermore, many families exhibit gender discrimination, favoring sons over daughters and treating them unequally. Sons typically enjoy more rights and protection, while daughters are often assigned domestic chores such as cooking and cleaning. These ingrained biases inadvertently perpetuate inequality, burdening women with unspecified familial responsibilities. As a result, women become confined within the domestic sphere, heavily reliant on men for support.

According to an analysis report based on data from the International Labor Organization’s Labor and Employment Survey, women spend, on average, twice as many hours as men on household chores. Shockingly, approximately 20% of Vietnamese men do not contribute to household tasks at all, leaving the bulk of the burden on women’s shoulders.

The ideology of “respecting men and despising women” also contributes to the perpetuation of male patriarchy. The prevalence of violence, trafficking, and abuse against women and girls, alongside the adverse effects of marriages involving foreign elements, have shown no signs of improvement in recent times. According to the 2019 National Survey on Violence against Women in Vietnam3, nearly two out of every three women (almost 63%) have experienced one or more forms of physical, sexual, emotional, or economic violence. Moreover, instances of violence against women often remain undisclosed, with approximately 50% of abused women never confiding in anyone about their experiences. Shockingly, the majority of women (90.4%) who endure physical or sexual violence from their spouses do not seek assistance from government agencies or unions.

Although there is no official confirmation of whether or not feminism is presented in Vietnamese literary works, we find that many Vietnamese female authors clearly express female divinity and feminism in their works. The most significant are female authors of short stories. Despite different compositional styles, each work vividly reflects both daily life and the multidimensional inner world of characters’ passions. In the world of short stories, Y Ban and Nguyen Ngoc Tu are two typical representatives of female authors in two adjacent periods of contemporary Vietnamese short stories. Growing up in the early 1990s, Y Ban published at the time when Vietnamese literature was experiencing a growth of published female writers (e.g., Duong Thu Huong, Pham Thi Hoai, Phan Thi Vang Anh, Pham Thi Minh, Thu, Nguyen Thi Hue, Vo Thi Hao, Vo Thi Xuan Ha). Commenting on her own work, Y Ban once admitted that part of her literary success can be attributed to her subject: writing about women. Y Ban’s short stories reflect a concern for women’s lives. Using words, sentences, and expressions from daily life, Y Ban’s characters honestly express legitimate feelings, thoughts, moods, and aspirations about feminism in their lives. Although her characters are sometimes short-lived, they leave a lasting impression in readers’ mind. These characters are often depicted as ready to sacrifice for their lovers. They courageously admit mistakes when they make mistakes, persevere when they fail, and express a desire to be trusted and loved, which motivates their actions. And different from characters who follow traditional roles of previous generations, they do not hesitate to overcome barriers, engage with love, and leave behind their feudal customs. In their lives, they openly express their sexual desires and the desire to live and be loved.

Appearing a decade after Y Ban, Nguyen Ngoc Tu, with her diverse and unique use of language, highlights many issues about women in her work. Choosing a simple, honest, liberal, and open expression, Nguyen Ngoc Tu always has a direct approach to delicate and is difficult-to-express issues that the previous generation chose to hide or ignore. In most of her works, Nguyen Ngoc Tu portrays the instincts of her female characters with a lot of honesty. Her characters live in a world where feminism is always neglected. However, they have always courageously and frankly faced the thorny problems of life with the hope that one day the lives of women like them will be better. Therefore, with the analysis of these writers’ language based on the theoretical framework of feminist stylistics, we want to clarify the characteristics of these two writers’ work, thereby comparing their perspectives and views on the issue of feminism in different periods. As a result, readers will be given a better understanding of feminism in Vietnamese literature; at the same time, this study can help readers to make connections to gender equality in real-life Vietnamese society.

In this chapter, we survey a number of contemporary Vietnamese female prose works to review and analyze the transference model and, thereby, examine the forms and styles used in depicting gender discrimination or preference in the texts. In this way, we can see how deeply gender discrimination is ingrained in the subconscious and how it affects the lives of Vietnamese people in general and women in particular. At the same time, when analyzing the transfer pattern in the text, we also consider how women express their resistance to gender discrimination reflected by the writers. From there, we hope to bring a specific and highly applicable perspective to Feminist Stylistics research in literature and life. We aim to clarify the characteristics of the word “art” in the context of Vietnamese women’s writing, thereby showing the differences in the perspectives and views of the two authors on feminism in different literary periods. To achieve the research purpose, the authors conducted a survey and analysis of feminist characteristics based on the linguistic aspects of the works in relation to style. This research sheds light on feminism in literature and the female ego as expressed in poetry, while promoting women’s rights and fostering gender equality in Vietnamese society.

An Overview of Feminist Stylistics and Transitivity Models

Feminist Stylistics Concepts

Beginning in western Europe and the United States in the mid-nineteenth century, Feminist Stylistics traces its origins to the early feminist movement. As a doctrine of equal social, economic, and political rights, feminism holds that there must be equality in the granting of rights and opportunities to men and women. Originating from this concept, activities to fight for the rights and position of women in society were in turn born with the name feminism.

Over hundreds of years, with the common goal of equal rights for women and condemn all forms of discrimination against women and children, the feminist movement has continued to develop. In fact, the above-mentioned feminist movements have greatly influenced social life in many ways, from the economic to the political, cultural, and social. With the function of reflecting real life, literary and linguistic studies were also affected by feminism, and from this, the Feminist Stylistics subdiscipline was formed.

According to the Spanish researcher Rocio Montoro (2014), “Feminist stylistics is a form of stylistics that seeks to understand how gender issues are expressed in the text through the examination of linguistic aspects of the work in relation to style” (Montoro, 2014, p. 346). According to Montoro (2014), the first person to use the term “feminist stylistics” instead of the term “Marxist feminist stylistics” is an important theorist of the stylistic subdivision: Sara Mills. Although not a pioneer in the study of feminist stylistics, Mills was the first to coin the term. She conducted extensive research on issues related to feminist styles. To further clarify the concept of feminist styles, Mills (1995, 2005) considers this approach to be a specific form of analysis and states: “Both the terms ‘feminism’ and ‘style’ are complex terms, and for the reader they are interpreted in many different senses. However, the term feminist stylistics is the best term that can best summarize my interest in a form of analysis that is itself feminist, and linguistic analysis is the central way used to examine texts” (p. 1). Therefore, Mills (1995, 2005) argues that, when analyzing a text from a Chinese perspective, the researcher does not only understand and analyze how sexism is described in the text at the word level but also at the discourse level. The researcher explains, “At this level, aspects such as point of view, force, metaphor or unexpected transformation are closely related to gender issues that need to be analyzed specifically in order to help the researcher investigate whether ‘feminine writing’ is explicitly described in the text” (Mills, 1995, 2005, p. 1).

In addition to providing a definition of Feminist Stylistics, both Mills (1995, 2005) and Montoro (2014) discuss the starting point of Feminist Stylistics. Both researchers agree that Feminist Stylistics acknowledges male dominance as real and that this manifests in the way they portray women in society. Such issues are studied by Feminist Stylistics researchers at the textual level on the basis of linguistics related to gender. Montoro (2014) further notes that Feminist Stylistics place less emphasis on the artistic function of language. For them, the beauty of the form and language in the text is not an important factor to analyze, but rather the techniques used in the text, such as the way sexism is expressed in the text, is the center of analysis. Recognizing that literature not only reflects but also creates culture, Feminist Stylistics researchers argue that the study of literature either perpetuates oppression against women or helps to eliminate it. To further explain this point of view, Mills observes that, in a systematic way, Feminist Stylistics highlight the self-conscious attempts of female writers to change the traditional paradigm of language usage. To do that, they identify details that are masculine jargon as well as the expressions that replace them in the text.

In short, fueled by political motivations aimed at developing awareness, the advent of Feminist Stylistics marked a development in the scientific study of specific perceptions and actions of women against gender discrimination reflected in many fields including literature. The emergence and development of feminist style has created conditions for authors to reflect more clearly and fully on issues related to women, especially in the areas of love, family, and sexuality. This has led to a change in awareness about women’s positions in literature and in society in general, namely, the highlighting of gender barriers that still exist today.

Analysis of Point of View and Transitivity Model

So far, to analyze gender discrimination, Feminist Stylistics researchers have deployed many research directions. At an early stage, when discrimination was a primary concern, the research direction of Feminist Stylistics focused mainly on the study of words used to show gender bias or the way in which words and structures are used to describe female or male characters and their relationship in a text to reveal a message about gender discrimination. Later, Feminist Stylistics researchers extended their analyses to the level of discourse; for example, analyzing a character’s direct or indirect narrative to find gender bias or preference expressed in the way a character is expected or valued or has more authority over other characters. Feminist stylistics, as a field, moved from analyzing the vocabulary describing characters to analyzing the point of view from which the character is observed and depicted. Based on points of view, Feminist Stylistics researchers focus on analyzing indirect forms of gender discrimination, such as sarcasm, irony, and humor.

Feminist Stylistics also focuses on analyzing transitivity. According to Montoro (2014), Burton uses the transference model as a research framework because this researcher believes that “the transference model focuses on looking at how experiences or experience is coded in language” (Burton, 1982, cited in Montoro, 2014, p. 353). By examining the process of “who does what to whom?,” Burton concludes that the transference model can help analysis. Also, according to Montoro (2014), Ryder agrees with Burton because Ryder thinks that analysis follows the transfer model, that is, considers the process and the people involved in the process. Participants and the events depicted in texts can help illustrate how individual experiences or socially significant events are encoded by the language. Montoro (2014) also cites an example when referring to the case of Mills, who applied the model of transitivity of Burton outlined above in the manner of “who did what to whom?” to the analysis of some pop songs. Mills proposed that finding the meaning of songs through the analysis of the transferred pattern should be properly understood in the social context, not simply in the relationship between form and language functions. Therefore, Montoro (2014, p. 356) argues that Feminist Stylistics are always interested in understanding gender issues as well as the transitivity models used in the text to clarify the way in which language has represented gender-related issues.

Vietnam’s Social Context in Relation to Feminism

In the primitive or matrilineal communal period (about thirty to forty thousand years ago), women were valued more than men. Women held a central position, taking on many roles such as planting and regulating relationships in the clan. Marriage in the matriarchal period was initiated by women, and children took their mothers’ last names, all demonstrating the important role women played in society.

In the feudal era, the introduction of Confucianism had a great influence on culture and society. Women in feudal society were dependent on the family and, specifically, men. Feudal society became a “pincer,” binding women’s rights and value to society.

In the modern era, under French colonial rule, gender inequality continued to thrive. The French colonialists chose women as the main object of labor exploitation; wages paid to hire female workers were much less than those paid to men. On the other hand, French colonialists also promoted the development of newspapers such as Nam Phong, Đông Dương tạp chí, báo Nữ giới chung, Phụ nữ tân văn, Phụ nữ thời đàm, and the Dong Kinh Nghia Thuc movement encouraged women to participate in lectures on history, literature, and politics. Vietnamese society also appeared to support early feminism, for example, Nguyen Thi Giang (Co Giang), Nguyen Thi Bac (Co Bac), Nguyen Thi Minh Khai, Nguyen Trung Nguyet, etc. These achievements have contributed to feminist thought in Vietnam.

Moving to the resistance period, the role of women was once again promoted. Women were forced to participate in the fight and defense of the Fatherland. The tradition of Vietnamese women, “when the enemy comes to their house, they also fight,” originated from the time of Ba Trung and Ba Trieu—women who rose up with the people to expel the Northern Vietnamese invaders. During the period from 1939 to 1945, with the strong development of the national liberation movement and the resistance war against the French, Vietnamese women in all parts of the country participated by devoting their youth and energy to work both behind the scenes and on the front lines. Across the country, millions of women joined the militia and guerrillas to fight the enemy using every means at their disposal. During the resistance war against the U.S. (1954 – 1975), Vietnamese women consistently proved to be an enthusiastic, courageous, and emotionally and creatively resourceful fighting force. The women’s movement further developed with the establishment of the Vietnam Women’s Union (October 3, 1946).

From the “Doi moi” (Renovation, carried out since 1986), period until now, women have become an important force and are represented in a large number of professions. The position of women has been strengthened. However, the issue of feminism has not been recognized by society writ large. Many people maintain a short-sighted view and false perception of feminism, causing the feminist movement in Vietnam to face certain difficulties. Researching and raising awareness of feminism will contribute to changing society’s perception of the current feminist movement.

Methodology

From the theoretical approach and objectives of the study, we apply the following research methods:

– Statistical method: We have collected a number of related works to provide relevant and specific arguments for the points to come to a final conclusion. The short stories by two female writers, Y Ban and Nguyen Ngoc Tu, represent contemporary Vietnamese short stories are consistent with the research content.

– Descriptive and analytical method: This method is used to clarify issues related to transfer patterns in each author’s work and analyze each author’s personal views on the issue. Gender discrimination is expressed through language. Thereby, clarifying the resistance of women to the issue of gender discrimination in contemporary short stories from the perspective of feminist stylistics.

– Comparative method: The use of a comparative method allows us to correlate research problems with the aim of finding similarities and differences between problems analyzed.

In this chapter, we delineate the scope of our research by focusing on surveying and analyzing transfer patterns in some short stories by two Vietnamese female writers, Y Ban and Nguyen Ngoc Tu, specifically:

– Y Ban: collection of 31 short stories from two collections of stories: I am đàn bà (I Am Woman) (published by the People’s Public Security Publishing House, 20006; republished by the Woman Publishing House, 2019); Truyện ngắn Y Ban (Y Ban’s Short Stories) (Publisher of the Writers’ Association, 1998; republished by the Writers’ Association Publishing House, 2020).

– Nguyen Ngoc Tu: collection of 32 stories from two collections of stories: Cánh đồng bất tận (The Endless Field) (Youth Publishing House, 2005; reprinted 2020); Khói trời lộng lẫy (Splendid Sky Smoke) (published by the Time Publishing House, 2010; reprinted by Youth Publishing House 2017, 2021).

Research Results

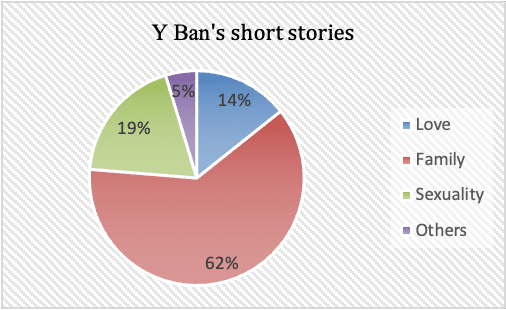

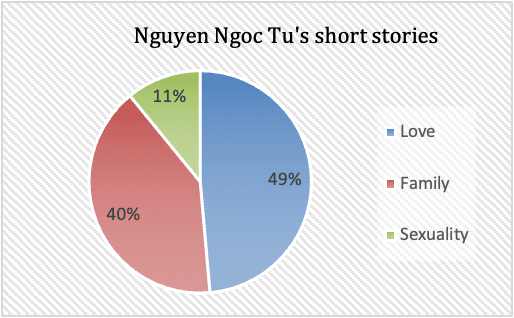

Conducting a survey of 32 short stories by Nguyen Ngoc Tu and 31 short stories by Y Ban, we observe that both authors mostly focus on themes related to family, love, and sexuality. Among these, the themes of love and family were predominant. In the case of Nguyen Ngoc Tu, all of 32 short stories revolved around three main topics: love, family, and sexuality, without the presence of any other themes.

Figure 6.1. Frequency of major themes in Y Ban’s short stories.

Figure 6.2. Frequency of major themes in Nguyen Ngoc Tu’s short stories.

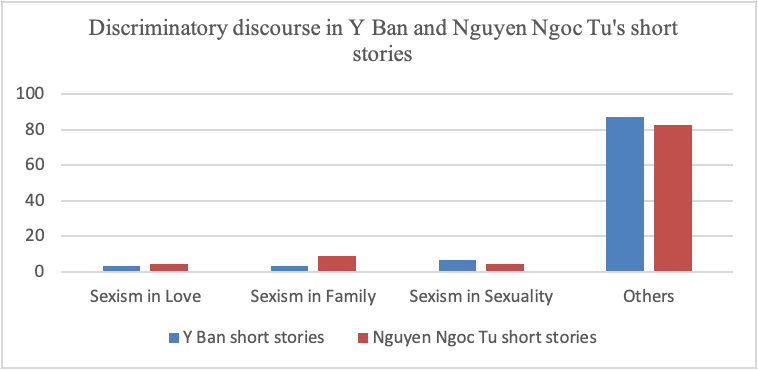

Investigating the statistical analysis on the frequency of discriminatory discourse and resistance of women against this issue in the short stories written by Y Ban and Nguyen Ngoc Tu, we can see the results as follows:

Figure 6.3. Frequency of discriminatory discourse in Y Ban’s and Nguyen Ngoc Tu’s short stories.

Although the frequency of discourse about gender discrimination appears infrequently, in terms of quality all three aspects of love, family, and sexuality are represented. In particular, the discourse on women’s resistance against gender discrimination on the family level is higher than the other two dimensions.

Understanding the resistance of women against the issue of discrimination expressed in the work, the survey’s results also show us that both authors reflect the resistance of women against the issue of gender discrimination all three aspects, namely, love, family, and sexuality, though the frequency of occurrence is still low.

Analyzing the adaptation patterns in some typical short stories by Vietnamese female authors, we have found how writers reflect the resistance against sexism in each aspect.

Results and Findings

Feminist Messages in Vietnamese Modern Female Authors

Women’s Resistance Against Gender Discrimination in Love as Reflected in Vietnamese Female Writers’ Short Stories

The feminist message in the works of Vietnamese modern female authors is expressed in two ways: one is the continuation of the spirit of fighting for women in literature, the other is the message against gender discrimination in the poetry of the two authors. The continuation of the spirit of fighting for women shows that modern Vietnamese female writers have continued to show an interest in feminism reflected in literature from the medieval period to the present. This began with the poet Ho Xuan Huong in the early nineteenth century to the early twentieth century with authors such as Nguyen Thi Manh Manh, Dam Phuong Nu Su, Suong Nguyet Anh, Nguyen Thi Minh Khai…until the contemporary period with authors such as Xuan Quynh, Du Thi Hoan, Doan Thi Lam Luyen, Y Nhi, Phan Thi Vang Anh…and the next generation, including Phan Huyen Thu, Nguyen Ngoc Tu, Vi Thuy Linh, Lu Thi Mai, Nguyen Thi Thuy Hanh, Ly Hoang Ly. Although an interest in what would become known as feminism was interrupted because of the war; in general, female authors have contributed to the feminist cause. Modern Vietnamese female authors received ideas about feminism from the previous generation and continued to develop these ideas. Female sexuality is especially represented in the work of contemporary Vietnamese female poets, greatly influencing the position of women in Vietnamese literature as well as the feminist movement.

From ancient times, love has been the eternal theme of literature and art. Among the rich and diverse topics of love, modern Vietnamese female writers have made readers feel the struggle against the gender discrimination in the context of love. Gender discrimination in this context has existed for a long time in Vietnamese society. Although society has changed a lot, this stigma has not completely disappeared. When it comes to gender discrimination, we want to mention the idea of “buffaloes go to find stakes, not stakes to find buffaloes” of ancient feudalism. This is a familiar Vietnamese idiom that employs a metaphor using the image of a buffalo and a stake to represent men and women. According to Vietnamese beliefs, men are seen as proactive, while women are viewed as passive. The metaphor draws on the characteristic of mobility (active position) for men and immobility (passive position) for women. Thus, men are implicitly compared to buffaloes, while women are likened to stakes. Consequently, in matters of love, only men are expected to take the initiative and confess their feelings, while women are discouraged from expressing their emotions.

Vietnamese culture is deeply rooted in wet rice agriculture. The imagery of a buffalo tethered to a stake, used by farmers to prevent the buffalo from wandering off, holds significant resonance in the Vietnamese psyche. It is from this agricultural context that the aforementioned idiom emerged. In this metaphor, men are symbolized by the buffalo, representing their perceived proactive nature, while women are likened to the stake, symbolizing their perceived passive role. This analogy draws directly from the agricultural practices familiar to Vietnamese people, further reinforcing its cultural significance.It is extremely common for men to have the right to take the initiative in love and at the same time push women into a passive position. While men usually take the initiative in expressing their feelings, women, bound by the rules of feudal rites, have to hide their true feelings and are usually in a passive position. Vietnam, having endured a lengthy period of colonization by China during the feudal era, was profoundly influenced by Chinese perspectives (Confucianism), including the doctrine of “Tam tòng” (Three Obediences) and “Tứ đức” (Four Virtues).

According to Confucianism, women are expected to adhere to the principles of Three Obediences, which dictate that they relinquish autonomy in decision making. These obligations include obedience to one’s father while still at home, obedience to one’s husband upon marriage, and obedience to one’s son in widowhood. In practical terms, this means that from childhood to adulthood, unmarried daughters are expected to obey their fathers, who have authority over decisions regarding their education, employment, and overall well-being. The mother’s role in decision-making is often secondary, as she, too, is subject to the authority of her husband. Consequently, daughters typically have limited agency in determining their own marriages or pursuit of personal happiness. The adherence to the Three Obediences dictates that upon marriage, a woman is integrated into her husband’s family, regardless of the circumstances, relinquishing any external support. Once married, she is expected to dutifully follow her husband, regardless of the joys or hardships she may encounter. In the event of her husband’s passing, she is then bound to follow the authority of her son, foregoing any possibility of remarriage.

Even in modern society, women’s initiative in expressing feelings is still controversial because many people still hold the view that “women are the weak sex.” Those with this view believe that in any situation, women should express only tenderness and modesty. Therefore, in their eyes, bold, proactive girls who confess their love first can easily be misunderstood as indecent. From there, they are perceived as easily taken advantage of or are underestimated as frivolous and indecent. As long as the above opinion is still held by the majority, sexism in love exists.

In Bồ công anh nở bên hồ nước trong (The Dandelion Blooms by the Clear Lake, 2020), Y Ban portrays her female character as free and actively seeking love like Nguyen Du’s Kieu:

Late night, the garden is late at night. myself: I went up the hill towards the log house. While groping for each step, I thought of the image of Kieu. It turns out that in every woman there is a Kieu. The key is still in the lock. I smiled to myself as I looked at the key that had been waiting for me all night. Its wait was not in vain. I gently unlocked the door. Very gently I entered the room. The room was warmly warm. I see him sleeping soundly in his small bed. (2020, p. 41)

By describing the female character’s active search for love, this Vietnamese female writer affirms that in the struggle for gender equality, women gradually gain confidence and take the initiative to liberate themselves. Women poets confirm women’s ability to be proactive in their thoughts and actions in their pursuit of sexual love. Breaking free from the dogma of the feudal rites of the “Three Obediences, Four Virtues” (2005) and social prejudices, this character no longer quietly waits for love in a passive manner. On the contrary, she boldly moves towards seeks happiness for herself.

Discourse on the issue of sexism in love as well as the struggle of women against discrimination is also mentioned by Nguyen Ngoc Tu but from a different perspective, in a quieter way through the view of the daughter character in the Dòng nhớ (Memorial Line, 2020). In Memorial Line, the daughter’s speech about her father:

Once upon a time, my father also loved a person. My father chose it himself. My grandmother definitely refused (grandmother had billions of reasons, but the biggest reason was that the woman had a husband), my father led people to run away from home, living a miserable life. The two of them went through so many hardships, such as harvesting, weeding, embanking…to get a few hats, my father bought a Koler machine to go to the fields to sell cotton. They live very poor. Every time the boat passed by, my father looked up anxiously, both remembering and hurting because of his father’s argument. (2020, p. 133)

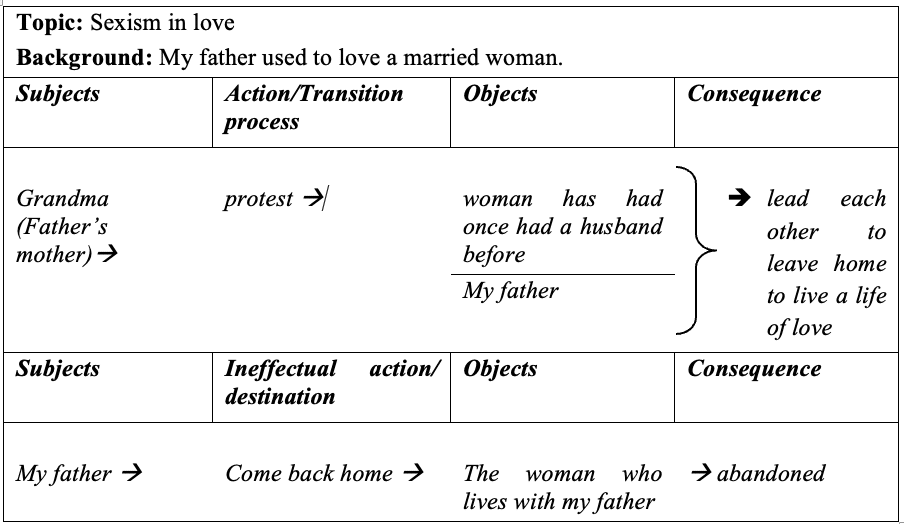

The daughter mentions one of the reasons why a relationship breaks up: the woman “has been married.” This reason often becomes the biggest barrier on the path to love for many women. Analyzing the point of view of the daughter’s character along with the “who did what to whom?” model, sexism and its consequences impact the abandoned woman in “Memorial Line” (2005). Just because that woman had once had a husband before, she was not accepted by the family of the person she loved: “Grandmother has billions of reasons, but the biggest reason is that that woman has had once had a husband before.” The “who did what to whom?” model shows us how the characters in the story affect each other. The transformation model of “Memorial Line” is as follows:

Table 6.1. Diagram of the transformation model of Memorial Line.

In the above model, we can see that the definitive refusal of the character “grandmother” in not allowing the character of “a married woman” to become a daughter-in-law in the family. “Grandmother” was also on the way back to her son: “My father led people to run away from home and live a miserable life.” Analyzing the character’s discourse according to the transfer model allows us to clearly see the consequences of the action of the character “grandmother.” At the same time, the character’s narration also clearly reveals the gender discrimination that Vietnamese society has against women. This paradox was even clearly defined in ancient feudal society: “A man with five wives and seven concubines / Girls who specialize in having only one husband” (Vietnamese proverb). So, while society does not object to men who have “five wives and seven concubines,” it is blatantly opposed to women’s love outside of marriage. Thus, the “woman of my father” in Memorial Line is a victim of this discrimination. Because of that stigma, even though the two characters “my father” and “my father’s woman” have a child together, their love is still not accepted. This stigma is finally brought to a tragic end: leaving the woman he loved and returning home to accept the marriage decided by his parents. But happiness does not exist in the marriage arranged by his parents. Characters often live in a state of insecurity as if they are in debt to someone:

It’s vaguely like I owe someone a debt, my whole family always feels unhappy, even though happy (these two things can’t go together). No one can claim it, but the debt is still a debt, it squirms around in the kitchen gable day in and day out, in the children’s beds, for two meals a day. Sitting around like that in the stomach thinking, there is someone lonely and helpless. But the worst thing is my grandfather, who was a lover of reformation, but whenever the TV shows a few plays with a cruel mother-in-law dividing the marriage of his daughter-in-law, my grandfather feels sad. (2020, p. 134)

Thus, Nguyen Ngoc Tu sends readers a heartbreaking message: gender discrimination has made love a tragedy, and it also disrupts the happiness of an established family.

In general, contemporary Vietnamese female writers show that women have gradually changed their perception of love. Most importantly, they portray a move toward liberation from social prejudices and fight against gender discrimination. At the same time, both writers also send the reader an important message: As long as society still discriminates against women, the struggle against discrimination will negatively impact lives.

Women’s Resistance Against Gender Discrimination as Reflected in Women’s Prose Works

The sexual barrier for women, first mentioned by Y Ban, was the strict standard of feudalism that did not allow women to get pregnant without being married. Women living during this period who were unmarried and pregnant were considered felons. Committing this crime, the girls would be scorned by society as “wild pregnant women.” More severely, in some villages pregnant girls were punished by cutting their hair or shaving their heads with lime, then tying their hands and feet to float in the river, leaving them to die. In 2017, the movie Thương nhớ ở ai (Love in Whom), directed by Luu Trong Ninh and based on the novel Bến không chồng (Ben Without a Husband), is set after the war and has haunted audiences just such a scene. It is clear that a woman cannot get pregnant alone, but she was the only person punished. This criminal has been given many bad names, “a humiliating person, a destroyer of fine customs.” Meanwhile, her accomplice in this crime did not suffer any punishment.

The short story Bức thư gửi mẹ Âu Cơ (Letter to Mother Au Co) by Y Ban (2020), although not reenacting the barbaric customs of the past, depicts a modern way of dealing with pregnancy that is also cruel. That is “the little girl is sixteen years old, she has just entered puberty and hastened to become a mother. She is a patient, a vaccine patient, she did not know she was carrying a germ in her body. The day before being brought to trial, she was still playing volleyball with her friends, sitting in a restrained position, occasionally getting up to relieve fatigue, and now she is lying there, recovering from the pain. 2020, p. 5). Letter to Mother Au Co calls the mother’s pain “the pain of having a spoiled child.” Just because of the premarital pregnancy, the mother was determined to take her child to have an abortion. No matter how much her daughter begged, the mother insisted on taking her to the hospital. Before she could absorb the pain of having to abort the pregnancy, the girl bent over to receive the contempt of those around her when she knew she was pregnant:

That day…

– The co-vac patient went to the medicine room. – The doctor’s voice called only for those who were awake.

The entire gynecology room got up and looked around in panic. Cossack is the sound of murder. From the bed in amazement, at the end of the room, I got up and prepared to go. All eyes turned to you, contemptuously:

– Oh, but I thought…

“But this morning, I was still talking to him her.”

– She looks like no one knows him, he’s gentle and kind, but she’s a bitch and a slut.

(2020, p. 6)

Y Ban describes the pain of a mother who didn’t protect her child: “After coming out of her terror, she suddenly understood what had just happened. She rolled her eyes. There it is—the baby is gasping for air. It doesn’t know how to cry yet, its eyes are wide open, its mouth is like two baby bird’s beaks that just yesterday she was still pinching her lips to feed a little saliva. And it lies there. The judgment is that it must die!” (2020, p. 5). So, the girl survived the co-vac process, but the pregnancy was terminated. Obviously, the sexual barrier that Y Ban wants to depict in the work does not stop at the girl’s physical pain during the abortion process, but it’s the mental pain of a young girl that is impactful. The culprit is none other than the prejudice and customs of society that deprive a young mother of her rights.

Y Ban also portrays another hidden corner of sexism in the extremely painful story of the character Mrs. Han, the widow in Goá ơi là goá (Widow is a Widow, 2020):

Cut the father of the widow is a widow. Widows can’t live to the fullest. When the eldest brother was still alive, every night and night came. Children are young. If you scream, the neighbors are far away, the children are close. They wake up, they laugh. I was afraid that I would wake up, so I had to go to the kitchen, pull the straw to cover my face, and let him do whatever he wanted. He is satisfied and tomorrow he steals his wife’s butter, peanut butter and rice to give. He also went to the garden to hoe the land to plant orange trees. That’s where the orange tree is growing, the oldest brother has planted 7 trees before, then chopped it again. Now the deaf guy has planted three more trees, not ten. The orange tree is so fresh, it’s blooming, it’s only tomorrow night and the next night it can’t find it, it will chop it to death. A widow is a widow. When the eldest brother was still alive, the sister-in-law never wanted to look at the face, and curse at the corners. At home, I don’t dare, I’m afraid of my husband, even my children know about it. Just go to the market to go to the fields and see, the sister-in-law will probably scold her face. (2020, p. 266)

Han’s confession to her niece reflects the painful and humiliating barrier that a woman has to endure: the widow who was sexually abused by her husband. The abuser is the eldest brother in the family. He took advantage of his sister-in-law’s situation as a widow, poor and sickly, and played a depraved game: “One night, I woke up early to go to the kitchen to cook bran. Waving his hands aimlessly, grabbing at the debt, stiffly resisting backwards. It turned out that it had come early to ambush me there. Oh, a widow is a widow. The army it steals, it doesn’t know how to love flowers and jade. It plays aggressively. It pinched for bruising. It bit the whole nipple off. A widow is a widow, she is in great pain, still dragging herself to the field in the morning. Mrs. Han sobbed” (2020, p. 268).

The sexual abuse taking place in the above story has shown the existence of a society where humanity is not for women. It is clear that Y Ban meant to use an unending timeline in the widow’s narrative. The meaning behind this phrase is to narrate a character’s life story, emphasizing the perpetual nature of their fate and the unceasing trauma associated with recounting their experience of rape. This approach aims to delve into the character’s psychology by illustrating the enduring impact of trauma. Perhaps she had to endure that pain every day, and no one knew exactly when the vile man would stop. Perhaps what Y Ban wants to depict is the unending physical and mental pain of the victim. The most heartbreaking thing is that the victim suffers in silence. If the eldest brother hadn’t died, Han would never have told this story to her granddaughter. Thus, Mrs. Han’s resistance is only expressed with her repeated lament: “A widow is a widow!”

Women’s Resistance Against Gender Discrimination in The Family as Reflected in the Work of Vietnamese Female Writers

It can be said that the sentiment “respect men and despise women” is still deeply rooted in the Vietnamese subconscious, reflected in the daily life of many families from the North to the South. Reflecting on gender discrimination in the family, Vietnamese female writers show how women protest such discrimination.

In Y Ban’s Con gái mang cuộc đời của mẹ (Daughter Carries Her Mother’s Life, 2020), the sexism is unfortunately reflected in the mother’s behavior towards her daughter. The mother did not love her daughter as she loved her son. The narrator’s character recounts a sad memory as a seven-year-old girl. At that age, she was often scolded and beaten by her mother for petty reasons, such as forgetting to boil water as her mother instructed: “In the summer, the whips really hit my skin” (2020, p. 323). It was only when she was deceitful that the little girl escaped her mother’s whip: “I just need to fill the kettle with rainwater and do not need to boil anything” (2020, p. 323). The girl was also not allowed to go out: “For a long time, my mother forgot about her vows; one afternoon she told me to make dinner early and let me go out. I’m happy, just carrying the tray and singing. Suddenly: Zhuang. Wow! I tripped over the door sill. Mom was furious again: Stay at home, don’t go anywhere. I begged my mother, but she still only took my two younger brothers. I cried loudly. It was getting dark, I suddenly felt so small and lonely” (2020, p. 323). Her younger brothers do not have to do housework and are not scolded by their mother. But because of their sister’s punishment, they have to stay at home. Because she was young, when facing her mother’s discrimination, she could only remember her father on the battlefield. While crying, she said: “Dad, come with me, I hate you so much. I just love them. No one loves me anymore” (2020, p. 323). The war ended, the father ended his military life, and the whole family moved to the city. Now, even though her living environment has changed, she still lives with her mother’s discrimination: “Going to the mother city is like different, my mother seems to be more comfortable. But for me, my mother is still strict. My mother followed my every step, my eating and sleeping habits, and then scolded me. I try to shrink myself into the word ‘ring’” (2020, p. 330). At this point, the girl began to think about how her mother treated her and her brothers differently: “For my two younger brothers, it was different, my mother pampered them much more than me. Mom used to hang out with them, which was strange to me. It’s a secret I can’t explain. Then I thought that my mother didn’t like me because I was a girl” (2020, p. 330). Those days of being discriminated against as a child are deeply ingrained in the narrator’s subconscious and impacted her feelings and actions later. Y Ban allowed the character’s resistance to develop from perception to behavior. The resistance at first only appeared in the girl’s mind: “When I told my father that I didn’t want to have a daughter, I didn’t want it to be like my fate, I burned it” (2020, p. 330). And that initial intention grew in the girl’s mind and became her fierce opposition to her mother: “Many times my mother just hinted—Daughter has time, get married or else. Every time my mother hinted at it, I became more and more stubborn in my thoughts—I will never give birth to a girl. Because of that drastic thought, even my body became more and more dry” (2020, p. 323). The girl’s resistance to her mother’s discrimination against her later impacted her actions. That’s when she avoided visiting her hometown with her family on a business trip away from home: “The next day, so that my father wouldn’t have a chance to tell me about the trip back home, I told my parents that I had to go on a business trip…It turned out that my trip was not a month but lasted for three months” (2020, p. 323). The character expresses her resistance by deliberately avoiding her mother whenever possible: “That’s why I never show affection with mom. There was even a time when mother and daughter entered the house together, I avoided going to the side so as not to touch my mother” (2020, p. 323). From the story of the little girl in Daughter Carries Her Mother’s Life we realize the very painful consequences of gender discrimination in the family.

Similarly, Nguyen Ngoc Tu also treats gender discrimination as well as a form of resistance against gender discrimination by women characters in two short stories Mộ gió (Tomb of the Wind) and Khói trời lộng lẫy (Splendid Sky Smoke, 2021). In the short story Tomb of the Wind, Nguyen Ngoc Tu discloses why the sister character in this work stays put and doesn’t get married. Sadly, the cause is sexism. The imposition of Asian society in the style of “the older sister must yield to the younger children” was enough to make it difficult for older sisters like this character. And the burden on the older sister’s shoulders is heavier when the younger child is a brother. Because the idea of “one boy means one, ten girls means none” is deeply rooted in Vietnamese minds. Parents always view their sons as important; meanwhile, girls, no matter how talented, are always in a secondary position and receive little attention from their parents. Therefore, daughters take care of all the important tasks for the family.

This is the situation of the two sisters in Tomb of the Wind. The older sister has to do many things by herself: “My mother gives me advice…Sweep the cobwebs on the altar with a straw broom…The house is finished; I walked back to the shop to buy and cook rice cake…There are still a few perch to store and pepper and beat their tails on the walls of the barrel” (2021, p. 56). While the older sister is so busy, the younger brother has only “running around and playing with dragonflies” to do. Her jobs, no matter how many, also include the responsibility of looking after her younger brother when her parents are not at home.

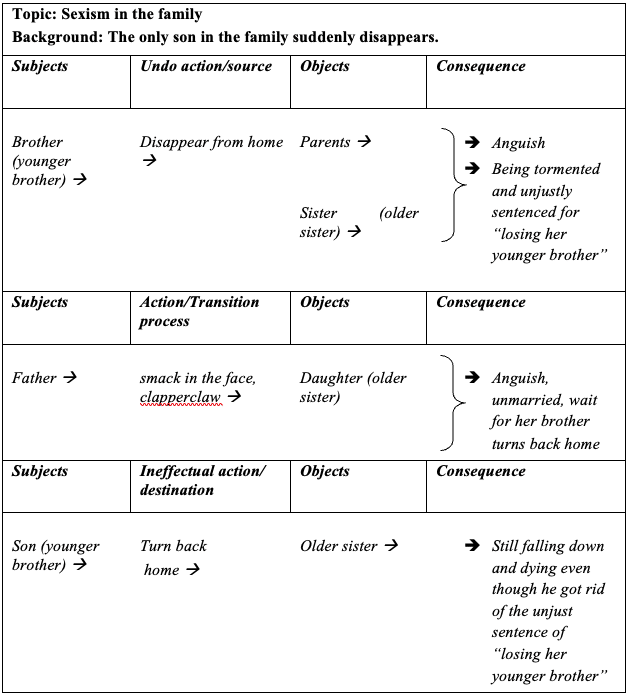

The model of transformation of the discourse Tomb of the Wind is shown as follows:

Table 6.2. Diagram of the transformation model of Tomb of the Wind.

The tragedy of the sister’s life began from the day her younger brother suddenly disappeared: “Many days later, when the neighborhood was in a mess because an eleven-year-old resident had disappeared, the sister still thought that her younger brother was playing somewhere. She was angry at those who expressed disappointment when they did not find the dead body, in the fields or at the bottom of the river. A puzzle with no answer, god damn it.” (2021, p. 57). Her younger brother went missing for no reason, but the sister was responsible for “losing the younger brother” and also suffered both the reproaches and the wrath of her parents: “Once, she forgot to set aside an extra cup, her father stuck her head in her ears, saying ‘I told you to watch over me’” (2021, p. 57). The parents’ condemnation of the older sister year after year is frustrating: “As if she was finished, and destined for every mistake, even though it is not very relevant, such as a mouse biting a pothole, and a fall of a papaya tree” (2021, p. 57). Since the day her brother disappeared, the older sister’s life is worse than death:

I live alone. Every time I was about to laugh, I suddenly remembered that I had lost my younger brother. Every time I’m about to marry someone, I remember in my mind being delirious and screaming, Vo, Vo. Every time I intend to live a human life, I remember that when I was dying, I would close my eyes forever. I buried her where in the morning I rolled up some rice paper money to the belt of my blue shorts, my gray shirt was smeared with banana latex, waved my hand, turned left, and rushed towards Mrs. Tu Mot’s grocery store. (2021, p. 58)

Ironically, after many years her missing brother returns home. Seeing her younger brother in the flesh, the older sister once again freezes: “I don’t know how I got home, flew, or crawled, or jumped into the trench over the water spinach. All I know is that Vo has to go back and fall down in front of the altar, to say: There, have you seen it, I told you that Vo was going out” (2021, p. 58).

Gender discrimination that takes place in the family is reflected by Nguyen Ngoc Tu’s Tomb of the Wind, a miniature version of Vietnamese society. Since her brother’s disappearance, the older sister bore a false accusation of “losing her brother” and after that she has to pay for this mistake with her whole life. Slowly, Nguyen Ngoc Tu makes the reader feel the suffocating pain of the character through the father because he is angry that the daughter has lost his only son. When the younger brother returns, he simply greets her with, “It’s me, Vo, sister!” This heartless brother did not know that he had pushed his only sister into a life of injustice, sadness, and loneliness. Nguyen Ngoc Tu describes the destructive power of gender discrimination when depicting the moment when the sister fell to her knees in front of her parents’ altar: “She knelt there for a long time, her hair disheveled to the ground, her back arched like a grave” (2021, p. 58). Unfortunately, the brother’s return was a final, fatal blow to his sister, leaving her completely devastated. The sister seemed to be buried alive again. When the character kneels in front of her parents’ altar and bitterly exclaims, “There, you see, I said Vo was going out!” (2021, p. 57). We see Nguyen Ngoc Tu’s depiction of the sister’s protest against gender discrimination. The story closes when Nguyen Ngoc Tu slowly and gently generalizes her message: “Men travel long distances, women struggle to sit at the door, life is so assigned” 2021, p. 57).

Similar to the older sister character in Tomb of the Wind, the character of Bay Trau and her half-sister in Splendid Smoke Sky is also the victim of gender discrimination taking place in the family. Once again, the idea of considering sons as more important than daughters is depicted by Nguyen Ngoc Tu in Splendid Smoke Sky. The idea of “respecting men and despising women” has been passed down from generation to generation and still exists. Nguyen Ngoc Tu confirms this inheritance when Bay Trau introduces readers to her father: “In his memory, he has no image, broken. I am not sad at all because of five daughters growing up with me sometimes their names are mixed up. He did not love his daughter, my grandparents did not love their daughter, they gave birth to a daughter to take care of him, let him ride, bully, and vent their anger. He was never the one to blame, for he was the only son of the famous rice merchant” (2021, p. 128).

And so, from this generation to the next, sexism only grows. Compared to Tomb of the Wind, the father’s discrimination in Splendid Smoky Sky is more severe and is reflected in more ways by writer Nguyen Ngoc Tu. In the past, the father character, who was “the only son of a famous rice merchant,” was pampered, but he also pampered his only son like that. As sparingly as he loves his five daughters, the generous father gives his endless love to his only son.

In the eyes of the father, there is only the existence of his son: “The day Phien was born, he pushed through all the fun games, all day he wandered around where Phien lay, swoon, ecstatically kissed, ecstatically said. All things the son looks like him, even the sneeze is the same” (2021, p. 129). As for the girls, he either coldly didn’t care about their existence or he saw them as a nuisance to him. The father did not realize that the staff member that the Research Institute sent to his house to do a thesis was his first daughter. This first child saw her father taking care of her younger brother and said with pity and regret: “I’m sure my grandmother will run out of land in the middle of the meal, or do it until then. She went to eat, then forgot about it. Must try harder, just attach a little bit of soil as small as a chili, I will become a boy. My father will stay. I will grow up in his arms. Like Phien Thuong’s father, he hugged him tightly, rubbed his face into his belly, his armpits, and deepened his red lips” (2021, p. 56). The father could not recognize his first daughter because he abandoned her mother when she was pregnant with her. But even a daughter named Trang—his child with his second wife—the daughter who lived with him since childhood was still hated by him, still being scolded and cursed by him all day long: “Twenty-four years old, Trang leads a pack of unmarried girls.” Her father saw it as a burden, and he dumped it on Trang. Every day he pokes his flat nose ‘like a dough ball thrown on a flat face,” and criticizes her smile as “useless.” He hates her curly hair “always as messy as a madman” (2021, p. 129).

In Splendid Sky Smoke, not only daughters but mothers are also victims of sexism. Bay Trau’s mother was abandoned by her father because the baby in her womb was not a boy as expected. As for Trang’s mother, after giving birth to a son for her husband, she was “happy because she wasn’t forced to give birth, didn’t have to walk to the birthing house by herself because she was pregnant with a female baby.” The story details are realistic because they are taken from real life. In many families, if a baby boy was born, the whole family is saved. Only after the birth of a son, can girls “be happy because they are not beaten and scolded for being girls” (2021, p. 129). It can be said that the cruelty of sexism reaches the highest level when Nguyen Ngoc Tu compares the father’s attitudes toward the children. Even though his daughter disappeared the night before, the next day he “still calmly urged his wife to cook sticky rice and tea, calmly carried the little boy Phien was in the hammock, relieved as if he had just lost a chicken or lose a game of cards” (2021, p. 130). It is clear that the existence of daughters was not in this father’s interest. But when the only son disappeared, the father’’s tears “swept on the newspaper” and in the father’s only statement to the reporter, the son was his everything: “I just need the boy, I will exchange with all my inheritance, my life” (2021, p. 139).

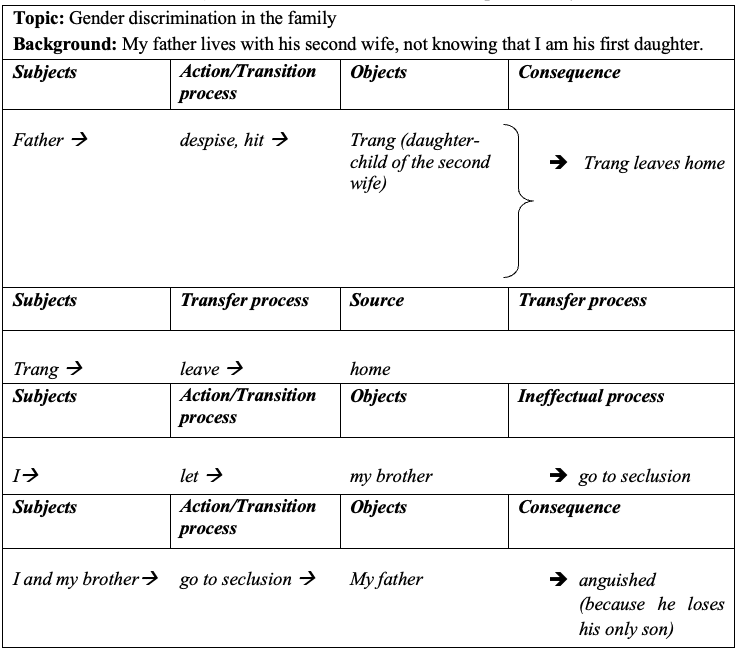

The transformation model of the Splendid Sky Smoke is shown as follows:

Table 6.3. Diagram of the transformation model of Splendid Sky Smoke.

Unlike the sister character in “Tomb of the Wind,” both Trang and Bay Trau in Splendid Sky Smoke protest gender discrimination. Trang’s protest is to leave home on the night of preparing to leave the youngest brother. Bay Trau did not leave alone. Instead, she takes her younger brother, her father’s only son, and quietly disappears: “One day I sent all the machines, the samples I had to the Institute by post, and the samples I had, raw unprocessed, filtered audio. Mixed in, there must have been a mosquito smacking sound, and I said, ‘So sad, I’m holding Phien to go out.’ Nature punishes man by disappearing, I have never forgotten, you said that. I also began the journey of disappearing, with Phien” (2021, p. 131). Trang and Bay Trau leave the country because they could no longer tolerate their father’s discrimination against them. When they realize they have no value in the eyes of their father, they decide to leave. Unfortunately, this does not free them from stigma, but, on the contrary, brings them painful consequences. Leaving like that, they begin a lonely life full of alienation. It can be said that Bay Trau’s resistance is also her father’s punishment: the son he loved the most did not say goodbye. Thus, Trang and Bay Trau’s level of resistance against gender discrimination is more drastic than that of the unnamed sister in Tomb of the Wind.

Overall, both Y Ban and Nguyen Ngoc Tu confirm that gender discrimination still exists in modern Vietnamese society and that women in Vietnam are resilient. The writers convey criticize sexism through their characters. More importantly, by sending readers a message against gender discrimination, both Y Ban and Nguyen Ngoc Tu have sounded the alarm to parents about the destructive cruelty of gender discrimination.

A Message About Vietnamese Women’s Desire for Happiness

Desire for Happiness Love

The days when Vietnamese women were so bound by feudal customs that they could not have freedom in love and marriage are mostly in the past. Experiencing the struggle for gender equality, women have attempted to ridthemselves of old-fashioned ideas, such as “children have to do what parents want” or “only men look for love, and women should not.” Women’s initiative to change their fate is clearly affirmed by these contemporary literary works. Reading the short stories of the two writers, we encounter many female characters with new self-images. The female characters are bolder when expressing their desire for happiness and are more active in their own love affairs than older characters.

Nguyen Ngoc Tu describes the emotions of the two grandparents in Rượu trắng (White Wine, 2021), where a grandmother and granddaughter live together in a house without a man. The portrayal of the grandmother through the innocent eyes of her grandchild, creates a vivid portrait of a woman full of love. That beautiful portrait is the result of a love returned. The grandmother could not hide the happiness of a woman in love (smiling, eyes sparkling with sunlight). To express the emotions of a woman in love, Nguyen Ngoc Tu vividly conveys the grandmother’s character, preparing meals for the character Bien. The grandmother expressed her love for Bien in the simplest ways (saving chicken legs, preparing lemongrass melons, bringing soup with snakehead fish head to the table), and that expression helped the grandmother replaced the love she wanted to express to Mr. Bien. The loneliness of the grandmother with her little granddaughter seemed to be dispelled thanks to the happiness that Uncle Bien brought to her because “those signals of love she let loose were caught and answered; it makes her happy” (2021, p. 79). In telling readers the love story of the grandmother, Nguyen Ngoc Tu sends a message: every woman has the desire to love and be loved.

Nguyen Ngoc Tu also shows the novelty of women’s thoughts in the way they take the initiative in deciding to put an end to a love. Instead of crying, mourning, or lamenting, they decide to let go, not hate. Be in “There Is a Ship Leaving the Shore” is one such a character. At first, Nguyen Ngoc Tu describes her with the following: “She kept a few secrets in her heart, apart from the fact that everyone knew: thirty-two years old, her house was in Lang Chao dam, far from the city. This street takes four hours by boat and half an hour in foot. Unmarried, seems to hate men” (2021, p. 31). Later, Nguyen Ngoc Tu reveals to readers a little more about the character Be. It turned out that she had once suffered from the pain of an unfaithful lover. He left her and married someone else. And Be was forced to put aside the desire for love. What is worth mentioning here is the way that Be stood up after her heartbreak. The character did not let the failure of love defeat her. When the painful moments passed, Be boldly took the initiative to meet him, not resume their relationship, and to let go.

Desire for Familial Happiness

Both Y Ban and Nguyen Ngoc Tu express a woman’s aspiration for familial happiness in material and spiritual terms. The character depicted in I am đàn bà (I Am Woman, 2019) hard to earn money for her family. As a sincere and honest woman, though poor woman, she sees a baby abandoned in the forest and decides to take him home. She takes him to care for him and raise him, although having an extra mouth to feed is an economic hardship for her family: “One more meal, but the town house was not allowed to share any more land. The chairman of the commune said: ‘If you can’t raise it, you can take it to the forest and pay for the trees, but where else can you take the land to divide it for your family. People can give birth, but the land cannot give birth’” (2019, p. 123). She and her husband do not hate the boy because of this. The boy is loved because he is the youngest.

It is clear that she and her husband are better than other poor people in the story because of their kindness. Describing her family’s situation more carefully, Y Ban writes: “She and her husband are famous in the village. On the land of her house, there are always trees growing, but the soil is too barren. That’s just enough for the mouth. The children are growing up and eat fences like silkworms. All day long, working hard on the land to find food without knowing that people have changed so much” (2019, p. 123). It was this living situation that made her decide to work abroad. She believes that if she works hard, her family will have a little more money and her husband and children will be less miserable:

When Duc turned five, the village she lived in had a big change. That’s the kind of woman who has been around the kitchen for so long, suddenly going abroad to do business. Watching people in the village see each other off on the plane, then take each other to the post office to receive money. If you have money, build a house and buy a TV. She and her husband are sometimes invited to dinner parties. At night, husband and wife lying together also have dreams. Dreaming of a morning, Lang is allowed to labor export. Their daughter lives with her parents who are so poor; they dream of her suffering a little less. As for Nhan and Duc, it’s okay, it’s okay to stay in the countryside and plow the fields. (2019, p. 124)

Describing Thi’s intention to work abroad, Y Ban introduces a change in women’s lives in Vietnam. No longer in the position of “woman building a nest,” women today are in a more active position. They work outside the home to earn money to support their families. Their support is valuable not only spiritually but materially.

Many female characters in the story of Y Ban and Nguyen Ngoc Tu are lonely. An example of this loneliness offered in Y Ban’s Sự nhầm lẫn bò cái (Cow Confusion, 2019). In this story, Y Ban portrays the wife through the lens of her husband: “He mistakenly married a wife who did not know how to cuddle. She is just a smart and well-mannered woman. In the time when rice was mixed with cinnamon, the surrounding houses were full of hunger, but his family still had enough rice and fish to eat. Two smart and obedient children. They are always at the top. Having a wife ensures he doesn’t have to worry about family matters. He is focused on work. He became a good man at work. Sales cannot be without experts like him. He has a lot of money. He gave it to his wife. The wife, like him, is very good at work, but she is hard on herself. How much money her husband gave her did not…[inspire her to] make every effort…to keep her rich husband; a rich husband is an open-air gold mine. His wife took his money to invest in land. Good luck, wife, buy whichever piece wins, double or triple. Money entered his house like a flood”(2019, p. 155). When it comes to his wife, the husband uses the word “she,” a name that does not help him to express the affection he should have for his clever and skillful wife. Every advantage of the wife becomes a weakness in the eyes of the husband. This husband does not know how to appreciate his wife. His comment, “She’s just a smart and well-behaved woman” reveals his contempt for his wife. And when takes a lover: “It all came crashing down when a young woman demanded a family meeting to publicize her pregnancy as the son of her brother-in-law. At that time, he kept lurking in his head, not knowing if there was a mistake, making love at first sight, how did she get pregnant. His wife had a quarrel, and then helped him. To preserve his official position and his reputation, his wife bought her a comfortable house and [got her] a stable job. And gave her a husband. When the baby was born, his wife quietly went for a DNA test, the result was that it was not his child” (2019, p. 157). Y Ban’s narrative voice shows us the husband’s harsh attitude, looking down on his good wife. The wife is very tolerant of her husband’s mistakes, including adultery. But the dream of a family with a husband who truly loves and understands her is still just a dream. Although she has entered the marriage with her husband, she is alone in her life.

Like Y Ban, Nguyen Ngoc Tu also portrays female characters whose desire to be loved is always burning in their hearts. We found that there is a similarity between the character of the wife in Nguyen Ngoc Tu’s Thềm nắng sau lưng (The Sun’s Backside, 2021) and the character of the wife in Y Ban’s Confusion of Cows (2019). Married to a heartless husband, the wife in the The Sunshine Backside cries over many times over her husband’s actions. Once her husband drops their son without realizing it: “By just hearing about it, even the case of his father carrying him out to play in the neighborhood, coming home in his arms with a few sheets of cloth wrapped around him, and he fell into a pile of straw by the side of the road. Only four months old, Bang has no memory, so he can’t remember how he was in pain and crying, so he can’t be mad at him for that negligent crime” (2021, p. 66). Another time, the husband makes his wife angry because he was more interested in playing with his friends than caring for his family: “The next day, the three boys tied the boat to the docks, their faces and clothes were rumpled. He drove ten bushels of rice to the mill, met a friend passing by, invited him to go to the market to drink and play, he nodded. At the market he met a few more friends, they asked to stay tomorrow, he nodded again. When they returned to the empty boat, the three boys sold rice and spent all their money playing. Bang’s mother lay face to face against the wall, her eyes wide open, but tears kept flowing. He tiptoed on the wet and squashed floor, pulled his son’s hand, come on, let’s go to the garden to play” (2021, p. 67). Nguyen Ngoc Tu’s story is just a typical example of the family world where many women are forced to take care of everything to keep the house in order. But like the husband character in Y Ban’s Cow Confusion, the husband in Nguyen Ngoc Tu’s Backside of the Sun falls in love with another woman and leaves home. In a jovial but cold and painful voice, Nguyen Ngoc Tu depicts her husband’s return half a year later. He was just “visiting the house” and behaved like a guest, his son treating his father as a guest.

Nguyen Ngoc Tu does not write much about characters’ inner life, so the characters’ thoughts are a bit of a mystery to us, only revealing, “Two or three children sitting on the sidewalk, his mother was coldly swimming around her grandmother, probably crying over there. That day, your father had been away from home for almost half a year” (2021, p. 68). Thus, the only resistance of the wife in this story to her husband’s betrayal is tears and just to “walk away.” Even though these female characters live and die for their families, happiness is still far from their reach.

Desire for Sexual Happiness

Discussing sexual elements in literary works, Y Ban writes:

There is nothing strange to man that is strange to literature. This is a necessary matter because literature was born to serve people. In other countries, especially Western countries, they see sex very frankly and openly. And when movies didn’t exist, literature would convey this. Literature is also the most enduring and profound path. Films, paintings, sculptures…only convey certain aspects of sex, while literature conveys all, distilling a lot of interesting things.

Looking at sex in the short stories of Y Ban and Nguyen Ngoc Tu, we found both writers express women’s feelings. In her short stories, Y Ban first writes about women who express their natural human instincts when it comes to sex: the desire to love and to fulfill their own sexual needs. A typical example is the character in I Am Woman (2019). The character Thi chose to stay away from her husband and children, leaving her homeland to go to Korea to work as a maid. Wanting to earn a little more money to feed her family, she worked extremely hard in healthcare (with stroke victims). She also accepts work from her landlady, which changes her peaceful life.

In the end, her lust triumphed over reason. Thi dreamed of going into her boss’s room, looking deeply into those happy eyes. Then she took off her clothes, turned the thin towel over her boss, and like her dream, she took his penis and put it inside her. Thi didn’t have to wake up in a burning lust anymore; she was satisfied.

A woman’s sexual desire used to be a very secret affair. To be virtuous, a woman had to hide all sexual desire. Because Thi didn’t want to be called a “slut,” she didn’t reveal her true thoughts and feelings when it came to sex. When she takes the initiative in sex, confidently and frankly expressing her very human sexual desire, Y Ban’s character promotes women’s self-assertion and affirms their self-worth.

In addition to openly expressing their desire for sexual satisfaction, the female characters of Y Ban and Nguyen Ngoc Tu also voice a desire to free themselves from dependence on men. In The Dandelion Blooms by a Clear Lake (2020), the desire to be independent of men in terms of sex is mentioned in a new light by Y Ban’s character:

If in nostalgia is simply sex, you will have many ways to relieve it. All you have to do is pick up the phone. Not a single man turned down such an offer. The simpler way is a tool. Science has not proven that it is very effective without being unethical. Since it’s just you and you and an inanimate device, no one would pry. (2020, p. 43)

So, sex toys are discussed openly in Y Ban’s Dandelion Blooming by a Clear Lake. Maybe this is the message the writer wants to send to those who still associate sexual control with morality and think that not having control over your own sexuality is vile. Y Ban considers it normal for women to use sex toys, asserting that there is nothing to condemn or be ashamed of because the need for sex is instinctive, and it is natural to find ways to address that need. Y Ban and Nguyen Ngoc Tu have helped women openly express their views on sexuality.

In addition to messages about love, family, and sex, the works of these modern Vietnamese female writers reveal a sense of self. First-person pronouns often appear in their compositions. It is an independent “I,” wanting to express definitively how to see and evaluate problems. In the works of these Vietnamese writers, each time the “I” appears, it has a different tone: expressing an earnest voice full of aspiration and contemplation. Young writers today are the voices of affirmation of aspiration.

Conclusion

Using the analytical model of Feminist Style theory, we have surveyed the works of some contemporary Vietnamese female writers. The results show that discrimination against women is still a part of daily life in Vietnam in aspects of love, family, and sex. The obtained results also clearly reflect the impact of gender discrimination on women in particular and on society in general. At the same time, we also found specific ways that women fight sexism, conveying messages about sexism in contemporary Vietnamese writing and criticizing sexism. Based on our findings, we can see that a contribution to awareness in society about feminism and equality has been made.

References

Arweesh, D. D., & Ghayadh, H. H. (2018). Investigating feminist tendency in Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale in terms of Sara Mills’ model. A feminist stylistic study. International Journal of English Language Teaching, 6(7), 17–30. https://www.eajournals.org

Beauvoir, S. D. (1949). The Second Sex. https://www.academia.edu

Burkett, E. (2021). The Second Wave of Feminism. https://www.britannica.com

Burton, D. (1982). Through glass darkly: Through dark glasses. In R. Carter, ed. Language and

Literature. An Introductory Reader in Stylistics. London: George Allen and Unwin, 195–214.

Brunell, L., & the Editors of Encyclopedia Britannica. (2021). The Third Wave of Feminism. https://www.britannica.com

Encyclopedia Britannica. (2021). The Fourth Wave of Feminism. https://www.britannica.com

The Guardian. (2012). Doris Lessing’s Golden Notebook, 50 years on. https://www.theguardian.com

History.com. (2022). Feminism. https://www.history.com

Hiatt, M. P. (1977). The Way Women Write. https://archive.org

Mills, S. (1995, 2005). Feminist Stylistics. London & New York: Routledge.

Montoro, R. (2014). Feminist Stylistics. London & New York: Routledge.

Rahimnouri, Z., & Ghandehariun, A. (2020). A feminist stylistic analysis of Doris Lessing’s The Fifth Child. Journal of Language and Literature, 20(2), 221–230. https://e-journal.usd.ac.id

Ryder, M. E. (1999). Smoke and mirrors. Event patterns in the discourse structure of a romance novel. Journal of Pragmatics, 31(8), 1067–1080.

Showalter, E. (1985). The New Feminist Criticism: Essays on Women, Literature and Theory. New York: Pantheon Books.

Siregar, S. F., Setia, E., & Marulafau, S. (2020). A feminist stylistics analysis in Rupi Kaur’s The Sun and Her Flowers. Journal of Language, 2(2), 170-186.

Sunderland, J. (2006). Language and Gender. London & New York: Routledge.

Wollstonecraft, M. (1792). A Vindication of the Rights of Women. www.earlymoderntexts.com

Wulandari, S. (2018). A Feminist Stylistic Analysis in Laurie Halse Anderson’s Novel Speak (Sarjana Sastra: thesis). University of Sumatera Utara, Medan.

Survey data

Y Ban. (2020).

Truyện ngắn Y Ban (Y Ban’s Short Stories). Writers’ Association Publishing House: Hanoi.Y Ban. (2019). I am đàn bà (I am a Woman). Women’s Publishing House: Hanoi.

Nguyen Ngoc Tu. (2020).

Cánh đồng bất tận (The Endless Field). Youth Publishing House: Ho Chi Minh City.Nguyen Ngoc Tu. (2021).

Khói trời lộng lẫy (The Splendid Smoke Sky). Youth Publishing House: Ho Chi Minh City.

Comments